This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

She was 15 and a sophomore at Cyprus High School in Magna. He was two years older — a senior, a jock, one of eight kids and already living on his own after being pushed out of his single mom's crowded house.

In the crazy-quilt way teenagers sometimes piece life together, Keri Poulsen had two things on her mind when she met Steve Stone.

It was 1986 and, as the Iran-Iraq war raged, the U.S. Army was actively recruiting boys at Cyprus High; who knew how many might go to war and never come home? Second, among her friends, Keri believed she alone was still a virgin.

Within a month, Keri and Steve became intimate and the first time they had sex, Keri got pregnant.

Keri knew the pregnancy would disappoint her mother, a devout member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. So she kept it secret at first, scribbling her suspicion to friends on notes discarded in the trash — which is how her mother found out.

Keri's mother whisked her off to a doctor, who confirmed a baby was on the way. She met with her LDS Church bishop, who brought up adoption.

When Keri called Steve to tell him the news, he was excited, and brought up marriage — even though he'd been dating another girl for more than a year.

Keri said no, a rejection Steve took hard.

But by then, Keri had already visited LDS Family Services, where she said a caseworker told her that if she really loved the baby, she'd do the right thing and give her child a mother and a father, especially since guys like Steve never stuck around.

At weekly counseling sessions, the message was reinforced, Keri said: "If I loved my baby, I would give it away. ... How I wouldn't be able to provide for this baby, finish school and go to college. They reiterate the fathers are just sperm donors and that they don't care."

Steve and his mother opposed adoption and offered Keri and her family other options, including one of those crazy-quilt kind of ideas: Steve and his other girlfriend would marry, adopt the baby and raise it together. Steve refused to relinquish his rights, but neither he nor his family could afford to hire an attorney to fight for custody.

—

It was Keri who selected their baby's new parents from among a stack of applications, arranged so the families' names and hometowns remained secret. Both she and Steve were athletic, musical and creative, and that's the kind of family she wanted for the boy she intuitively knew was coming.

Family A had a 6-year-old daughter. The mother had lost numerous other babies, unable to carry them to term.

"She was a homemaker who gave piano lessons, he was an electrician and volunteer coach," Keri said. "That right there was why I chose them."

As her due date neared, Keri said her caseworker at LDS Family Services suggested the father be listed as "unknown," but she refused. Keri said the caseworker wasn't worried, telling her "we'll get him to sign."

Keri's doctor induced labor on Dec. 23 and by evening, it was all over and she was right: It was a boy.

For Keri, who'd turned 16 by then, the birth and days after are a blur. Keri kept the dark-haired infant in her room, but wasn't allowed to breast feed him.

"I held him, but always with the sense he was not mine, don't get attached," she said.

She didn't feel heroic or noble. Rather, it was, "this is your problem and this is how you're going to solve it," she said.

Mother and child spent three days tucked away in a hospital room as Christmas came and went. On the third day, as she was being discharged from the hospital, the caseworker brought Keri a sheath of papers to sign. "They didn't bring the baby," she said.

That same day, Steve first learned Keri had given birth. According to Steve, the caseworker said the agency didn't need his consent but by signing off he'd be allowed to spend some time with the baby. He signed, and hours later Steve met his son. A photo taken during the visit shows Steve, draped in a hospital gown, seated in a rocking chair and cradling a baby.

—

That January, Keri returned to school, initially attending a program for young mothers, who were shocked she'd chosen adoption. By the mid-1980s, more women were choosing to keep their babies and a precipitous decline in babies available for adoption was under way. Between 1982-1988, just 3.2 percent of unmarried white women relinquished their babies, according to research by the nonprofit Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute. But Keri said she felt she'd made the superior decision.

As soon as she dropped weight gained during her pregnancy, Keri returned to Cyprus High School, where she tried to pretend nothing had happened but "everybody knew my business."

Unable to escape her past, Keri moved to California, where her father lived, to finish high school.

Meanwhile, Steve's other girlfriend was now pregnant but after one rejection, Steve wasn't anxious to make another marriage proposal. In July 1987, his second son was born and that fall, his girlfriend's parents took permanent custody of the infant.

For a time, Steve and his girlfriend remained a couple. But by May 1988, the relationship was crumbling and during a Memorial Day weekend trip to Lake Powell, Keri and Steve bumped into each other again. There was, again, an instant attraction.

But as they got reacquainted that weekend, "there was no conversing about what we'd been through," Keri said, "just honoring that love we had always had for one another."

