This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Kimberly Butler agonized over which medical specialty to choose, though, looking back, the decision was obvious, even inevitable.

"I liked every rotation. After psychiatry I thought, 'I definitely want to be a psychiatrist.' Then it was, 'Nope, I definitely want t o be a surgeon,' " said the fourth-year University of Utah medical student. "Finally, I sat down with someone I respect and said, 'Tell me why I shouldn't do family medicine.' She said, 'Kim, these are your people. This is where you belong.' "

More graduating medical students are coming to the same conclusion, applying in greater numbers for traditionally harder-to-fill residencies in family and internal medicine and pediatrics.

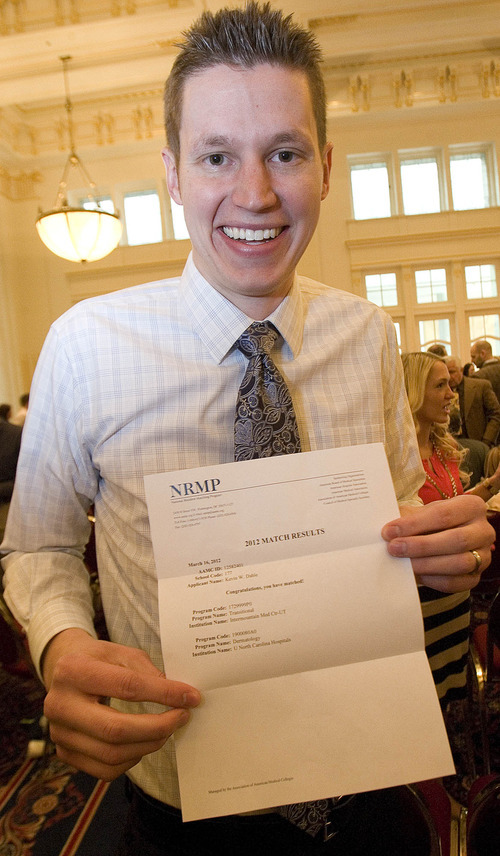

On Friday — known as Match Day — Butler and students across the country ripped open envelopes and learned where the National Resident Matching Program is sending them to train. At the U., 37 of the 97 graduates will serve residencies in primary care.

"It's unreal. I feel like I'm dreaming," said Butler, seconds after discovering she's headed to her first pick, Contra Costa Medical Center in California. "I expect this year to be pretty intense. I won't sleep a lot or eat well or exercise. ... I'm ready for it, whatever it brings."

Once seen as the R.O.A.D. to success, the higher-pay, lower-stress specialties of radiology, opthamology, anesthesiology and dermatology are no longer a sure bet, as prestige and power shift to primary care doctors, the country's best hope for improved health and lower costs.

"They're being called on to rescue us. It's like, 'Hey, Mighty Mouse we need you,' " said Phillip Miller, vice president of communications at one of the largest physician recruiting firms, Merritt Hawkins.

Experts predict a shortage of 90,000 to 200,000 physicians over the next 15 years, fueled in part by an aging population and influx of 30 million newly insured Americans under federal health reform.

But flat insurance payments, growing overhead and mounting regulatory burdens also play a role.

"There's a lot of angst and dissatisfaction out there," said Miller, citing a 2011 Merritt Hawkins poll of 10,000 first-year residents that found 29 percent would choose a career other than medicine if they could start over.

U. senior Kevin Dahle, who will do a dermatology residency at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said he cares less for earning potential than for quality of life.

"People don't realize what it takes to become a doctor. You can make a heck of a lot more money doing a heck of a lot less," he said. "You have to love it. There are so many doctors you talk to who are miserable just because they chose something for the lifestyle."

Dahle always knew he wanted to specialize because he likes knowing a lot about a single subject. He explored orthopedics and pediatric cardiology, following the lead of mentors who treated him as a teenager for rheumatic fever, but fell in love with dermatology.

