This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Washington • The founders of the Republican Party saw Mormons as their enemies.

And the first Mormon leaders didn't have much nice to say about the GOP, either.

You would never know it now — one recent poll showed three-quarters of LDS faithful lean toward the GOP — but the two groups had an acrimonious start, fueled largely by the early Mormon practice of polygamy.

As Mitt Romney presses his bid for the Republican nomination for president, lost on many Americans is how his Mormon faith played an important role as foil in the early days of the Grand Old Party — and how its first candidates catapulted to power in part by whipping up anti-Mormon sentiments.

"If you like irony, you've got to love history," says Utah historian Will Bagley. "Polygamy made Mormons into a national punching bag during the 1850s."

The Republican Party launched in 1854 as an anti-slavery party and quickly seized on growing concern with Mormons in the Utah Territory taking on multiple wives.

The GOP's first party platform in 1856 took direct aim at polygamy, placing it in the same sinister frame as slavery in the hope of cultivating the votes of Christians wary of the spread of these dual threats to the republic.

"It is both the right and the imperative duty of Congress to prohibit in the Territories those twin relics of barbarism — polygamy, and slavery," the party declared as it emerged on the national stage for the first time.

Later on, Republicans used their congressional power to wipe away any secular power Mormon leaders had in the Utah Territory and were the main backers of a law that disincorporated The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

LDS Church leaders, for their part, harbored ill will toward the Republican Party, urging followers to back the Democrats.

"We call upon you to stand firm to the principles of our religion in the coming contest for president," read a letter from LDS Church President Brigham Young and other leaders as published in the abolitionist newspaper, The National Era, on Nov. 20, 1856. "Our duty is plain. There are two principal parties in the country — one is for us, the other against us."

The relationship between Mormons and Republicans eventually flipped — morphing into the current-day landslide of LDS support for the conservative party. But things got a lot worse in the relationship before they got better.

—

Polygamy as slavery • San Francisco lawyer John W. Wills claimed credit in an 1890 letter to the Historical Society of California for coining the phrase "twin relics of barbarism" in reference to polygamy and slavery.

Wills says there was some hesitancy by a few GOP delegates to pair the two institutions, in part because some felt that slavery already included the practice of polygamy. But Wills kept the language intact.

"The rapturous enthusiasm with which the resolution was received by the convention," Wills wrote, "was the first convincing evidence that the committee had acted wisely in determining to preserve it in its original form."

Of course, Republicans weren't alone in vilifying Mormons.

Sen. Stephen Douglas, an Illinois Democrat, said in one of his campaign speeches in 1857 that he feared Mormons wanted statehood for Utah so they could use it as an "invincible shield" to protect their "crime, debauchery and infamy."

If rumors of Mormon troubles are true, then "the Mormon inhabitants of Utah, as a community, are outlaws and alien enemies, unfit to exercise the right of self-government," Douglas said, according to a New York Times account of his speech at the time.

After Republican Abraham Lincoln won the White House in 1860 and the Civil War ended slavery, the GOP soon found that polygamy was one concern that still resonated with Americans. Political cartoons of the time included polygamy as one of the GOP's go-to issues to energize voters. Republicans over the next several decades targeted the LDS Church over polygamy and suspicions that Mormons were attempting to form their own sovereign country in the Mountain West.

The fight was driven often by members of Congress from Vermont, coincidentally the birthplace of LDS Church founder Joseph Smith.

U.S. Rep. Justin Smith Morrill, a Whig Party-member-turned-Republican from the Green Mountain State, sponsored the 1862 Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, which banned polygamy and limited ownership in any territory by a church or nonprofit to not more than $100,000.

The LDS Church, of course, had amassed great swaths of land in the Utah Territory, and its followers, including Young, had dozens of wives.

Lincoln didn't pursue the church or polygamists under the act, hoping to find a truce with the saints while he prosecuted the Civil War.

Vermont Rep. Luke P. Poland later amended that law to order that all civil and criminal cases in the Utah Territory be handled by the U.S. District Court and dismiss any other judiciary system in the state that he feared were simply church puppets.

