This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Lehi • To reach the monumental bronze Christ striding through storm-tossed waves of Ashton Gardens' "Sea of Galilee," you first must pass through an ocean of desert sand and undulating tufts of prairie grass.

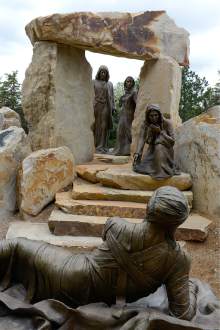

It is an intentional artistic vision and, to many, a spiritual experience in which carefully designed landscaping combines with excruciatingly detailed statuary. Those who enter the gardens' permanent "Light of the World" exhibit are transported back 2,000 years to Palestine — and moments in the life of an itinerant rabbi whose touch is said to have healed, inspired and saved.

But on a late spring day, as she peers up at her larger-than-life work "It Is I, Be Not Afraid," sculptor Angela Johnson says that there is much that is deeply personal in the scene, the first of 15 featuring 35 figures over the 2.5-acre enclosure.

"I see determination and dignity," she says. "I wanted to capture that. ... Here's this big old mass of water, symbolic of the adversity that not only threw itself at Christ, but all of us. It shows the intense aspects of the human saga."

The scene is based on the Matthew 14:22-31 account in which Christ beckons Peter to join him walking the waves. He ends up rescuing the apostle when Peter's frail faith brings him near to drowning.

"I've always had in me a fear of deep water," Johnson says, caressing one of the frozen, dark waves she crafted roiling around Christ's feet. "I've certainly needed Peter-like faith to accomplish all this."

It took her 13 years to complete the $4.5 million spiritual oasis at Lehi's Thanksgiving Point, the final finishing touches completed in September 2016. Johnson is a lifelong Mormon — the last of her 15 scenes shows LDS Church founder Joseph Smith's "First Vision" — but she says the "Light of the World" theme stretches beyond denominational boundaries.

"Light and darkness are universal, tracking across all religions," she says. "It's a starting point for all of us, seeking light in our own darkness."

Johnson refers to her own "dark tale," one of childhood physical and emotional abuse, and her struggles with depression and self-esteem later in life. Blessed with a fine soprano voice and stage presence, however, she sought solace and purpose in pursuing a dream of someday singing in the Metropolitan Opera.

Johnson enjoyed local and regional operatic success, but one day, in her late 30s, she had an abrupt epiphany. While sitting at her piano to begin her daily hourslong routine of vocal work, "I just knew, at that moment, I was not going to realize my dream," she recalls.

She was devastated. What came next, Johnson insists, "was an act of God." It came with an impulse: She got up, grabbed her car keys and drove to an art supply store. There, she bought a single block of clay and one sculpting tool.

Johnson had never given sculpting much thought; she had never had a lesson. Back home, she unwrapped the lump of clay on her kitchen counter and plunged her hands into it. That action, she says, unleashed a surge of energy, passion and the hurt of a lifetime over the next several hours as her first sculpture took form.

"It became the bust of a little girl, in pain," Johnson whispers. "It was me. I completely embraced the experience. The ability was just there."

For Johnson, a 60-year-old Alpine mother of four and grandmother of 16, the nearly 20 years since that first piece emerged brought a string of private and public commissions. However it was her traveling clay exhibit — based on Christ's healing ministry — which appeared in visitor centers for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints throughout the U.S., that birthed her monumental work at Ashton Gardens.

In 2008, she met Karen Ashton, who with husband Alan Ashton had founded Utah's Thanksgiving Point, at a women's retreat Ashton hosted at her cabin in Aspen Grove. After seeing a PowerPoint presentation of the artist's works, Ashton approached Johnson.

She offered to pay to bronze the traveling exhibit — and also shared her ideas for what would become the "Light of the World" garden.

With the Ashtons and the already renowned Ashton Gardens on board, the project soon attracted a surge of donors for what is believed to be the world's largest existing sculpture collection of Jesus Christ.

The exhibit winds through scenes that astound the eye with their humanity, emotions, compassion and exquisite elements.

