This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

South Jordan • Even the most basic punctuation problems spell trouble for Jessica McGrath.

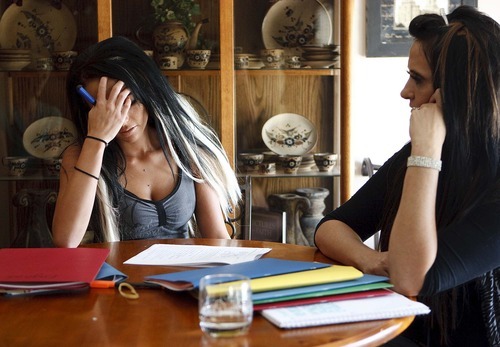

Sitting at her kitchen table, the 17-year-old frequently closes her eyes to the work of capitalizing proper names. The words won't sit still on the page. She says parts of her brain feel "paralyzed," and she covers her face with her hand.

Then she pulls out a pocketknife to cut a prescribed pill that will help her focus. Talking about the blade, decorated with gray flames, finally animates her monotonous voice.

The weapon gives her a tangible sense of control, which she doesn't have when she feels flashes of anger and bouts of helplessness, when she can't sleep or has nightmares reliving her peers yelling, "Kill her!"

McGrath is not a returning veteran or a refugee from war. But she has post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

So do nearly 11 percent of the children in Utah's public mental-health system, or about 1,700 kids and teens, according to data requested by The Salt Lake Tribune.

In Salt Lake County's system, more children were diagnosed with PTSD last year than much better-known autism spectrum disorders. And one third of the 250 to 300 abused children seen in Primary Children's Medical Center therapy program — many of whom have private insurance —have PTSD.

It is not known why so many children are suffering. And because the disorder is difficult to diagnose in children, the numbers could be higher.

PTSD can be triggered when a child endures physical, sexual and emotional abuse or neglect, or witnesses violence. The unexpected death of a loved one, dog bites and serious illnesses also can cause prolonged distress.

"People don't understand how much trauma is going on," says Douglas Goldsmith, executive director of The Children's Center in Salt Lake City and Kearns, which provides mental health care to children up to age 8. "We really, really don't want to believe that bad things can happen to kids."

But even as their ranks are growing, children now have better therapies to help them recover. In short, they need to tell their stories.

—

Persistent memories of pain • As a plump eighth-grader, Jessica heard classmates "moo" at her and shout slurs about her dark skin in the halls of West Jordan Middle School, she says.

The bullying culminated on a Wednesday in May 2008, when a girl, whom Jessica would later tell police had been "tormenting" her for weeks, got off at the same bus stop. Up to 30 students followed to watch the planned fight.

"Everyone's around us, and she just started pounding my head. I don't really remember the fight after that," Jessica recalled recently.

A police report says someone in the crowd videotaped the fight and the crowd yelling "kill her" and "kick her ass." The Fire Department was called to treat Jessica; the other girl was unharmed. Jessica was eventually diagnosed with nystagmus, a brain injury that causes her eyes to dance around, her family says.

The fight happened more than three years ago, but in Jessica's mind, it's stuck on replay.

Mental health experts once thought that children soon forgot their pain. But it's now considered well-established that children do suffer from PTSD.

Most children and adults who experience trauma — a life-threatening event that a person sees or experiences — are resilient and won't develop the disorder. But for those who do, their initial reactions of horror, helplessness or terror persist.

The trauma can stay in a child's mind in nightmares or flashbacks. Children may try to avoid anything that could be a reminder. And their bodies "stay on alert" — they struggle to sleep or concentrate, are irritable, angry or startle easily, according to the National Children Traumatic Stress Network. For a PTSD diagnosis, the problems must last more than a month.

The symptoms can disrupt children's emotional, social and even brain development.

Children may suffer more when their parents don't believe they were abused, or when parents think they are too damaged to recover.

Rene J. Valles, Jessica's psychiatrist at Valley Mental Health, likens it to a toddler who falls. One parent claps at the effort and laughs — and the child does the same. When another parent anxiously runs forward, the toddler "might not be hurt, but they see the way the parents react and it frightens them."

