This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Heber City • Brian Felsch rattles off commands to his science class at Wasatch High.

"Close your books. Close your notes. Close your mouths," he barks.

Notebooks slam. Backpacks zip shut. Students' pencils are poised for a second chance. Felsch is giving them a redo on a nitrogen-cycle quiz, calling out the questions as students scribble their answers.

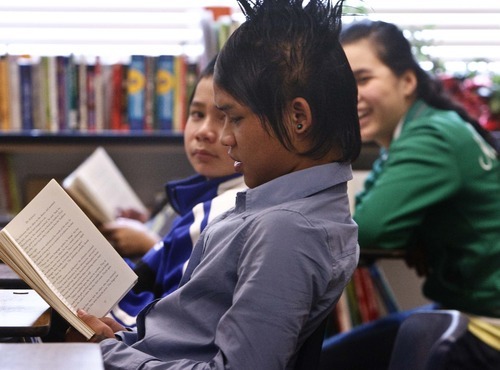

But one teen sits quietly in the back of the room with his textbook open. KaPaw Htoo, a junior, will take a different test — one that doesn't require words.

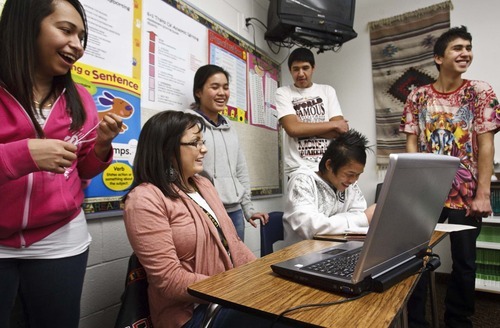

The 16-year-old KaPaw Htoo, widely believed to be the first refugee to attend Wasatch High, still speaks very little English. His family, ethnic Karens who fled violence in Burma decades ago, moved from a Thai refugee camp to Utah last summer. They settled in the Salt Lake Valley, where KaPaw Htoo (pronounced CAW-paw TOO) attended Cottonwood High. But in October, his father landed a job as a presser at Park City Dry Cleaning and Linen, a Heber business that has hired about 20 Burmese refugees,and KaPaw Htoo's family moved to the small rural town a month later. Heber's budding refugee community is nearing 60, including a number of children attending Wasatch district schools. Since January, two more Karen teens have joined KaPaw Htoo at Wasatch High.

"It's a new experience for us, for sure. Most of our English language learners are Spanish speaking," says Vicci Gappmayer, Wasatch's director of student services. "It's been a new challenge. But we're always up for that."

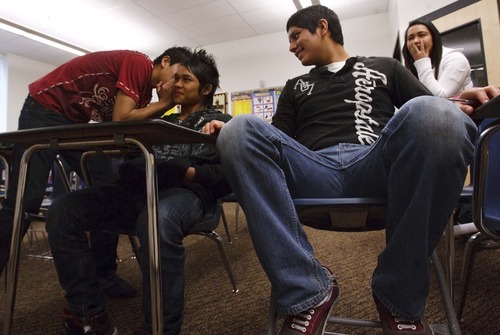

KaPaw Htoo seems unfazed by the change in schools. He says he likes his teachers, although when asked about his favorites, he gives room numbers: He doesn't know their names. At lunch time, he joins a raucous game of soccer but doesn't speak to the other boys. In an interview conducted through a Karen interpreter, he says he wants to try out for the soccer team. But a few days later, he says he's not going to the try-outs, offering no explanation. He's quiet in class unless called upon to read out loud. And then his voice is almost too soft to hear.

But he's ever mindful of his biggest challenge.

"Language is the barrier I have living here," he says through the interpreter. "If I can read and write fluently, then I won't have any problems living here."

Utah schools use a variety of "research-based" methods to reach the state's 45,000 students who are not fluent in English, says Rita Brock, the State Office of Education's English-as-a-Second Language (ESL) specialist. Some in San Juan and Tooele counties teach English with an eye to preserving American Indian students' indigenous languages. Others use dual-immersion programs in elementary schools to give students a bilingual education in English and in Spanish, French, German, Arabic or Chinese. Most schools that teach students who speak a variety of languages use "sheltered instruction," teaching the English language and academic content in an all-English setting. This model relies heavily on visual cues, including illustrations and gestures, to communicate.

Refugees, who are legal immigrants fleeing violence in their home countries, often pose additional challenges for schools. Children may have received limited schooling in refugee camps and need help adjusting to a new culture.