The 27-year-old came to the U. straight after finishing undergraduate studies at Brigham Young University. He married his first year in medical school and has a 6-month-old daughter.

In applying for residencies, he looked for family-friendly locales, among other things. "There was no way I was going to pick up and move to New York," he said. Dahle would ultimately like to return to Utah, but doesn't know if he'll open his own practice or sign on with a hospital for set hours and set vacations — an increasingly popular path, especially for women.

For others, though, money is still part of the equation.

"Did I think about maximizing my income? A little," said Cory Kogelschatz, a 28-year-old with a wife, two young kids and a $150,000 student loan. "But in any field you can pay off your loans."

The California native and BYU alumnus will be trained in neurology at the prestigious Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and has hopes of working at an academic center.

Recognizing the financial demand on students, President Barack Obama's health overhaul includes a 10 percent pay hike for family practitioners seeing Medicare patients, a lead private insurers typically follow. And medical schools are tweaking their curricula.

"Our goal is to have all our students fluent in primary care," said Wayne Samuelson, associate dean of admissions at the U.'s School of Medicine.

Students used to spend their first two years hitting the books, but they are now immediately assigned to clinic rotations with a requirement that they spend time in a community clinic.

The Class of 2012 is the last to be taught under the old model. But the U. consistently fields a good crop of primary care docs — 41 of 102 graduates last year. "Future years will show whether that improves," said Samuelson.

Butler is "excited" about the direction that family medicine is headed, believing "it makes a lot of sense to put resources into caring for people before they get sick."

But still insulated from politics, she admits, "I have no idea what I'm in for, I'm sure. Doctors I work with here at the U. are on the cutting edge of change in health care, and even they don't know what to expect."

The Salt Lake City native wanted to be a doctor as a little kid, captivated by "the magic," she says, "of listening to people and finding solutions for them."

But it took some soul-searching and prodding from friends to convince her that medical school was within reach. She didn't come from a medical family or family of means. Her mom, a teacher, was the sole provider for her and her four brothers.

And there were competing interests. Butler played college basketball and had hopes of going pro until she was sidelined by a knee injury her sophomore year.

"It made me rethink everything. I just did a restart and started traveling," she said.

Butler spent three years overseas, teaching English in China, bar-tending in Turkey and working as a nanny in Belgium. "I met a lot of people who didn't have much," she said.

After returning to Salt Lake, she volunteered at a downtown clinic for the uninsured and homeless. She put her massage therapy degree to work and toyed with becoming a nurse or physician's assistant. "But I met some medical students who helped me realize it was possible to become a doctor. I wanted to do international work and thought being an MD would open more doors," said the now-36-year-old.

As if to test her resolve, she crashed her bike the first week of school, breaking her jaw in three places.

"I remember that day because I was on cloud nine. I was thinking about how I was going to study hard and do well," she said. "It definitely added a layer of complexity."

But her classmates rallied, taking notes for her and sharing their study guides. And she says the upside to having her jaw wired shut for two months was, "I didn't have to plan meals."

Butler wants to work with underserved populations, whether at a community clinic or in foreign country.

"One of the happiest times in my life was when I was in Europe and Asia with nothing but the clothes on my back. I was so ridiculously poor. Why would money make me happy?" she said. "The great thing about family medicine is I can do a little bit of everything, and if decide later that I want to narrow my practice to women's health or geriatrics, I can still do that." —

All the U.'s medical students matched

Every year in March, the National Resident Matching Program places graduating medical students in residencies where they train in their chosen specialty. Students interview at their favorites and rank them. Residencies also submit their top picks, and a computer matches them.

Results arrive in an envelope on "Match Day."

At the University of Utah:

97 students matched — 35 women and 62 men — with 60 programs in 19 different specialties.

37 students went into primary care

30 students will be staying in Utah for part or all of their residency training

The rest will head to 28 different states to train.