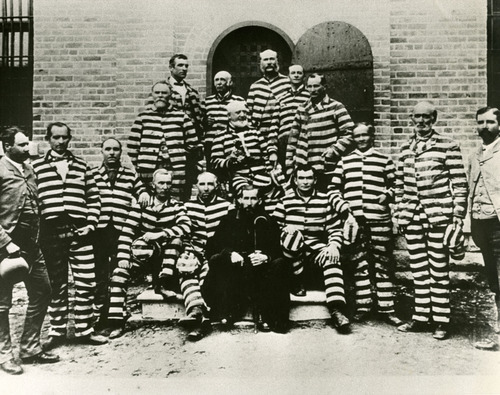

Poland's hope was that the federal courts would then go after polygamists, but it wasn't until the 1887 Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act — sponsored by Republican George Franklin Edmunds — and the subsequent Edmunds-Tucker Act that Mormons with plural wives were prosecuted.

Around 1,300 men were eventually jailed under that act.

The law also was successful in disincorporating the LDS Church, forcing Mormons to take their battle to court. The U.S. Supreme Court later ruled against the faith but Congress took a step back when Mormon leaders issued a proclamation in 1890 banning polygamy. That also was a turning point for the icy relationship between Mormons and the GOP.

—

Turning to the GOP • Mormon leaders, upset with the Democrats' inaction on the long-sought establishment of Utah as a state, looked to the GOP for help. The Republican Party of Utah was founded on May 20, 1891.

"Because of members' previous clashes with the national Republican Party, many church leaders feared that most of the Saints would flock to the Democratic Party and in doing so alienate Republican friends who were working diligently for statehood," according to the Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History. "Therefore, several general authorities used their influence both publicly and privately to encourage members to affiliate with the Republicans."

Utah finally gained statehood in 1896, though it would take decades longer for the Mormon faith to evolve into a Republican-leaning group.

The GOP's take on social issues, such as abortion, the Equal Rights Amendment and gay marriage, drew Mormons into the conservative fold beginning in the 1970s.

Church apostle Ezra Taft Benson, who supported the right-wing John Birch Society and served as Agriculture secretary under President Dwight Eisenhower, helped further push his fellow Mormons into the conservative camp.

A report by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life in January showed that about 74 percent of Mormons lean toward the Republican Party and 66 percent of them call themselves conservative.

"Clearly, the Republican Party has taken the mantle of religious freedom and that bodes well for Mormons," says Rep. Jason Chaffetz, a Utah Republican who converted to the Mormon faith and the GOP.

"Principles of the Republican Party align with what Mormons believe," the congressman added, though he quickly noted that there are many Democrats who are also devout Mormons.

While the bond between Republicans and Mormons has grown, there remains a significant segment of GOP voters — mainly Protestant evangelicals like Southern Baptists — that has reservations about voting for a Mormon candidate.

Romney tried to tackle that concern head-on in his previous bid for the White House, offering a major 2007 speech in which he said no one should be elected, or rejected, because of his or her faith. He also said that, if elected, the LDS Church would not hold sway over his decisions in the White House.

"Let me assure you," Romney said, "that no authorities of my church, or of any other church for that matter, will ever exert influence on presidential decisions."

LDS Church leaders in the past clearly picked sides between Republicans and Democrats. But they now stress the church's nonpartisan stance and reiterate every campaign season that the faith does not back one party over another — even in the case of a candidate or platform in disagreement with a public position of the faith.

"Principles compatible with the gospel may be found in the platforms of the various political parties," LDS Church President Thomas S. Monson and his counselors said in a recent letter urging Utahns to attend neighborhood caucus meetings.

That statement is made possible by the fact that the phrase "twin relics of barbarism" appears nowhere in the major party platforms.

Editor's note • About this series

This story is part of an occasional series on Mormonism and its intersection with politics — a subject The Tribune believes is topical given the high-profile presidential candidacy of Mitt Romney, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.