—

Lessons from Logan • Three years ago, Logan School District grappled with a sudden influx of Burmese refugees who moved to Logan from Salt Lake City to work at the JBS meat-packing plant in Hyrum. Refugees from many nations are typically resettled in Salt Lake City and assigned a caseworker for their first two years in Utah.

Most arrived with almost no material possessions, says Katie Jensen, co-director of the nonprofit English Language Center in Logan. But the community rallied to gather blankets, clothing, housewares and furniture. The language center offered an adult English class at the apartment complex where the refugees live.

"The pluses of coming to a community like this is the area is easier for [refugees] to navigate. It's more of a rural setting, which mirrors a little bit how they lived before arriving in the United States," Jensen says. "But no rural area is going to have all of the resources that an urban area like Salt Lake City has."

But Jensen believes Logan is now better prepared to help refugees.

In the past year, the city gained a refugee community council and a Utah Department of Workforce Services refugee liaison, who helps connect refugees to food stamps and other financial assistance they may qualify for. The Logan school district, which has 60 refugee students, has reached out to parents, coaching them on how to read the school calendar, offering tutors at parent-teacher conferences and organizing family field trips in which parents and students ride the public bus together to get to the library or a book store, says ESL specialist Janiece Edgington. Mount Logan Middle School is organizing a "cane ball" club so students can play the game common in Burma and Thai refugee camps. It's similar to hacky sack but involves a ball woven from cane or synthetic materials.

"Hopefully, we'll see other students [outside of the Burmese community] wanting to try it," Edgington says. "What we do is provide opportunities for students to integrate but not force it."

—

The bug connection • Heber, too, has welcomed the Burmese refugees, most of whom speak the Karen language, says Briton Wright, who has helped connect the Heber refugees with jobs and enroll their children in school. Wasatch district has offered a free adult ESL class, four days a week, at the apartment complex where the families live. At Christmas time, many Heber residents provided sub-for-Santa gifts to the refugee families, including KaPaw Htoo's family.

"I think they love us," the teen says in Karen when asked about his Christmas gifts — a soccer ball, socks and clothes.

At Wasatch High, the faculty has had to be nimble in crafting an academic plan for KaPaw Htoo. He spends five of eight class periods in English instruction or "content support," a study hall for English learners where they get help with assignments in other classes. Initially, he was enrolled in the school's most basic math class, Algebra I. But he was removed from that class after teachers realized KaPaw Htoo was too far behind. In Thailand, he never completed third grade.

Now, he spends one of his two study halls learning math with Luann Brandt, a Spanish teacher who also works with English learners. She uses a colorful, oversized math workbook for second-graders that features illustrations that can be readily understood. She emphasizes the vocabulary of math while teaching concepts such as how numbers may be "greater than" or "less than" one another. KaPaw Htoo practices counting by odd and even numbers and by multiples of five.

"The teacher will explain to me one time, and then I can do it," KaPaw Htoo says confidently in Karen.

His English vocabulary is growing slowly. English teacher Brent Price estimates that KaPaw Htoo knows about 300 words. His reading comprehension is similar to a kindergartner's, but he's starting to string together simple sentences. In one classroom assignment, KaPaw Htoo writes 10 sentences, ranging from "I play ball," to "Luis has new shoes."

"When I first came [to] Salt Lake, it was very hard for me," KaPaw Htoo says in Karen. "But now, most of the time, I can understand what the teachers say. The harder part is … for me to reply, to answer."

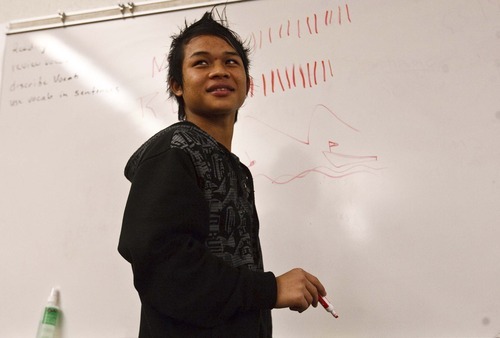

His other classes are art, desktop publishing and science. In Felsch's science class, Wendy Sharp, aninstructional aide, sits in the back of the class quietly working with KaPaw Htoo and two Spanish-speaking students. As Felsch lectures students about the nitrogen cycle, KaPaw Htoo studies a diagram in his text book. His test will be whether he can use pictures and arrows to draw nitrogen's cycle from plants to animals to the soil.