—

'It kills me inside' • For Jessica, PTSD looks like this: She can barely sleep, and when she does, she often has nightmares about the fight. She can be easily angered. She kept a knife under her bed after the fight, afraid the girl would come to kill her. Being in large crowds, like at the Dew Tour this summer, take her back to being surrounded by classmates as she was punched in the head.

The once college-bound girl — whose sixth grade teacher predicted on a report card that she could "accomplish anything she wants" — can't imagine her future.

For years she refused to talk about her feelings. Her journal entries from last December chronicle how numb she had become — another key symptom of PTSD.

"I wake up every day wishing I hadn't woken up at all. It kills me inside knowing that my life has been taken. My days are spent in bed, crying, just wishing I could be OK again. …"

Jessica's mother, Joni Draper, reads the entries in their South Jordan kitchen with Jessica's permission. It was that severe depression — Joni used to stay awake at night to make sure Jessica wouldn't follow through on her suicidal thoughts — that led the family to seek help at Valley Mental Health this past summer.

"My whole personality changed after the fight. I didn't care about who I hurt or what I did pretty much because I didn't care about my life," Jessica says.

Valles says worried parents don't ask about PTSD. They describe depression, aggression, anxiety or problems with school or friends. Young children may regress — sucking their thumbs or wetting the bed. They might show new anxiety about separating from a parent or a new fear of the dark.

If parents or patients don't reveal a trauma — they may not know or may be ashamed — children can be misdiagnosed with attention deficit disorder, depression, bipolar or other disorders and could receive ineffective treatment.

"Unfortunately, we can't draw a blood level or take an X-ray," Valles says.

—

Children at risk • Clinicians can't say why more Utah children are being diagnosed. Talk about PTSD affecting returning veterans may have raised awareness. With diagnostic tools now easier to use, primary care doctors may recognize mental illness more often and refer children to treatment. Utah's growing population of refugee families — fleeing war or torture — may account for part of the increase.

Poverty and stress are considered risk factors for abuse, leading to speculation that the recession and lingering unemployment could lead to the type of violence linked to PTSD.

Researchers found a significant increase in children under age 5 who suffered abusive head trauma during the recession in counties they studied in Washington, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kentucky, according to a study published in September in the journal Pediatrics.

Nationally, so many children are being exposed to trauma that the American Psychiatric Association has proposed adding a PTSD diagnosis for preschool-aged children, taking into account how they may re-enact the trauma through play or may show hyperarousal through extreme temper tantrums.

Utah data on abuse are less clear-cut.

The reported numbers of children who were physically or sexually abused or saw domestic violence dropped in fiscal 2011 to the lowest levels seen in at least five years, according to the Division of Child and Family Services. While DCFS leaders hope it means prevention efforts are working, they don't know.

For domestic violence, the data show a drop of 300 cases — but the agency has narrowed the types of cases it will investigate, because of budget cuts. DCFS doesn't believe fewer spouses are sparring.

"It's going up. More and more [domestic violence] shelters are calling me saying, 'We're full,'" says Del Bircher, administrator of the state Domestic Violence Program.

At Primary Children's Center for Safe and Healthy Families, which investigates and treats abuse cases statewide, "the kids seem to be younger. The abuse seems to be more violent," says Director Julie Bradshaw, a licensed clinical social worker.

In the past, kids may have been hurt when parents lost control. Now, she's seeing cases "that appear to be more torturous."

Referrals to The Children's Center are up 20 percent this year, with an extra 20 to 30 calls weekly. Not all involve traumatized children, but some do, and Goldsmith partly blames the stress of a poor economy.

"Kids are witnessing high levels of violence when divorce occurs. We have a lot of kids who have witnessed parent suicides. We have a lot of kids who are going to bed and they hear doors being kicked in," he says. "We're seeing a lot of peer-to-peer sexual abuse."

For the children who are left with PTSD, he says, clinicians now can offer effective help.

—

A survival kit for 'Mac' • In 2006, McKayde Mortensen watched his mother slam into their windshield after a car rear-ended them at a stoplight near their Magna neighborhood. Tricia Mortensen had taken off her seat belt to pick up a toy for him, she says. She was taken away in an ambulance as he screamed for her to stay.

