This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Dinosaur National Monument • This place just hasn't been its 149 million-year-old self lately.

That will change Tuesday with the return of the main reason any 5-year-old kid or Ph.D. paleontologist ever spent are-we-there-yet hours crossing barren Utah sandstone to get here. After five years of safety precautions and reconstruction, the National Park Service is putting the dinosaur back in Dinosaur National Monument.

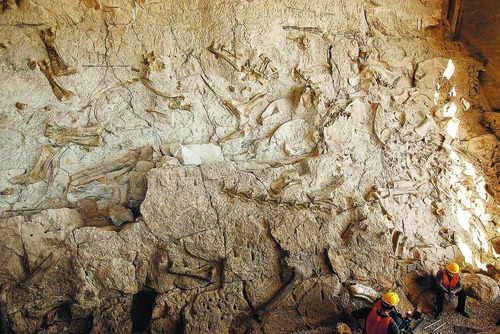

The monument's 1,500-bone quarry — allowing visitors to see and even touch fossils exactly where an ancient river planted them — has returned after structural improvements to the steel-and-glass building preserving it.

It's a one-of-a-kind place where researchers have exposed but not removed a 50-by-200-foot wall of bones.

"Having that magic moment of seeing these dinosaur remains where they were buried is one of the things that is special about this place," park paleontologist Dan Chure said. Even hardened scientists stand in awe when they first arrive. "This wall of bones is really one of the great spectacles — great views — in the entire national park system."

Its temporary isolation, required by shifting clay that threatened both visitors and fossils with a collapse of the 1958-built enclosure, has been obvious at the entry gates. Visitation dropped from about 300,000 a year to 200,000. Vernal motels reported an obvious decline in customers, especially among European travelers who plan their stops months in advance.

Now the eastern Utah tourism engine returns to a regional economy that has relied largely on energy production in recent years.

"I have high hopes that it's going to help us," said Markee Lee Bodily, who bought a gas station and grill just outside the monument this spring. "The Park Service told us it would be a wise idea to have extra staff in here Tuesday."

She's excited about the exhibit, too.

"Last time I was in the quarry, I was on a first-grade field trip," she said. "I'm going next week for my son's birthday."

Of course, there is more to the monument than bones. There's whitewater rafting, along with scenic drives or hikes into canyon country. There's riverside desert camping among abundant but tiny, scurrying lizards. Last week hundreds of sandhill cranes stood and flapped in the Green River on a migratory stopover, their croaks echoing off the hills around the quarry, a reminder of the march of time and biology since the Jurassic Period.

The bones, though, are what first drew the Pittsburgh-based Carnegie Museum's attention more than a century ago, and later the National Park Service. They're still attracting scientific teams — most recently from Brigham Young University — to identify new species in rocks not far from the quarry. Through the years, until the government decided to preserve the rest of the fossils for viewing, universities and museums removed the bones of more than 600 creatures from either side of the remaining wall. Besides 10 species of dinosaurs, the quarry has yielded a crocodile, two turtles, a lizard, tens of thousands of freshwater clams and carbonized plant remains.

At least 100 individual dinosaurs remain exposed, Churesaid, and the profile skull of a plant-eating Camarasaurus is prominent. The other species, whose leg bones, ribs and other remnants are intertwined, include:

• Diplodocus, at 90 feet the longest of the long-necked, planting-eating sauropods found here.

• Apatosaurus, a 60-ton plant eater with pencil-like teeth that show up only at the front of its snout.

• Camptosaurus, a biped, like man, and not any taller, but longer and about 1,000 pounds after accounting for its tail.

• Dryosaurus, another relatively small bipedal plant eater that likely used speed to evade predators.

• Stegosaurus, the spike-tailed plant eater with bony back fins that may have helped regulate its temperature.

• Allosaurus, the most abundant meat eater found among this region's Morrison Formation sandstone.

• Ceratosaurus, a sharp-toothed carnivore with a horned nose.

• Torvosaurus, a meat eater whose Latin name means "savage lizard."

They all lived nearby on what was then a savanna-like plain before the appearance of grasses, Chure said. Paleobotanists believe the landscape was covered with ferns and interspersed with tree groves around water sources. A flood that followed an extended drought washed carcasses or weakened animals into the river, Chure said, and they ended up settling at the channel's bottom.

Scientists historically believed the quarry site was an ancient river bend, but Chure said geologists in the past decade determined that the animals piled up on the channel floor instead of at a sandbar. He said that likely means they were in a straight stretch of river.

The uplifting of the Rocky Mountains running north and south and the Uintas running east and west eventually warped the plain, exposing various points along the sandstone layer on new hilltops.

Besides being safer — the structure is now anchored to bedrock through unstable clay that had buckled it at a former visitor center — the building now offers a closer approach to most of the bone wall. A fence protecting most of the wall now allows an approach within a foot or so, and about a 25-foot-long expanse is open for touching. A second-level balcony above was extended closer to the wall for a better view of higher fossils.

The visitor center, which also had started to buckle dangerously, was removed and replaced down the hill, where a canopy formerly served as a shuttle stop. Visitors still will catch a shuttle from there to the quarry during the busy summers.

"It's really gratifying to see [the] quarry reopen," park Superintendent Mary Risser said. She made the painful but unavoidable decision to close the attraction in 2006. "When you have an engineer telling you you're playing Russian roulette with people's lives, it's an easy decision to make."

As a thank-you for everyone's patience, she's waiving the $10 entry fee through October.

Vacationing Australians Daneen and Wayne Horsfall and their two teenage sons missed it by just a few days, stopping by Dinosaur on Tuesday and camping until Wednesday. They did get to see some fossils protruding from a rock wall on a trail near the quarry. They walked past several exposed sauropod vertebrae before a ranger stationed above them told them to turn around and look again.

"We were hoping that the quarry would be open," Wayne said, but it was memorable nonetheless. They also got to view canyon country in a vintage B-17 — one son's favorite warplane — that was offering tours out of Vernal. "To fly over this country was just spectacular."

The biggest winners could be Uintah County schoolchildren. In years past, they regularly toured the quarry. Retired junior-high teacher Louise Murch led students on weed-eradication projects, after which they were rewarded with an after-hours quarry tour as the sun set through the windows.

"It's always a highlight for the kids — they always looked forward to it," said Murch, now a volunteer in the Intermountain Natural History Association's bookstore at the visitor center.

She hopes a new generation of teachers will restart the program.

"It gives the kids ownership."

Twitter: @brandonloomis —

If you go

October could be an ideal time to visit the quarry. Besides the lack of summer crowds, you won't pay anything. As a nod to visitors, the National Park Service will continue to waive the $10 entry fee that it stopped charging when the quarry closed. The fee for a seven-day pass will return in November. —

The new and the renewed

The Interior Department offered $13 million in federal "economic stimulus" funds to stabilize the quarry shelter and build a new visitor center nearby.

Competition among contractors drove down the actual price to $9 million.

Crews drove 40 "micropile" supports through clay that expands when wet, anchoring the quarry structure to bedrock.

The new visitor center reuses stone from the old building, and its ceiling is the old tongue-and-groove wood floor. It has low-flow restroom fixtures, natural skylight lighting and a photovoltaic system to offset part of its energy costs.