This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

A new report shows the state's Tongan and Samoan communities have more than twice the rate of obesity and nearly double the rate of adult diabetes of other Utahns, and a cultural belief that larger moms and babies are healthier puts infants at risk.

The disparities are even wider than the Utah Department of Health presumed after analyzing death certificates, which showed high rates of diabetes and infant mortality. The new assessment is based on a survey of 605 adult Pacific Islanders in Tongan and Samoan as well as English.

"It was a genius idea," said Jacob Fitisemanu, an outreach specialist for the Health Department.

Having translators do the questioning helped adapt the use of analytical software geared to English, and made the findings more meaningful to researchers and the Islander community, Fitisemanu said.

The department believes it may be the first study of its kind to examine mainland Pacific Islanders in the United States. Community members were involved throughout, from suggesting questions to promoting the survey, the department said. It hopes to use the results to help guide Utah's Islanders to better health.

April Young Bennett, spokeswoman for the department's Health Disparities Reduction office, said the interviews revealed an "extremely high" obesity rate, even after researchers adjusted the body-mass index obesity standard from 30 to 32.

"Some research does suggest that Pacific Islanders can be healthy at a slightly larger size than Caucasians," Bennett said. "We still found that about half of Utah Pacific Islander adults were obese."

The study also found:

• Pacific Islanders interviewed in Tongan were particularly likely to have diabetes, with a rate of 44 percent.

• Although only 15 percent of Pacific Islanders were at healthy weight or underweight according to the customized BMI, 33 percent perceived their weight as healthy or underweight.

• Compliance with guidelines about early prenatal care was low, with nearly half of infants born to women without prenatal care, more than half of women not breastfeeding two to six months after their babies were born, and more than a third of women getting pregnant again in fewer than 18 months.

For the past few years, the National Tongan American Society, based in Murray, has been working with the health department to educate the community about the risks a large size may pose. But that awareness has had to fight a cultural bias, said Ivoni Malohifou'ou Nash, the society's program director.

"We thought big is beautiful. We still are beautiful," Nash said. "But when you are huge you get diabetes, you get [a] heart attack."

Pregnant women, she said, "are the princess of the family. You don't do anything. The whole family feeds you."

That bias extends to babies, she said. An 8-pound infant is too small. A 10-pound baby is prized.

Women don't focus on nutrition, Nash said, and are told if they eat pork, salt and taro root, their milk will be better, but if they shower or exercise after giving birth, their milk will go away. Gestational diabetes may be the result of such advice, putting the mom's and baby's lives at risk.

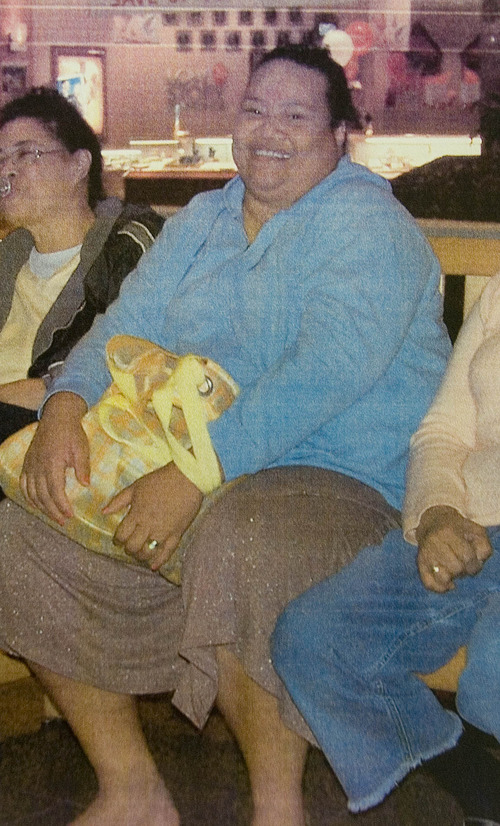

In the islands, skinny people get teased, said Salt Lake City resident Rena Lakai. "I was born skinny," she said. "Kids made fun of me."

But skinny in the islands is a different concept than skinny in the white culture, Nash said. A women's size 18 is skinny to her culture. Size 33 defines huge.

Which made it easy for Lakai to still feel comfortable when she weighed 340 pounds, especially when her doctor found no sign of diabetes and told her she was healthy. That gave her an excuse not to lose weight, she said.

But when her father told her in all seriousness that children are supposed to bury their parents, not the other way around, she started thinking it was time to get some exercise and eat right. The final push was when she couldn't bend over far enough to tie her own walking shoes and had to ask her brothers for help.

She started walking with groups of Islanders at the Valley Fair Mall and Arrowhead Park in Murray. She ate fish instead of meat, fruit and vegetables instead of sweets and less of all of it — which probably is the healthiest way to lose weight for life.

A year and a half later, she was down to size 14 and less than 175 pounds. Now her goal is to fit into the size 12 dress she has hanging on her wall. "I'm so obsessed with that dress," Lakai said. "I try it on every day."

The study results are a starting point for the Health Department's continued education efforts. "We've never [before] had a baseline to go off," Fitiseamanu said.

The information, including a video now on YouTube, has been spread across the Internet, as well as community, church, civic and education hubs. "The way it works with our community is really word-of-mouth," he said.

The next step is to figure out how to measure the effectiveness of the education campaign and to get more people involved in the 8-week MANA fitness challenge, which uses the pan-Polynesian concept of "mana," or life force, to create the acronym from the words movement, awareness, nutrition and action.

"We're never going to lose as much weight as on 'Biggest Loser,'" Fitisemanu said, but added that eight weeks is enough time to develop new good habits for the Islander community.

Twitter: @sltribhenetz —

Pacific Islander health study

For the first time in the nation, health researchers have interviewed adult Pacific Islanders in Tongan, Samoan and English about their health. The findings have given the Utah Health Department new ideas about how to spread their anti-obesity message to the communities, whose cultures praise large size.

To see the full report • http://1.usa.gov/tjUTf6

To see the videos • http://1.usa.gov/u7IzOe