Here is the adulteress, in anguish, surrounded by a crowd ready to stone her — just before the accusers are shamed by Christ into walking away. There, Lazarus peers toward the entrance to his tomb, called to new life by his Savior.

Another scene captures the touch of Jesus, healing a leper; still another shows a desperately ill woman a second before she clutches the hem of Christ's robe. Nearby, the Apostle Thomas — his doubts so much still in play millennia later — approaches the risen rabbi to touch the wounds of the crucifixion.

In Thomas, Johnson sees not only the beginning of a faith journey that would end with the apostle's supposed martyrdom in India some two decades later. Years ago, Johnson visited the apostle's shrine and tomb in Chennai.

It took probing the nail-scarred hands and spear-torn torso of his Lord, the Bible recounts, for Thomas to believe.

Faith is a tougher proposition in the 21st century.

"I did this to show that the story of Christ is still relevant today," Johnson says, "even through this whole thing now of demands for evidence, for proof of the veracity of this God you worship."

The visitor's eye is soon drawn to a Jesus in anguish, having collapsed beneath a gnarled olive tree in the Garden of Gethsemane. The scene captures the moment he begs to escape his coming torment on the cross, yet submits to the divine will.

Luke 22:44 describes Christ's agonized prayer being accompanied by "sweat ... as it were great drops of blood falling down to the ground."

Johnson renders the suffering in consuming detail, with protruding, pulsing veins on his temples and neck. For the bloody perspiration, she used potash to give the bronze a reddish tint.

Another work, titled "Because of Love," offers an equally grim, stark beauty as Christ struggles to heft a heavy, splintered and oft-used cross up the slope of rocky Golgotha.

"I wondered how to create an old, rugged cross, to give it a history, to make people wonder, 'Who else has been crucified on this cross?' " Johnson says.

From the crown of thorns to the pain and exhaustion of hours of beatings and scourging that preceded his execution to legs straining to carry the weight — no detail is spared. Even the statue's feet, toes gripping the rock, show the struggle.

Still, "Light of the World" balances its terrors and sadness with scenes of triumph and love. The "His Gathering" sculpture may be the most poignant of the latter. In this scene, Christ crouches down next to mother hens and gently guides chicks back to protective wings. That gesture, Johnson says, "charms me and fills me with infinite delight.

"I can put myself under those feathers, feel their softness," she adds. "I can feel the heartbeat of the mother hen, and I wonder, how would it feel to sit so close to the Savior that I could feel his heartbeat?"

Johnson takes in the panorama, the works of her hands, drawn from a once-wounded, now-healed spirit, and her unabashed faith. Then, she looks again at the chicks, smiles and talks about a personal prayer "His Gathering" often evokes.

"Help me not to wander," she says. "Bring me back."

Twitter: @remims —

An artist's perspective

For Angela Johnson, one reward for her 13 years of labor turning visions of clay into monuments of bronze is simply to sit and watch visitors wend their way through her depictions of Christ and his ministry.

Some stand away, reverent and whispering. Others approach the sculptures and touch them. Occasionally, a visitor makes the sign of the cross.

Johnson remembers children crawling into the lap of Jesus. Almost all the adults will, like the Doubting Thomas she crafted as one of 15 scenes, feel the nail scars in the larger-than-life Christ's hands.

Usually, she can watch in anonymity, relishing the interaction between art and observer.

"I love the different perspectives you can show with sculptures like these," Johnson says. "When you stand behind Christ, you just think about things differently."

The musing on a partly cloudy spring day, the sun just beginning to assert itself, suddenly halts when a middle-age couple furtively approach.

"Someone told me the person who did these was here. Are you the artist?" the man asks. Johnson smiles and affirms.

"I didn't expect to visit the gardens and end up with a spiritual experience," Troy Bradley of Layton gushes.

Hugs are exchanged as he and his wife, Kaisa, thank the sculptor before walking on through the gardens.

Johnson appreciates the responses to her work. But she most treasures the personal, spiritual experience of creating.

"I'm always amazed at all the dirt and grime and labor that go into creating something so ethereal," she says. "But I am most in bliss being covered head to toe in clay."

Bob Mims