In his 3-year-old mind, she was sent to the hospital as a punishment. At the time, he believed he didn't get to see her, though he saw her every night. Later, he became inconsolable whenever she left the house, believing she got hurt each time.

He was kicked out of preschools for being violent; his mother says he was acting out because he was angry she wasn't there. His nightmares tapered off but never stopped. He kept re-enacting the crash with his toy cars.

At The Children's Center, therapists treating his PTSD helped him retell the story of what happened, correcting his misperceptions. He was told the accident wasn't his fault, and that it was rare. A therapist put handfuls of paper clips on a table to represent all the times his mother drives and pulled out one to represent the accident.

He learned ways to calm himself, making a "Mac's Feeling Survival Kit." It's filled with written reminders of what he can do when he is upset, such as hugging his parents or calling his grandmother.

The techniques were implemented with the help of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, a federally funded program devoted to improving treatments and access to them. The Children's Center is a member, and Primary Children's, a former member, uses the therapies.

They typically aim to correct children's beliefs that they caused the trauma or could have prevented it, that they're "bad" or damaged.

Adults may think talking about trauma will hurt a child, Primary's Bradshaw says, but children need help to "get that story out," doing what adults may do naturally after an extraordinary event — such as a car accident or a fight.

"You tell the story again and again until you're sick of it," she says. "That's how we integrate weird things into our normal day events."

—

'Monumental' • For children with PTSD who are not treated, the resulting chronic stress can take a toll on their health.

It has been linked with changes to the brain, affecting how children cope with daily stresses. They become more likely to feel threatened, increasing the risk of stress-related diseases later in life, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Childhood PTSD has also been tied to lower academic achievement.

Adults with PTSD related to childhood trauma have been found to have higher rates of depression, suicide attempts, substance abuse, psychiatric hospitalizations and relationship difficulties compared to other traumatized adults, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

But today, the child-stress network saw reduced stress in 63 percent of studied children who received therapy for trauma. About 13 percent got worse and 24 percent stayed the same.

"For the first time in our history, we've been able to effectively decrease children's aggressive behavior," says Goldsmith. "That sort of sounds like: 'Well how hard can that be?' [But] state of the art in the country [has been] if you have an aggressive 5-year-old, you'll have an aggressive 8-year-old."

To find something that works, he says, is "monumental."

—

'He can deal' • McKayde's roughly yearlong therapy, which recently ended, triggered memories, "but they taught him how to deal with those memories and kind of make them so they weren't right there in the front of his head all the time," his mother says.

The 8-year-old takes medication for depression and for sleep, but he can still be aggressive. Tricia Mortensen anticipates he will always struggle with what happened. But now, she says, he can cope. And he's getting A's in school.

"He doesn't have those kind of problems every day like he had before. He can deal with me walking out the door and realize I'm going to get into a car, but I'm not going to get into a car accident."

Jessica says her therapy has unleashed her emotions. She tears up frequently while talking about her past and her future. She hopes that by talking she can recover and help prevent someone else from being bullied.

"I just wanted to try and forget about it," she says, "but it didn't work."

How much trauma?

Estimates vary on how many children experience potentially traumatic events, from 25 percent of kids by the time they are age 16 to around half of all children.

Up to 15 percent of girls and 6 percent of boys will go on to develop PTSD.

Rates are higher depending on the type of abuse. If the trauma is more severe or chronic, the child is more likely to develop PTSD.

Children with a family history of mental illness or who have less social support are more prone to the disorder.

Sources: The National Child Traumatic Stress Network, National Center for PTSD —

Trauma in Utah

From October 2009 to June 2011, 177 children have been referred to The Children's Center for trauma treatment. On average, the children experienced more than two types of trauma:

Domestic violence • 41 percent

Sexual maltreatment or abuse • 29 percent

Physical maltreatment or abuse • 25 percent

Neglect • 23 percent

Traumatic loss or bereavement • 20 percent

Caregiver impairment • 20 percent

Emotional abuse • 19 percent

Source: The Children's Center —

Suspect abuse?

I Utah law mandates immediate reporting if child abuse or neglect is suspected. Call the Division of Child and Family Services' toll-free, 24-hour reporting line at 1-855-323-3237.