This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Draper •At first glance, it looks like a typical physical therapy room.

There's a replica of a human skeleton, named Frank, hanging in one corner. Actual bones from the various joints that most trouble patients rest on a table. There are elevated chairs for the patients.

But the handcuff loops drilled into the cinder block walls definitely seem out of place in an area designed to promote motion.

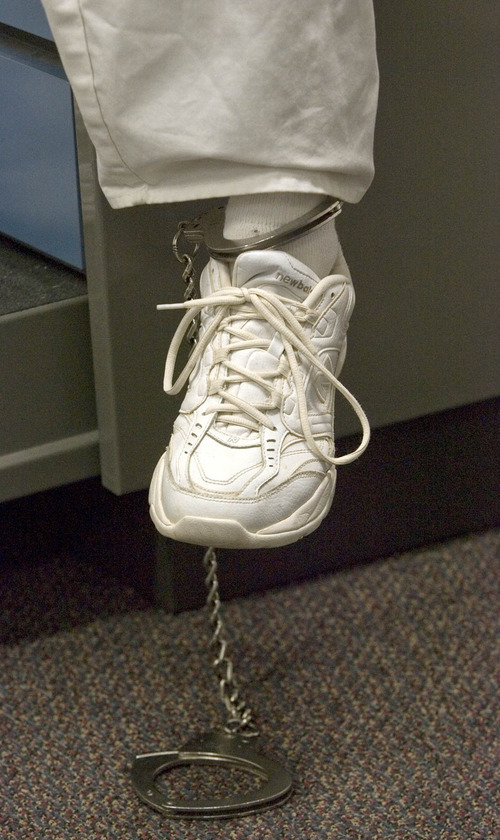

At the Utah State Prison, security is always the top priority, officials say, and that means that prisoners undergoing physical rehabilitation must be restrained.

As officers lead in prisoners who have had knee surgeries to replace torn ACLs, their wrists are chained to their waist, their legs shackled together. The officer hooks their waist chains to the wall, but then unlocks their legs.

"If there's any trouble, I call the officers and the inmate's done," said Bohn Bales, the prison's full-time physical therapist. "They [officers] won't put up with that, and neither will I."

But it's rare for an inmate to cause trouble, Bales said, because physical therapy provides both time out of their cells and helps them feel better.

Bales' presence at the prison also helps reduce medical costs, officials say, because he treats pain before it requires surgery.

Bales has been practicing physical therapy since he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1972. In his nearly 40-year career, he has owned a private practice, worked in hospitals and clinics, and cared for people in their homes. Four years ago, he saw the job posting for a physical therapist at the prison, and he applied.

"I was kind of concerned I wouldn't see a variety here, but I see everything," Bales said.

Most of what he deals with has to do with muscles and bones, such as chronic back pain and torn knee ligaments from basketball injuries and lifting too much. He does have a few patients with neurological issues such as multiple sclerosis and strokes. He sees between eight and 10 patients a day, and travels to the Gunnison prison facility once a week to treat patients there. The care is required under the Eighth Amendment prohibiting cruel and unusual punishment, he said.

There are drawbacks to working in a correctional facility. If there's a lockdown, all prisoner movement stops, which means Bales doesn't get to see his patients during that time. He also has to keep his equipment well away from prisoners as they are being treated. And he can't send them with weights or other implements to work with between visits, as they could be used as weapons. He's had to adapt exercises and teach his patients to use their own body weight to complete exercises.

Burns Tomlinson and a fellow ACL-tearer and basketball player, Mark Johnson, are leaders in their ConQuest group, which provides therapy and treatment to overcome substance abuse issues. Their status as leaders means they have access to weight equipment and stationary bikes, while many other inmates without the same privilege levels do not.

Tomlinson, who is serving his fifth stint in prison, is doing his second bout of physical therapy. He had hurt his hand during one of his earlier incarcerations and was under the care of a previous physical therapist.

"He didn't explain what was going on with my bones and muscles, he just told me to do some exercises," said Tomlinson, who is currently rehabbing his right knee after tearing two ligaments and his knee cap in January while playing basketball. "But this gentleman gives us an understanding of what's happening and why these exercises help."

Bales holds what he calls "back school" and "knee school" to help his patients understand what was injured, the consequences of those injuries and why the exercises he prescribes are helpful.

"I tell them I know these are sissy exercises designed for little old ladies, but they work," Bales said. He added that he has had inmates tell him their knees hurt after several hundred deep knee bends with their cellmate on his shoulders or that their shoulders hurt after doing 1,500 push-ups in a day.

Bales conducts 160 physical therapy sessions per month, but he sees fewer inmates than that because that number includes repeat visits; most patients see Bales weekly or semi-weekly. Surgeries are conducted by doctors at the University of Utah Hospital, and Bales has his patients follow the same physical therapy protocols the hospital employs. Bales says it's nice to not have to deal with insurance companies' restrictions on the number of visits allowed. He can, instead, schedule his patients until they are healed. Inmates are required to pay a $5 co-pay for their first visit.

All inmates who choose to do so are able to complete their physical therapy, prison officials said, which leads to a medical cost reduction and justifies paying Bales about $104,000 a year. Much of that cost reduction comes from managing lower back pain with physical therapy and medication instead of surgery, said Richard Garden, the prison's top doctor.

In a cost comparison of Utah's prisoner medical costs, the Beehive State comes in lower than other prisons with a population of less than 10,000, according to the Corrections Compendium, a peer-reviewed journal published by the American Corrections Association. Utah spends an average of $3,550 per year per inmate in medical costs, which is less than half spent by states such as Alaska, Nebraska, Maine and Wyoming.

It's rare for a prison the size of Utah's to have a full-time physical therapist, Garden said, but it has helped contribute to the lower costs.

And for those inmates who have suffered an injury requiring surgery, having a full-time physical therapist has helped them heal properly.

"This guy is great," said inmate Johnson, who had his knee operated on a month ago. "He's got me back to a full range of motion."

Twitter: @sheena5427