This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Located just north of Zion National Park, Kanarra Creek Canyon has become one of Utah's busiest hiking destinations, but the 2-mile trail to a slot canyon and waterfalls also introduced at least 40,000 people to Kanarraville's watershed last year.

With no restrooms or prohibitions against pets and horses in the canyon, town leaders fear the recreational traffic could degrade the drinking water, which comes from a spring on a state trust section near the falls and is piped to tanks at the canyon's mouth.

The southern Utah town of 350 is now pursuing a leasing deal with the Utah School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration (SITLA) that would enable officials to severely limit the number of people hiking the scenic canyon, even though the trail crosses public lands.

Town Manager David Ence said officials would be remiss in not protecting Kanarraville's year-round drinking water supply, which he noted is "at ground zero for the hike."

"It's being loved to death," Ence said. "Last year was over the top. Nobody could believe it. On Labor Day we estimated 3,000 people. It was a parade of people."

Ence anticipates limiting trail access to 20 hikers a day. That's on par with some of Utah's most coveted hikes such as Moon House and the Wave, yet far less than the 300 who now visit on a typical weekend day.

The proposal worries public access advocates, especially if it's approved without first exploring other options that don't restrict access and figuring out whether recreational use is actually hurting the town's water.

"They need to go through that process of determining the carrying capacity and what the impacts are, and there's no way to know that if you don't test the water quality," said Erik Murdock, policy director for the Access Fund, a climbing group not directly involved with Kanarra Canyon.

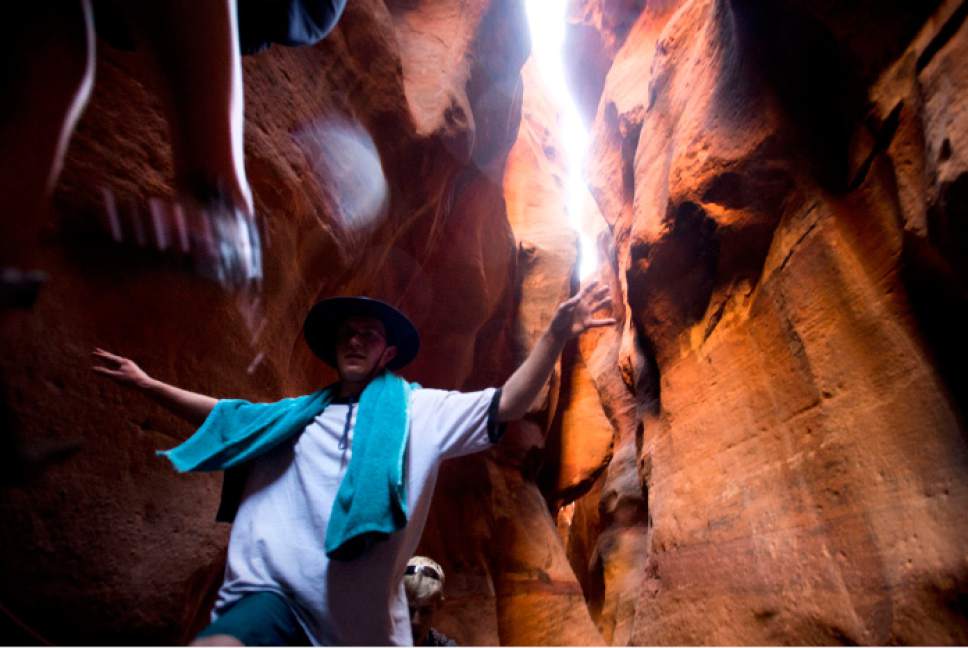

Thanks to the internet, the canyon has been discovered by Utahns displaced by the huge crowds at their national parks. It is conveniently located off Interstate 15 about 10 miles south of Cedar City and offers a rewarding path through a slot sculpted in sandstone. It may be technically challenging, but the hike attracts lots of families with children. The trip starts from a town-owned trailhead, where visitors are to pay $10 to park, and crosses federal land for about a mile.

Tapping the Land and Water Conservation Fund, the Bureau of Land Management spent $660,000 acquiring 41 private acres at the canyon's mouth last month to ensure public enjoyment of the public lands beyond. The agency is sensitive to Kanarraville's plight and is collaborating on ways that balance competing interests.

"We are going to continue to work with the city, Iron County and stakeholders to come up with strategies to address issues as they come up," said Keith Rigtrup, acting manager of the BLM's Cedar City field office. "There isn't anything BLM is aware of that are causing huge issues. It is 1n everyone's interest to protect the water and continue allowing the recreational use."

But the agency's options remain limited because the trail follows a public road before entering the slot canyon. Visitors walk in the creek for the last mile to the falls, but that land is a state inholding inside the BLM's Spring Canyon wilderness study area.

"It's a difficult discussion because we don't manage the attraction and we don't manage the trail head," said BLM spokesman Christian Venhuizen.

According to minutes from a recent town board meeting, it will cost the town $48.75 per acre to lease trust lands in the canyon where it already holds an easement for its pipeline. The town will need to secure 20 to 40 acres below the falls to accomplish its goal of controlling access, at a cost of $1,000 to $2,000 a year.

SITLA officials say the point of the proposed lease is to improve management of the water resources and infrastructure, not lock out the public. Education will be a major part of whatever solution the town adopts, according to Ence.

"If they know it's a water system, they are cautious about it," he said. Ence has seen no problem with litter, although graffiti has appeared on the canyon walls.

But others say the town can do more to protect its water, such as discourage people from bringing dogs and replace the portable toilet at the trailhead with a permanent restroom by tapping revenue from the parking lot, which amounted to $67,000 in 2015.

"If they take the money and not spend it on the resource, a lot of recreationists would have a hard time with that," Murdock said. "They would see it as extortion."

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Brian Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713.

Twitter: @brianmaffly