This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

When developers came up with the Espresso Book Machine, they probably didn't have artists like John Andrews in mind.

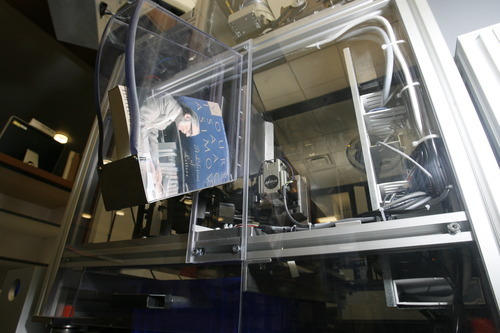

It's not that the engineers weren't pushing technology's cutting edge or hadn't set their sights high enough. After all, they developed the Espresso, commonly referred to as the EBM, to be publishing's future. The contraption, which takes up less space than a Mini Cooper, is basically a literature vending machine.

A customer with a hankering for Jane Eyre, for instance, or A History of Daggett County from the University of Utah's special collections, downloads a digital file from the Web and in about 15 minutes, Espresso prints, binds and trims a fresh copy. Cost: $10.

Or you can download a digital copy of a new paperback in print from many publishers, including Simon & Schuster, WW Norton or McGraw-Hill (some publishers still are reluctant to venture into the digital era). Espresso will spit it out for the same price as in the bookstore.

But the most intriguing use of Espresso is as a way for authors and poets to publish and print their own literature at little more than the cost of the paper. (Imagine how many trees will be saved when self-published novelists give up after printing only 10 copies, rather the usual several hundred or thousand from a vanity press.)

Taking the gloves off • But visual artists like Andrews, who graduated in fine art last year, are taking the EBM in the University of Utah's Marriott Library a step further by "subverting" its technology to mass-produce conceptual art.

Of course, book-as-art is nothing new, especially if you include hand-illuminated medieval manuscripts under the definition. So-called artist's books tend to be handmade in limited quantities.

But in the 1960s, artists, including Lawrence Weiner, took artists' books into the conceptual-art realm through mass-production methods that made them affordable and even disposable, Andrews says.

"I don't like the idea of putting on white gloves to look at an art book," he says. "It's inhibiting. It's a barrier to the art."

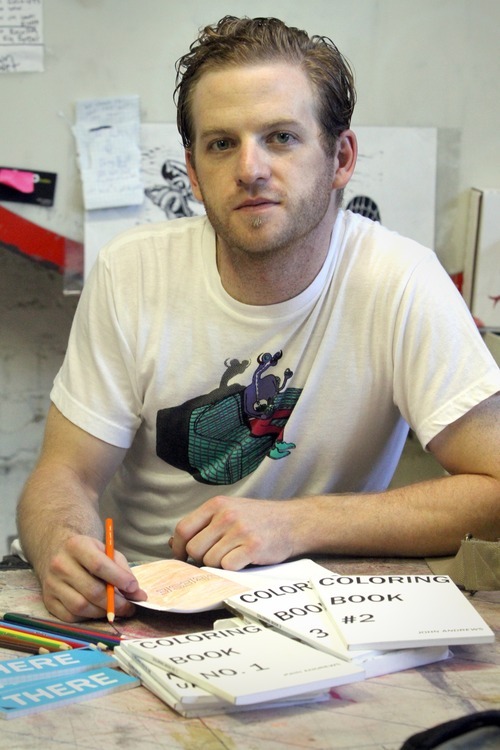

Using EBM, Andrews produced a trilogy of Coloring Books that serve, he says, as conceptual-art workbooks. Each page presents a word and asks the reader to respond artistically to whatever the word evokes. The books start with "carrot," but soon ask the reader to color or illustrate more compelling words like "grave."

"I'm telling people to grab art materials and make something. I like art that isn't complete until it's acted upon," Andrews says, flipping through one of his EBM-produced books. "It's clean and feels like it's 'official.' But you could use these books as coasters and not feel bad."

Andrews sells his coloring books at art walks and at gallery shows for about $10. "Art should be everyday and in your face and affordable — like a DVD."

ATM for books • Ian Godfrey, the Marriott's integrated library systems and operations administrator and lord of the book machine, says most of the $90,000 Espresso Publishing Machines, described as an "ATM for books," are found in bookstores. As a library, the Marriott is looking for ways to reach potential users and increase use of the EBM, which, right now, prints about 38 books a week, Godfrey says. "We are aggressively moving to produce content to users in a timely fashion."

Some of the innovative uses, so far, include a literature professor printing for his class 18th-century books that would otherwise have been unavailable or extremely expensive. Other scholars have printed copies of fragile volumes from the Marriott's rare book collection.

"We can scan a book in less than an hour and Espresso will give you a copy you can take with you that you can annotate," says Godfrey.

Last year, the Salt Lake Library used the Espresso to publish journals of text created by schoolchildren during an Anne Frank exhibition.

It's the area of self-published books that intrigues Godfrey. Self-publishing — everything from thesis papers to art books and blank journals — is the biggest use of the EBM, he says, followed by public-domain titles.

Hijacking the machine • David Wolske, creative director at the U. of U.'s Book Arts Program, has been encouraging art students like Andrews to embrace the book machine and push its limits. Andrews says book-arts instructors encouraged the students to "hijack the machine."

The EBM, which is really a series of bookmaking robots in a box, clamps and manipulates the pages to glue and bind the books. It can cut them to any size between 8 1/2 by 11 inches to 4 1/2 inches square.

In one instance, Wolske wanted to use a book cover that he had printed with his collection of wood type, instead of an image produced by the EBM's color ink-jet printer. Because the software didn't offer an option for home-brewed covers, he had to fool the machine into thinking it was printing a blank page as he fed his hand-printed cover into the binding-and-cutting steps. Though the current generation of Espresso can only print illustrations and charts in black-and-white or gray scale, work-arounds like Wolske's could allow subversive artists to insert color illustrations.

"I'm personally very interested in how to take advantage of new technologies and find ways to subvert them," Wolske says. "I'm pretty sure the makers of this machine didn't envision it being used for art books."

As artists around the country are experimenting in similar ways to produce artists' books, later versions of EBM may become more artist-friendly and even include color printing beyond the cover.

"That would be cool," says Andrews. "But expensive."

Still, a final question remains: Why do readers need Espresso at all? In a digital age, in which we can download millions of titles to our e-readers from online databases, EPM, even with all its robotics, is still a throwback to Gutenberg.

Godfrey admits returning digital data to paper-and-ink books seems counter-intuitive, but argues, "There's something about holding the physical object. The artifact appeals to people."

Conceptual art, which some might argue doesn't need even to be produced as an actual work, further muddies the need for physical books.

Andrews agrees to some extent with that idea, but says, "That people want books is a testament to the need for the physical object. I still like physical objects that come made."

facebook.com/tribremix —

More about the Marriott's book machine

Basics of the Espresso Book Machine

Setup cost • $25 (including a full-color cover)

Cost per page • 5 cents. If you provide your own paper, it's 4 cents.

Printing time • 15 minutes

Bonus • The machine backs up and preserves your digital manuscript. —

Publishing with the 'book ATM'

1 • Reader chooses a digital file from online book database or provides text.

2 • Espresso requires two .pdf files: one each for the text and full-color cover.

3 • A laser printer prints text. A color ink-jet printer produces the cover.

4 • Espresso collects the pages and color and aligns them.

5 • The machine glues the pages to the spine of the cover.

6 • A carbide blade cuts the book to the proper size.

7 • The completed book is ejected to the reader in about 15 minutes.

You can watch here • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q946sfGLxm4