This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

One of the paradoxes of learning how to invest is that the best advice sometimes comes from experts who don't always heed their own counsel, and aren't afraid to admit it.

Carl Richards, a Park City financial planner and blogger for The New York Times business pages, concedes in his engaging first book, The Behavior Gap, that he, too, can throw aside caution when the next Big Stock seems ripe for the taking.

"Fantasies are only fun while they last. Back in late 1999, I was resisting the temptation to buy technology stocks — a temptation that was growing more and more powerful by the month. Everyone — my friends, my family my clients — wanted me to buy technology stocks. It didn't help that my brother-in-law works in the technology industry, and he kept telling me stories about people making easy money," Richards writes.

He gave in. Richards made a hefty investment in InfoSpace, a search engine company. The stock price ballooned from below $40 to more than $480 from October 1999 to March 2000 before sinking back to near $8 in March 2001. (Richards recalls that the stock moved from less than $100 to more $1,300, but no matter. The point is the same.)

"That's how it goes. The terrible irony in all of this is that the people who are trying to stick to their [investment] plans — the ones who hold out the longest before they finally capitulate — are the ones who end up getting hurt the worst because they buy nearest the peak. Once those hardcore holdouts give in, you know the top can't be far away, because there is no one left to buy," Richards writes, recalling his folly.

The subtext of Richards' book is how to think about investing without doing dumb things that squander money. Although it's aimed at anyone, The Behavior Gap seems more useful to unseasoned investors wading into Wall Street for the first time or to veterans for whom it isn't too late to rethink their ineffectual game plans. Long-time investors might appreciate the book, if only to lament the mistakes they made — starting with failing to grasp the behavior that gave rise to the book's title.

Richards coined the term "behavior gap" to give a name to the gulf between investment returns and investor returns. Analysts have tried to study the effect of behavior on investment returns. The studies typically compare the returns investors earn from stock funds to the average returns of the stock funds themselves.

What researchers find is that the funds do much better. Why? Because most investors don't put their money into a fund and keep it there. Instead, they hopscotch their money from fund to fund in search of bigger returns. Human nature being what it is, they buy too late, when yields are close to the top, and sell too late, after yields have faltered. It's better to leave investments alone, Richards says.

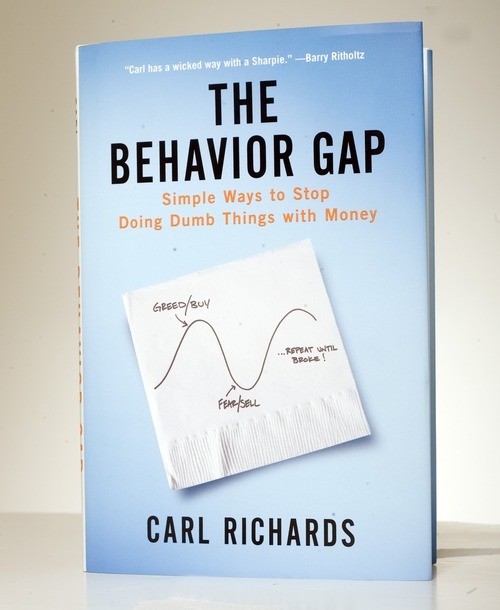

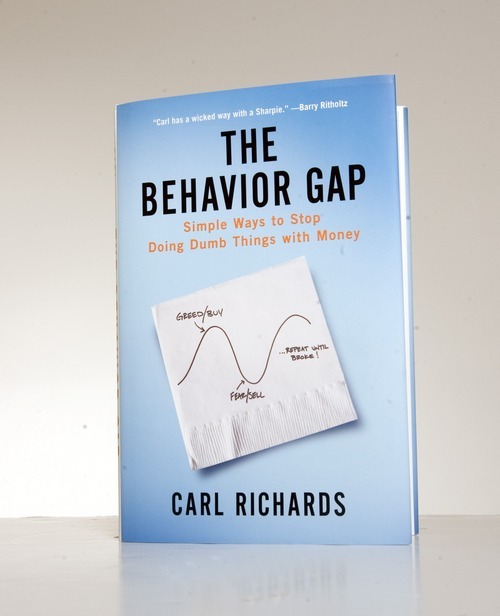

Richards emphasizes this and other lessons with more than 50 deceptively simple black-and-white sketches that he drew with a Sharpie marker pen. Perhaps more than his words, the sketches are his signature. Both appear each Monday in The Times, but it is his elegant squiggles, Venn diagrams, bar charts, flow charts and line graphs that have been shown to audiences at art shows in New York and Park City. The drawings capture complex investor behavior through a genre that he refers to as "visualizing finance."

Like his drawings, Richards has distilled his financial concepts into clear and accessible language. His distinctive style captured the attention of the U.S. affiliate of Penguin Group, one of the largest English-language publishers in the world. Penguin published The Behavior Gap (178 pages, $24.95) under its business book imprint, Portfolio. It is being released this month.

pbeebe@sltrib.com Twitter: @sltribpaul