This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

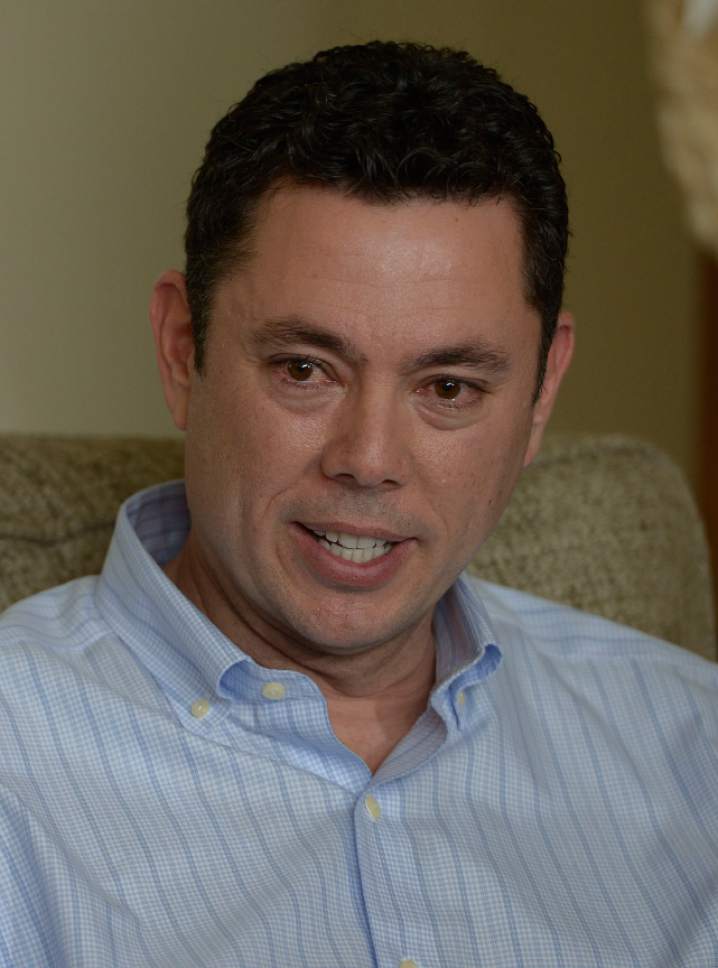

Washington • As Rep. Jason Chaffetz looks to leave office, one of his unintentional legacies could be this: propping up an underground market for marijuana in the nation's capital and making dealers more money.

Chaffetz, R-Utah, helped lead the charge to block a voter-approved law in the District of Columbia to legalize adult marijuana use in 2015. Congress didn't overturn the law but prohibited the district from using any money to implement it, meaning that while residents age 21 and older can possess up to 2 ounces of marijuana and smoke legally in their own homes, the city couldn't set up any system for weed to be legally sold.

Enter the city's nonlicensed, nonregulated purveyors of pot who were more than happy to step up and sell their product to a new customer base.

"Not only has [congressional action] blocked us from writing responsible laws, it empowered the gray market and I guess you could call it the underground economy," says Adam Eidinger, who successfully pushed for passage of D.C.'s Initiative 71 that received more than 70 percent of the vote to legalize marijuana use.

Eidinger, who was arrested twice in the past month for giving away pot on federal property, doesn't like the term black market, he notes, because the line is now more gray on what is allowed. Nonetheless, he says, "It's empowered them."

Chaffetz warned in a letter to D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser in February 2015 that she would be violating the law if she moved forward to implement the legalization of marijuana, noting that Congress had forbid spending any money to do so. Members of the D.C. City Council joked they would be happy to share a jail cell at the time.

Rep. Andy Harris, a Maryland Republican and medical doctor, inserted language into an appropriations bill forbidding the district from spending any money enacting any tax or regulation system for legalized marijuana use like other jurisdictions such as Colorado and Washington state have in place.

The federal district is not a state, and Congress has the authority to overturn laws or budgets passed by its City Council. The district does not have any voting representation in the House or Senate.

D.C.'s chief financial officer has said the city is losing out on $130 million in tax revenue because of the law.

"It's really Andy Harris and Jason Chaffetz who are the two people who should be responsible for the lack of implementation of the marijuana law that was supported by 70.1 percent of the voters," Eidinger says.

Several D.C entrepreneurs have emerged in the void of regulation to provide pot to customers. In some cases, a vendor will sell cookies, shirts or other legal products that will include a free gift of marijuana; the city's law allows for giving a small amount of weed to another person.

Eidinger also notes that there are pop-up events where pot smokers go to a private residence or other locales to smoke because they may not have a place, such as government-subsidized housing, where they can light up.

"As a result, there are smoke-easies," he says, playing off the term speak-easies, the illicit bars that sprang up during America's alcohol Prohibition. "It's like the 1920s."

Chaffetz has drawn the ire of district residents several times during his tenure, most recently when he held a hearing to try to block the city from implementing an assisted-suicide law. The Oversight Committee he heads voted to disapprove the law, the first step to blocking it, but the full Congress never voted to follow suit.

When Chaffetz announced he would leave office June 30 to pursue other ventures, the D.C. City Council tweeted the irony. If Chaffetz resigns and there's a vacancy, the council said, "his [Utah] constituents will have no vote in the House! Imagine how that would feel!"

Bo Shuff, director of advocacy of the group DC Vote, which lobbies for full representation for the district, says Chaffetz's efforts to block the voter-approved marijuana-legalization law was just "one example of Rep. Chaffetz meddling in the affairs of people he doesn't represent."

"Because he's not accountable to the residents of D.C., he seems uninterested in our autonomy, our safety or our ability to govern ourselves," Shuff continues. "He would never attempt to tell neighboring Colorado what it's people should do, but an outdated, oppressive interpretation of oversight keeps him harming D.C. residents."

For his part, Chaffetz balks at the idea that he helped boost the illicit drug market.

"Are you trying to tell me drug dealers love me?" he jokes.

The congressman says it's up to the district's various police forces and federal authorities to enforce the law and crack down on illegal sales. It's still against federal law to use marijuana, even in the district.

In April 2015, Chaffetz sent a letter to then-National Park Service Director Jonathan Jarvis asking him why no one was arrested at an event on the National Mall where pot users gathered to smoke to protest anti-marijuana laws.

"I don't think Washington, D.C., should be the haven for pot smoking," Chaffetz says. "I just don't. And the way the Constitution is set up, all of Congress has input on how it should work. I just don't believe that legalization in our nation's capital is the ideal way to go."

Chaffetz points out that Attorney General Jeff Sessions has drawn a hard line on illegal drugs. The Utah congressman adds that he's interested to see what else the Trump administration would do to attack the nation's drug problem.

Alan Amsterdam — who once owned a coffee shop in the pot capital of Amsterdam and now co-owns, with Eidinger, Capitol Hemp, which sells marijuana pipes and paraphernalia — concedes that what Chaffetz and Congress did was legal.

Even so, Amsterdam decries the move.

The D.C. native hopes that one day he'll be able to legally sell marijuana in his shop and that it would benefit society by bringing the traffic to a brick-and-mortar store and off the streets.

Had the city been able to enact a tax-and-regulation system, he says, "you would have stores like Capitol Hemp that would be regulated" and owners would "fight to the death" to ensure they followed the law to the letter to keep their licenses.

Such an effort, he insists, would help keep weed out of children's hands. "I tell everyone this: Drug dealers don't card, they just want money."

For now, Amsterdam says, the underground market will remain as long as Congress keeps treating the district "like children."

"Any time you have kind of a nanny state," he says, "you're going to have people bubble up in a gray area."