This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Were it not for a touch of the flu last year, Richard Scoville might never have known he was overdue for a blood test that, along with a biopsy, revealed he had prostate cancer — the fast-growing kind.

He might have been spared the hormone injections, which he says felt like "male menopause," the temporary loss of bladder control from surgery to remove his prostate, and the worry that radiation therapy won't kill his spreading cancer cells.

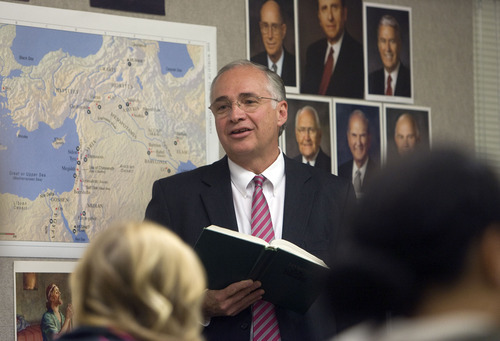

But all of that "is worth a shot at life," says the 60-year-old seminary teacher and father of seven.

It's a story that Scoville thinks men should hear in light of a government panel's denouncement of routine prostate cancer screening.

"If I had gone in for a yearly PSA test and caught the cancer when it was confined to the prostate, I might be cured," he said. "I tell all my friends to go get tested."

Earlier this month the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force — the same group that advised against routine mammograms for women in their 40s — gave prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing a "D" rating.

The test, an annual ritual for men over 50, has yielded little reduction, if any, in prostate cancer deaths, the panel found after a review of clinical research. And it has resulted in needless biopsies, surgeries, radiation therapy and drug treatments that have left men incontinent or impotent.

Plainly put: In healthy men without symptoms, routine screenings do more harm than good.

But many doctors disagree and say the panel's blanket recommendation goes too far.

"We all shudder because we know what it's going to mean," said urologist Jay T. Bishoff, who fears patients will delay or forgo screening altogether.

Bishoff, chief of urology and director of the Intermountain Urological Institute at Intermountain Medical Center in Murray, acknowledges doctors need to be smarter about when and how they screen.

"But prostate cancer is still the No. 1 cancer in men. We can't ignore that fact," he said. "It seems inappropriate, if not cruel, to completely abandon the PSA when we don't have a replacement for it."

No consensus on treatment • Though inexpensive at about $94, PSA tests aren't foolproof. They measure elevated levels of the PSA protein in the blood, which can be a sign of benign prostate enlargement or an infection. They can also indicate the presence of cancer cells.

But many of the cancers detected are small, slow-growing and pose no real threat. By some estimates, 17 of every 100 men tested in the U.S. will have prostate cancer. But only three will die of the disease.

And doctors can't accurately predict whether a patient has the slow-growing or quick, lethal kind.

Even before the guidelines came out, opinions on prostate cancer screening were varied and strong. There's even less consensus on treatment options.

Bishoff advocates early screening. "Do we tell women not to get a mammogram, or tell others to skip their colonoscopies just because there might be a false positive? No, we don't," he says.

Will Lowrance, a urologic oncologist at the University of Utah's Huntsman Cancer Institute, agrees.

"There are good data to suggest there's no need to screen men after the age of 75," as previously recommended by the task force, he said. "But some studies have shown early screening [around age 40] may be predictive of lethal cancers and help establish which patients might benefit from continued screening."

Lowrance further notes that since the mid '90s, when PSA was widely adopted, prostate cancer mortality in the U.S. has dropped 30 to 40 percent.

"The issue isn't so much the screening test, but what we do with the information," he said, acknowledging that doctors have overtreated prostate cancer in the past.

Both he and Bishoff favor a treatment approach known as "active surveillance" for non-aggressive cancers.

"Over the last four or five years we've amassed good data on who you can safely watch and who you can't," Bishoff said, pointing to Roger Holtan as an example.

PSA is just one tool • Holtan was diagnosed with an enlarged prostate in 1999. Even though his PSA was slightly elevated, a biopsy was negative for cancer, so he let it go. But a little over two years ago, a digital rectal exam during an annual physical and a subsequent biopsy caused alarm bells to ring.

While researching treatment options, he was referred to Bishoff, who performed another biopsy. This one came up clear.

Together, they determined that the best course for Holtan, who turns 70 this month, was to monitor the progression of the disease with regular check-ups.

"I have a friend who after surgery is virtually in diapers and another for whom everything came out OK, but he's 14 years younger than I am," said Holtan. "Cancer is an ugly word. Nobody wants it. But I'm very comfortable with my decision. As they say, I may die with this disease, but probably not from it."

PSAs are one tool for monitoring the volume of cancer in the prostate. Intermountain also uses a urine test to determine if someone needs a biopsy, Bishoff said. And work is under way on DNA tests to pinpoint mutations linked to aggressive forms of the cancer.

"In the past, we've looked at a person's Gleason score, which is how does the cancer look under a microscope," Bishoff said. "In the future we'll be looking at a genetic profile of your cancer."

Meanwhile, he said, PSAs remain a first line of defense for patients like Scoville who don't have the luxury of watching and waiting.

Except for a cold, the South Jordan man was healthy and symptom-free last year when his doctor casually observed that he hadn't had a PSA test for three years.

A blood draw showed a spike in his PSA levels and a biopsy confirmed that his cancer had already spread beyond the prostate.

After exhaustive research, including a trip to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, he settled on surgery.

He has returned to teaching LDS seminary at Copper Hills High School. He'll likely undergo radiation therapy later this year and is hopeful.

"I feel great. I felt great when I went into the doctor in the first place," he said. "My plans have always been to live to be 89 or 90."

Twitter: @kirstendstewart —

What's a guy to do?

Here's what the experts say about prostate cancer screening:

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force • In healthy men without symptoms, routine screenings for prostate cancer do more harm than good.

American Urological Association • PSA screenings should be offered to men 40 years or older.

American Cancer Society • Men at average risk should receive information beginning at 50 years, while African-American men or men with a family history of prostate cancer should receive information at age 45.

Confused? • If you have questions and aren't sure which path to follow, talk to your doctor and seek multiple opinions, experts advise.