This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Seventy years ago, a crew of artists working for the federal government camped in Utah's Horseshoe Canyon, sketching, photographing and measuring panels of Fremont pictographs that were perfect examples of the Barrier Canyon-style of rock art.

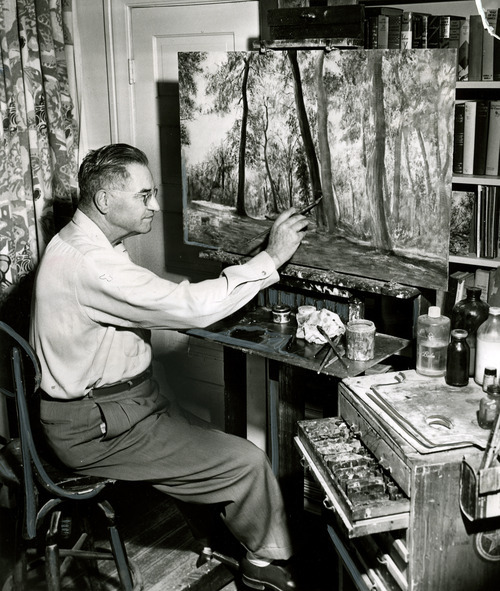

Utah painter Lynn Fausett, known for his large-scale works of Mormon pioneers and frontier community building, led the effort to transfer these images onto two massive canvases. In two parts, he re-created the famous rock art panels as a portable mural.

And unlike its rock art inspiration, the mural turned out to be very portable. The paintings moved around the country for years as artistic vagabonds, even changing ownership a few times before returning permanently to Utah in the early 1970s.

The primary canvas, titled the Barrier Canyon Mural, made its final move last month. This time, it traveled just a couple miles across the University of Utah campus, to a location in the new Natural History Museum of Utah that officials hope does the masterpiece justice and preserves it for generations to come.

The earth-toned mural is the first thing visitors see when they enter the new museum. "It's a link between many times and places," said Ann Hanniball, the museum's associate director. "It was made so many years ago by a prominent Utah artist, about a place that is so extraordinary, and captures ancient art. The layers of time and distance and interpretation — I think it's marvelous."

—

The art of science • The painting also illustrates how the university has worked to incorporate art into the museum, which last month reopened in its new home at the Rio Tinto Center. Officials commissioned artists to produce visual, sculptural, installation, video and audio pieces to accompany dozens of displays.

For the Past Worlds gallery, for example, Montana artist Doug Henderson drew vegetation that scientists believe covered Utah during four prehistoric periods — the Jurassic, the Cretaceous, the Eocene and the Pleistocene.

Landscape and wildlife photographs provide backdrops for the Land and the Lake galleries. Wildlife recordings gathered by Jeff Rice animate the dioramas, while commissioned installations provide thematic frameworks preparing visitors for their journey through the building.

A virtual companion piece to the mural is an installation by media artist Susan Narduli, depicting contour lines etched into the entry patio and images projected onto panels leading up the stairs.

"Susan Narduli also makes reference to the landscape," Hanniball said. "It is a beautiful dance between the material reality and the work of the artists."

—

Painting history • The story of how Fausett created the mural and its travels is recounted in retired museum director Don Hague's 1975 master's thesis for a graduate degree in art history, which he researched not long before Fausett's death.

Hague doesn't label the mural as great art, but instead as a crucial historical document. "It's irreplaceable," said Hague, an artist himself who paints on one of Fausett's easels. "To get the texture, the feeling and ambience with a team of artists and photographers would be next to impossible."

The former director, now 85, is depicted in a portrait hanging in the new museum.

The New Deal-era program Works Progress Administration commissioned Fausett to paint the mural under the Federal Art Project, which employed 5,000 artists during the Great Depression.

Fausett also supervised WPA murals at the Price City Hall, at the University of Wyoming and in Ely, Nev., depicting the founding of White Pine School, according to Hague's thesis.

The rock art mural was new territory for the painter, who grew up in Price and studied at Brigham Young University.

Without Fausett, who was sick at the time, six artists visited Horseshoe Canyon near the Green River in what is now Canyonlands National Park in August 1940. The canyon is home to the Great Gallery, which features many panels of large, ghostly, limbless humanoid figures that typify the Barrier Canyon style of prehistoric pictographs.