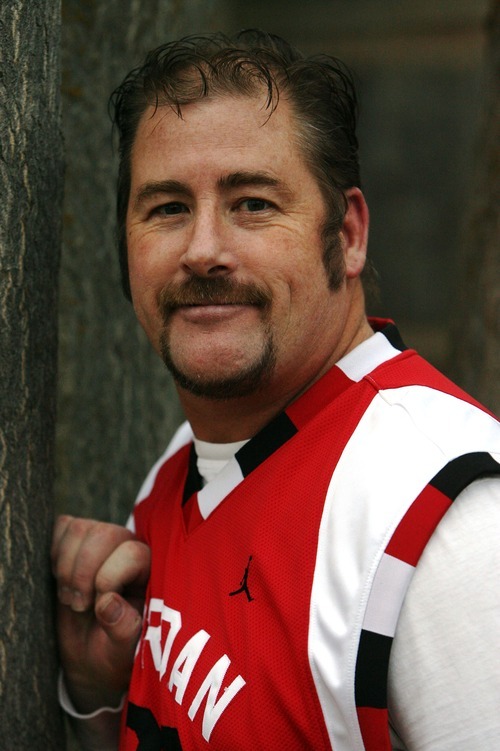

Two months later, Keri and Steve married. They celebrated their 23rd wedding anniversary this summer.

—

While they'd carefully avoided talking about their first-born son initially, there was no avoiding it as they began life together.

"We'd get in fights and he'd use it against me," Keri said. "Even now when we get in fights or arguments, he'll always say, 'I didn't want to give him up in the first place.' "

The baby was gone, but not forgotten. The Stones even kept his birth photo prominently displayed in their home.

Shortly after they married, Keri contacted LDS Family Services and asked how to let the adoptive parents know their child's biological parents were together and willing to share information.

Today, more than 80 percent of adoptions are open, allowing varying degrees of contact between birth and adoptive parents, according to various experts. But that wasn't the case two decades ago.

The caseworker said that wasn't possible but suggested Keri sign with an online adoption registry, so their son, once he was an adult, could find them if he wanted to know about his biological parents.

Keri did so, including birthdate and place, information about herself and Steve, and everything she knew about the adoptive parents, even noting they had "light copper-colored hair."

She altered her son's birth year, and revised it annually so their son stayed perpetually 18, ensuring the information remained public.

Meanwhile, there was a cruel twist in Keri's life: After five years of marriage, Keri found she was unable to get pregnant.

"I sacrificed my firstborn kid and now I can't have any?" Keri said. "I was very angry at the world, very angry at God."

The Stones turned to infertility treatment when they failed to conceive another child and in October 1996, Keri gave birth to Dallen Kale Stone. Keri said it took her months to overcome the emotional wall erected during her first pregnancy. Rather than dwell on the past, Steve focused on the newborn in his arms.

"We had to get used to the idea he wasn't going anywhere," said Steve.

After a second round of infertility treatment, the Stones added a daughter, Kirah Dawn, in March 1999.

—

In 2005, the Stones moved to Texas, leaving their unsold home in the care of a Realtor. They had been in Houston two weeks when their agent called with an odd request from a prospective buyer: He wanted to talk to the Stones. When Steve called, the man quickly confessed he didn't want to know about the house.

He wanted to know if Steve and Keri had placed a child for adoption in 1986.

It was their son's adoptive father, and he told Steve his wife had been searching the Internet and accidentally stumbled on Keri's adoption registry post.

His son's name, Steve learned, was Kai Blakesley and he had grown up just four hours away, in Rawlins, Wyo.

For Keri, the call set off an overwhelming swirl of emotion.

"You hope this day will come, you think it never will," said Keri, who has written a self-published book titled, Life Goes On about her experience.

Kai's dad had lots of questions about the Stones, and lots of news about Kai, whom he described as an outstanding kid who'd received college scholarships for both basketball and theater. Soon, photos of Kai arrived in the mail, and they were a shock, Keri said.

"I was so programmed [about how adoption worked] that I thought he would be as different from us as a red-headed freckly kid," she said. Instead, he looked just like them — and even sounded just like Steve, she learned, after they spoke by telephone.

Kai was going through a similar emotional upheaval. He was nearing the end of his first semester at Casper College when his parents came to see him in a performance of "Hello Dolly!" Afterward, they went to iHop, where his parents broke the news.

"They said they'd found my birth parents, talked to them over the phone, and that I had a little brother and sister and they wanted to meet me and come to Wyoming for my birthday," Kai said.

He broke down, crying, as soon as his parents handed him a family photo of the Stones.

