This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

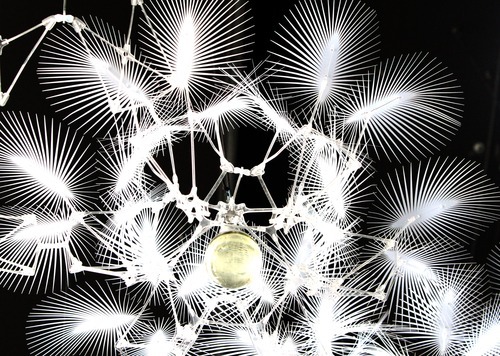

When you first encounter, then react to, Philip Beesley's delicate, shimmering sculpture "Hylozoic Ground" at The Leonardo, it may be a bit disconcerting to know it is also encountering you and reacting back.

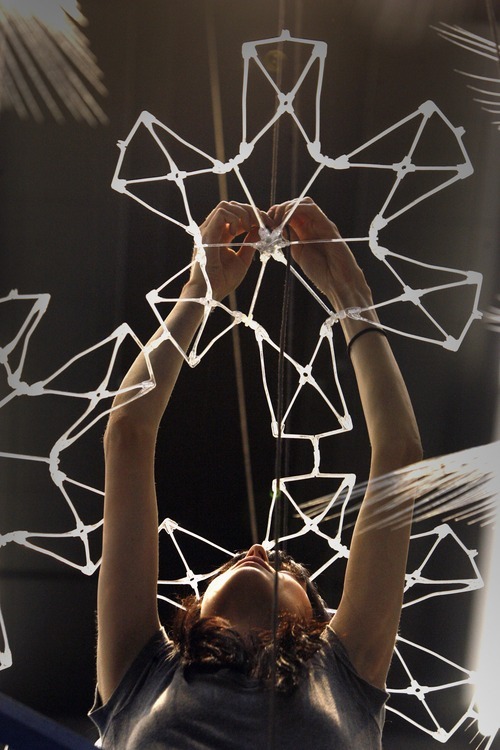

"Hylozoic Ground," which can best be compared to a beehive or jellyfish of synthetic biology and communal intelligence, not only breathes and flutters about the viewers on the Salt Lake City museum's main floor and two floors of escalators — it reacts to their presence by gently moving its featherlike fronds away as they approach.

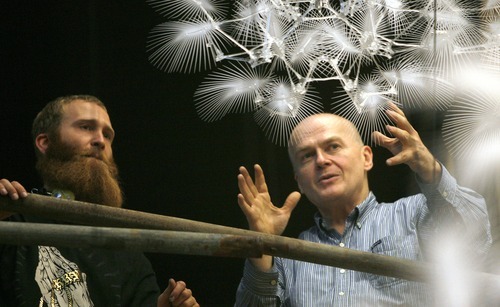

"You have the sense of moving through a crowd," says Beesley, a Toronto-based architect and artist.

Sensors in the sculpture's plumes track visitors' movements, then the impulses are transmitted through the sculpture's neural network much as ripples spread in a pond. Like human muscle fibers, shape-memory alloys in the fronds flex, some pumping air through a rudimentary "great lung," complete with suspended flasks of metallic chemicals that exchange gases with the atmosphere.

"Hylozoic Ground" may point the way to new thinking in architecture in which a structure operates in coordination and cooperation with its human inhabitants to cool, warm and shelter them.

But "Hylozoic Ground" is also a perfect metaphor for the purpose of The Leonardo, itself, which opens Saturday. Beesley's sculpture is a fusion of art, science and technology. It's an architectural experiment, but it is also beautiful.

The Leonardo associate director Alexandra Hesse first encountered "Hylozoic Ground" in Linz, Austria.

"I literally walked into it and was so amazed at the visceralness of the sculpture," Hesse says. "It was unlike anything I had seen before. What Philip was about is so much like what we are about. Everything he stands for fits so perfectly as a symbol of what The Leonardo is about—technology, science, art, the humanities."

Ultimately, The Leonardo bought "Hylozoic Ground" for $750,000 with money it had unexpectedly saved in heating and air-conditioning upgrades to the old downtown library that now houses the museum.

It has been installed temporarily in several cities, including at Venice Biennale. Not only is the work finding a home in The Leonardo, but Salt Lake's culture will likely have an effect on it, Beesley says.

"The sensation [in Utah] is different. The sensation is one of profound connection with the land. Of course, the work inevitably responds to this. It will be interesting to see how the behavior emerges."

Even in a brief conversation, soft-spoken Beesley is obviously more than a gifted artist and architect; he is a thinker who struggles to find ways to express his subtle, yet revolutionary, ideas to others. The result approaches poetry.

"Hylozoic Ground," being art as well as technology, addresses more fundamental concepts. For one, it attacks basic ideas we have about structures and even tools.

"It's very gentle," Beesley says. "Instead of a powerful amplification of your own presence — such as when you pick up a power tool — this is a response that is incremental and atmospheric. It's using a form of language that is quite different."

Unlike the usual on-off, right-wrong responses humans expect of technology, "Hylozoic Ground" is a "mutually cooperative form seeking involvement with the environment," he says. "There is a kind of optimism of give-and-take that is imbedded in this."

Beesley is interested in seeing how "Hylozoic Ground" will interact with the crowds expected at The Leonardo.

"When there are multiple people, it can really get quite intense," he says. "We may want to calm it down because it will get too much stimulation. We may have to program it to let it sleep and chill and not be in party mode all the time. After all, it's here for the long term."

Still, Beesley, as a scientist, is careful to avoid calling his creation "life," even though hylozoism is a belief that all matter has life.

"In some ways it comes alive," he says. "I have to be careful — 'life' is a big word. But living systems certainly have many of the same kinds of characteristic. It's a community, like a coral reef, let's say."

When a journalist points out that "Hylozoic Ground" also is aesthetically beautiful, Beesley smiles. "This work is unapologetically emotional. Some of it works very well and some of it works approximately, and the gestures are of some significance. I'm really happy for it to be an unholy mixture."

In the future, he says, such artificial systems could come to care about the humans they shelter. "We are trying to make a complex system that can start to have its own emotions and start to care about you and in some ways to begin to fertilize itself and create its own environment.

"It's much more like science fiction than science," he says. "That's what I like about it being in The Leonardo. This environment of art and science together makes for a terrifically potent and active kind of space." —

The Leonardo

P The Leonardo, which opens on Saturday, is Salt Lake City's new contemporary art/science/technology museum.

Where • 209 E. 500 South (near the Main Library)

Open • Every day except Tuesday beginning at 11 a.m.

Tickets • Start at $10.