This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

They've survived poverty.

They persisted in secret under the reign of an anti-Semitic dictator.

Now, they must overcome relative obscurity to flourish.

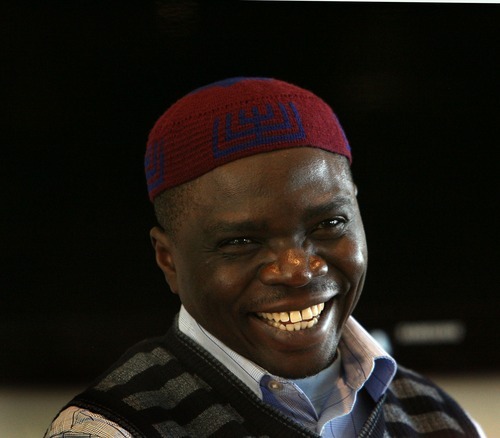

It's a message Rabbi Gershom Sizomu brought to Park City's Temple Har Shalom recently as part of his travels to cities across the U.S. in hopes of educating others about his people — a nearly century-old community of Ugandan Jews called the Abayudaya or "People of Judah."

Uganda isn't a place that typically springs to mind when people think of Jewish populations around the world. But Sizomu, a small man who exudes an air of calm, wants to change that. He hopes to turn his 1,500-member community of mostly poor subsistence farmers into a thriving center of Judaism in Africa that will benefit his people and their Christian and Muslim neighbors.

Sizomu, his community's first officially ordained rabbi, knows it can't be done alone.

"We cannot do this in isolation of established Jewish communities," he said.

He hopes that through his travels — such as from the impoverished villages of eastern Uganda to the snow-capped mountains of posh Park City — he can help his people connect with other Jews around the world.

"Community is such an important Jewish value, that to be an isolated group of 1,000 or 1,500 Jews in Uganda is not enough to sustain a community," said Har Shalom Rabbi Joshua Aaronson. "They need to know they're part of a larger community of Jews."

It's a community that's known little but isolation since its beginning.

Sizomu said it all started in 1919 with a Ugandan man named Semei Kakungulu.

"After reading the Bible, [he] decided Judaism resonated more with African traditions," Sizomu said. "So he went back to the Christian missionaries and told them he had found the truth, and the truth was Judaism."

At that point, Kakungulu was circumcised, in keeping with Jewish law, and adopted Judaism as his religion. The community had about 8,000 followers, Sizomu said.

But tough times followed.

Kakungulu died in 1928 of pneumonia, and the community's numbers dwindled to fewer than 2,000, Sizomu said.

Then, in 1972, life got even harder.

That was when brutal Ugandan dictator Idi Amin — perhaps best known to Westerners for his involvement in the hijacking of an Air France plane by Palestinian terrorists who then held Israeli passengers hostage at a Ugandan airport — outlawed Judaism in the country.

It was a huge blow to the Abayudaya. Sizomu's father, also a rabbi, even was arrested at one point for building a sukkah for the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, Sizomu said.

But the community kept its faith alive.

"We kept our Judaism indoors," Sizomu said. "We prayed for the defeat of Idi Amin."

Those prayers eventually were answered, during Passover of 1979. In celebration of the happy news, Sizomu's grandfather, also a rabbi, announced the Abayudaya could drink more than the four glasses of wine Jews traditionally drink during the Passover seder.

"Many people were not able to walk out of the room, but everyone was so happy," Sizomu remembers.

Sizomu, who was about 10 at the time, thought it a miracle. He decided then that, like his father and grandfather, he would one day become a rabbi. His classmates even started calling the young boy "rabbi," a title that came to replace Gershom as his legal first name.

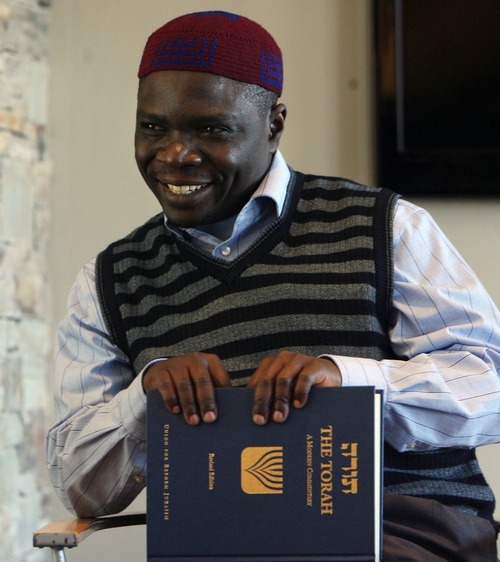

He went on not only to become the Abayudaya's first officially ordained rabbi, but also the first black rabbi from sub-Saharan Africa to be ordained at an American rabbinic school, which he attended for five years thanks to a scholarship from Be'chol Lashon, a San Francisco-based nonprofit organization that seeks to strengthen the Jewish people through ethnic, cultural and racial inclusiveness.

In 2008, Sizomu returned to Uganda, where he established a yeshiva to train more rabbis. The school now has eight students.

"You need to learn Judaism in order to be a leader of the Jewish people," he said.

Over the past decade or so, Be'chol Lashon has worked with Sizomu and the Abayudaya to improve health care in Uganda, such as by drilling wells, distributing mosquito nets and building a health center to benefit all members of the community, regardless of religion.

Diane Tobin, founder of Be'chol Lashon, called the Abayudaya a "role model for the rest of the world in terms of working peacefully" with their Christian and Muslim neighbors.

Be'chol Lashon also has sponsored Sizomu's trips to the U.S. over the years to help raise awareness of the plight of the Abayudaya, some of whom live in mud brick homes without electricity.

Temple Har Shalom members Jill and Steve Edwards, who have worked with the Abayudaya over the years, have been instrumental in connecting Har Shalom with the Ugandan Jewish community. In 2008, Har Shalom's religious-school students raised money to buy mosquito nets for more than 1,000 families there, and around that same time Sizomu first visited the Park City congregation.

The Edwards family hosted Sizomu during his recent Park City visit as well.

Jill Edwards said she had no idea Jews lived in Uganda before she met the rabbi while he was a student at rabbinic school in California. She said it's important more Jews and others throughout the world know of the Abayudaya's existence.

"We don't want them lost," she said. "Unfortunately, so many small communities in Third World countries around this world get absorbed — the dictators, the rebels, [there are] people that just run them over because people didn't know they were there until it was too late."

The Edwards family has traveled to Uganda several times to help.

"The thing that struck me the first time I went there is here is a community of people that are extremely poor and have nothing and they were more spiritual and joyful than people I know who have everything," Jill Edwards said. "They were willing to share everything with us, whatever they had."

Several Har Shalom members who attended one of Sizomu's recent talks in Park City said they also had never suspected a Jewish population lived in Uganda.

But now that they do, they said they hope to spread the word.

"Anyone interested in humanity and kindness to other people can relate to what he's trying to do," said Peter Linsey, a Har Shalom member who listened to Sizomu speak.

Many hope to give the Abayudaya the support they need to become everything Sizomu envisions they can be.

"Uganda will be the center of Judaism in Africa," Sizomu said, "and from Uganda we will strengthen other Jewish communities and Africa."

How to help

The Abayudaya are a community of Ugandan Jews. If you would like to help efforts to provide health care, education, economic development and freedom to practice their religion, you can make a donation through Be'Chol Lashon, a San Francisco-based nonprofit organization that seeks to strengthen the Jewish people through ethnic, cultural and racial inclusiveness. To make a donation, go to http://www.globaljews.org or call 415-386-2604.