"I could feel a connection, that that's my family," said Kai, adding that he'd always wanted a little brother and sister.

—

Kai said he had grown up knowing two things: he was much loved, and he was adopted.

As a young child, Kai sensed he was different. For one thing, everyone else in the family was blond, and his hair was so dark. Otherwise, he fit right in as a Blakesley — which is, after all, exactly what Keri had hoped when she picked the family.

"My sister and I were both really into sports," said Kai. "My mom loved singing and playing the piano, and I had a love for that as well."

But from the time he was old enough to understand what adoption was, "my mom and I would always talk about it," he said. The Blakesleys declined to be interviewed, leaving Kai to tell their story.

Kai had a blue ceramic Teddy bear Keri had made before his birth, and a letter from his maternal grandmother that explained the situation and how much they all loved him.

"I understood that, and I was always really grateful for it," he said.

As he got older, Kai said his parents asked occasionally if he wanted to search for his biological parents. Not really, he'd said. He was curious what they looked like, to "see where I got my nose, that kind of thing [but] I never really had that concern. I was happy. My parents were really great," Kai said.

So the first few phone calls between Kai and the Stones were "intense," he said.

In December, the Stones traveled to Wyoming to meet their son, arriving in time to celebrate Kai's 19th birthday. Keri said she felt an instantaneous connection to him.

"It was very hard," she said, "but instant love. It came at six months for my other children, it came at 19 for him."

The Blakesleys shared photos and videos from Kai's childhood — his first musical, first dunk, first touchdown pass; the Stones followed with images from their life — the life Kai had missed out on all those years.

Right from the start, there were clashes of expectations as each family tried to figure out to what extent and how to mesh their lives.

For instance, Keri was hurt at not being asked to stay for Christmas.

"You expect it is going to be one big, happy family and they are going to adopt you like a daughter," said Keri. "They love your kid so, of course, they are going to love you."

But it isn't that simple.

—

Months later, Kai briefly moved to Texas to live with the Stones, which allowed him to spend lots of time with his younger siblings. But he admits he was at times a bad influence and "wasn't the best kid." The Stones had issues, too. Among other things, they'd just learned Steve had fathered a daughter with another woman.

Friction between Keri and Kai escalated over his behavior, and Keri ended up kicking Kai out. "It didn't end on a good note," Kai said.

They didn't speak for six months. By then, Kai had a spiritual experience that straightened him up overnight; he again began visiting the Stones, who had moved back to Utah, on his college breaks. In 2008, a new job brought the Blakesleys to Utah, which made it easier for Kai to split his time between two families. But being closer didn't eliminate the conflicts, particularly between Keri, Kai and Kai's parents.

There was a lull when Kai went on a service mission to Mexico for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but it started anew at the airport upon his return. Kai hoped everyone would be civil, there would be no awkward moments, no hard words or mean looks. But it went just as he feared when one family had to be greeted first, the other second, revealing well-dug emotional trenches.

"The whole thing has been really dramatic, a never-ending drama," he said. "It kinda sucks sometimes. I am in a battle to please everyone."

Kai said he is glad he was adopted, given where Keri and Steve were in their lives when he was conceived. But he is just as glad he and the Stones have found each other now.

"I have a sincere, great love for my parents and respect for them. I was raised well," said Kai, who married earlier this year. And Keri and Steve? "Now we're back in each other's lives. Let's be happy with that. If we could all get along, it would be wonderful. Love each other, be one family."

While Kai and his younger siblings initially fit together like the last pieces in a puzzle, the ones that make the picture complete, little brother often feels displaced by big brother and it's "not all cheery and chummy," Keri said. "There are a lot of upsets, there are ripples."

Especially for her. Buried emotions have surfaced, leaving Keri feeling at times unappreciated, like a disrespected ex-wife or, she said, a mere vessel.

There's unresolved grief, anger and regret. She now questions the decision she made in 1986 and believes unmarried pregnant women should be supported so the relationship between a child and its mother is only rarely severed by adoption. It's a view Steve shares.

"Love one another, adopt the mother," said Keri. "If we want to preserve families, let's start there."

Editor's note

Today, the vast majority of domestic adoptions are open, allowing some exchange of information between birth and adoptive parents. But that's not the way things were in 1986, when this story about a birth mother and the child she placed for adoption begins. This is the last of four stories examining adoption in the context of unmarried fathers' rights under Utah law. See the links above for previous stories in the series.

—

Interactive timeline

View an interactive timeline of lawsuits filed by putative fathers at http://tinyurl.com/bsbwqzq