Sharp explains how bugs eat a dead pig, breaking down its body and returning nitrogen to the soil. KaPaw Htoo surprises her by telling her he ate bugs in Thailand — specifically, spiders. He would catch spiders, mice and snakes and fry them to supplement the family's camp rations. Moo Eh Htoo, a Karen student who has lived in Utah for four years, helps explain what KaPaw Htoo is saying. (The two are not related. In Karen culture, families do not share surnames; rather, they treat their entire name as a first name.)

—

KaPaw Htoo's dream • Meeting the testing goals set by No Child Left Behind poses a special challenge for teachers working with students like KaPaw Htoo who are learning English. Students get to skip state exams the first year they are learning the language, but after that they are held to the same standards as native English speakers. Utah, like most states, is seeking a waiver from the law, which requires all students to be proficient in reading and math by 2014.

In Utah, 35 percent of English learners scored proficient in language arts last year, compared with 85 percent of students who were fluent in English. The disparity was similar in math: 29.7 percent versus 71 percent.

Felsch says studying to get his ESL endorsement has helped him understand how to simplify science lessons and assignments for KaPaw Htoo.

"I can still do things with pictures and demonstrations, and he can still learn," Felsch says.

Increasingly, Utah school districts require new hires to have the ESL endorsement and encourage experienced teachers to get the training. This year, Wasatch High has offered the training on site through a partnership with Brigham Young University.

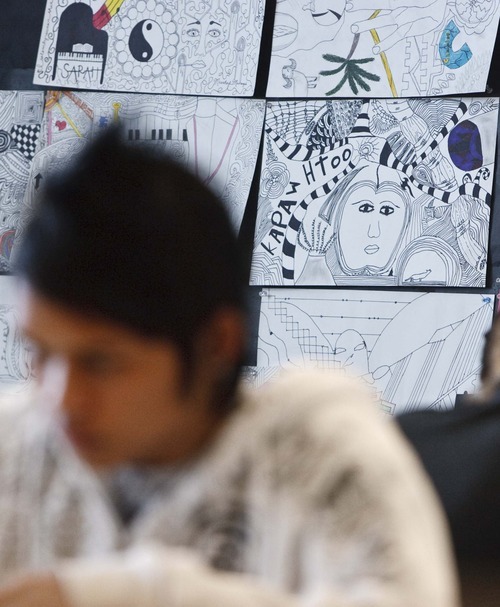

Elizabeth Sprackland, KaPaw Htoo's art teacher, also is seeking the endorsement, which teachers often say improves instruction for all students — not just English learners.

"I knew I needed it to be a better teacher," Sprackland says.

KaPaw Htoo hopes to finish high school and go on to college. He says his dream is to be a doctor. But he needs to earn 28 credits to graduate from Wasatch High, and he's at least two years behind because he entered high school as a junior with no credits.

Last year, 76 percent of Utah students graduated from high school. The rate for English learners was far lower: 45 percent.

Claire Mair, Wasatch district's adult education coordinator, says KaPaw Htoo can continue to earn credits toward a diploma, for free, in the adult program after his class graduates in 2013.

"He will be taken care of as long as he's in this community," she says. "If we can get him to come [to school], we can get him to graduate."

rwinters@sltrib.com Burma led by regime since 1962

Burma, also known as Myanmar, has been governed by an authoritarian military regime, in one form or another, since 1962, although elections in 2010 sparked hope of reforms.

In the past, the government has suppressed movements for democracy, killing more than 1,000 demonstrators in 1988. There also has been ongoing ethnic conflicts between the predominant Burmans and minority groups such as Karen, Karenni, Chin and others. Burmese authorities have repeatedly violated human rights, including "extrajudicial killings, disappearances, rape, torture and incommunicado detentions," according to the U.S. Department of State.

More than 2 million people, many of them ethnic minorities, have fled Burma to Thailand, Bangladesh, India, China, Indonesia, Malaysia and other nations, the department reports. In the past decade, more than a thousand refugees from Burma and Thailand have been resettled in Utah.

Source » Associated Press and U.S. Department of State, "Background Note: Burma," Aug. 3, 2011. —

Meet KaPaw Htoo

R The Salt Lake Tribune is documenting the journey of KaPaw Htoo, 16, as he copes with his first year of high school in Utah. In the second of an ongoing series, he adjusts to life in rural Utah and makes slow progress in learning English. Read the first part of the series • http://www.sltrib.com.