—

More than a reproduction • They returned to Salt Lake City with sketches and photos. That fall they set up a large makeshift studio in rented space at 222 S. West Temple and went to work to re-create the pictographs painted a millennium earlier by Fremont artists on Navajo sandstone.

They applied tempera paints to a flexible base in anticipation of shipping the canvases.

The muralists worked hard to also depict the rock matrix below and around the pictographs, showing cracks and desert varnish.

"It is not just a reproduction of rock art," Hanniball said. "You can see the artist's hand."

That November, the painters shipped the canvases to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, where they were displayed as part of an effort to capture the spirit of American folk art. But the works were soon relocated to the Denver Art Museum after the United States entered World War II.

"It was a protective move," Hanniball said. "It was considered a national treasure. Coastal cities were seen as at risk, so it was moved inland."

—

An artistic bargain • In Denver, rather than being put on display, the Barrier Canyon mural was rolled up and left in storage for more than 20 years before it was pulled out to be put on tour.

The mural, already showing signs of decay, became a key piece in the "Standing Up Country" exhibit organized by the Amon Carter Museum of Art. Fausett himself restored the main canvas in 1964. It was then exhibited in Texas, Arizona, Utah and California before stopping at the University of Utah student union in the late 1960s, Hague reported in his thesis. Fausett began making inquiries into how the state could acquire it.

At the time, the old U. library known as the Thomas building was being renovated to house a new Utah Museum of Natural History, and then-museum director Jesse Jennings became interested. U. officials discovered the Denver Art Museum held title, not the federal government.

Denver sent its curator of American art, Norman Feder, to negotiate a trade. He examined the anthropology collections and identified items whose value amounted to $5,000, according to Hague. He recalls the items included a Northwest coast Indian mask, copper artifacts and a wooden weapon.

A transaction was arranged, with Utah officials figuring they got the better end of the deal. Considering seven artists worked on the mural for four months, Hague estimated the value in labor and materials alone at $16,000.

"While the university collections were slightly depleted by the loss of a few choice specimens, the acquisition of the mural and its return to Utah has been considered, by most, a bargain," Hague wrote in his thesis.

—

An innovative solution • The mural's 20-foot segment, known as the Holy Ghost Panel, was sent to the Prehistoric Museum in Fausett's hometown of Price, where it still hangs.

The main 65-foot panel was unfurled along a wall in the Thomas building's Cooper Anthropology Hall, where it remained for nearly 40 years.

Meanwhile, the mural resumed shedding paint. Before the recent move, officials had the surface stabilized, but they couldn't secure a grant to have it properly restored.

The move to the spectacular new museum building presented another big problem: Where to hang a canvas that big. At 65 feet long and 12 feet high, the mural is believed to be among the largest canvases held by an American museum.

A painting that large practically needs to have a room built around it, but that kind of presentation was hard to incorporate into designers' vision for the new building.

The solution was to shorten the painting and fit it on the 35-foot-long concrete alcove behind the ticket counter in the foyer.

But the canvas wasn't slashed. Officials hired engineers to rig a circular overhead chain, formed in the shape of a dog bone, against the wall. Days before the museum opened, they hung the canvas in an outward-facing loop, so that half of the painting is exposed to the public and the other to the Tyvek-covered wall at any one time. Periodically the chain will move to expose a different portion of Fausett's work.

"It is an extremely fragile piece. To install it securely was a feat," said Hanniball, who is pleased with the result. "It is much more vivid, and you are more aware of the colors."

The art of science

A historic mural of Fremont pictographs created by Utah painter Lynn Fausett during the Depression is just one of a handful of intriguing artistic works on display at the Natural History Museum of Utah.

Where • Rio Tinto Center, 301 Wakara Way, University of Utah campus, Salt Lake City. At the north end of Colorow Drive, next to Red Butte Garden on the east side of Research Park.

Hours • 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily except Wednesdays, 10 a.m. to 9 p.m.

Admission • $9; $7 for seniors over 65 and youths, 13 to 24; $6 children 3 to 12; free for kids 2 and younger.

Info • umnh.utah.edu