This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

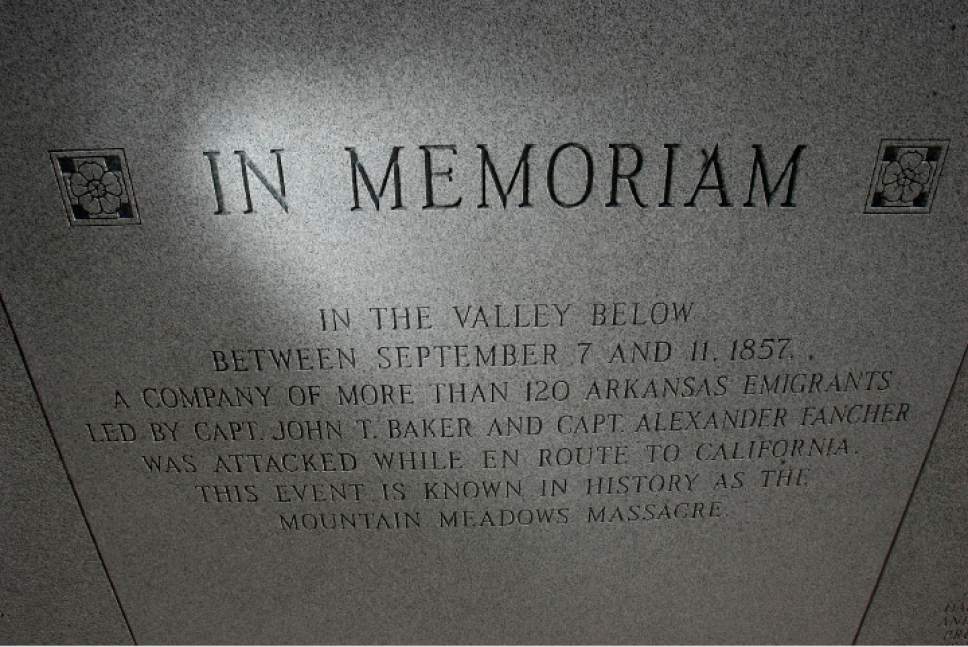

U.S. soldiers investigating the 1857 massacre at Mountain Meadows found the remains of 120 westbound pioneers scattered about the killing fields north of St. George, where Mormon marauders had attacked California-bound immigrants in an act of violence and deceit that still stings more than a century and a half later.

Among the uncounted human bones they gathered for burial on-site was a skull that expedition members removed as crime-scene evidence and forwarded to what is now known as the National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM), established during the Civil War to promote understanding of military medicine.

Soon the remains will be headed back to Utah for permanent interment with the others slain by pioneer men from Parowan after a five-day siege.

The skull, which analysis shows belonged to a child killed by gunshot to the back of the head, will be laid to rest this summer at Mountain Meadows during a ceremony marking the massacre's 160th anniversary. It will be joined with soil brought from the child's native northwest Arkansas and in a small box crafted out of an oak tree from the Ozarks, according to Patty Norris, who heads one of three victim descendant groups involved.

"None of these children [killed at Mountain Meadows] had a Christian burial. They never had anything. We are going to have a beautiful service. We are going to have prayer, we are going to have songs. It will be done by the descendants. The [LDS] Church will furnish a tent and, at the end, we will have beautiful music. Family members will line the pathway to the monument where the vault is. They will be able to say goodbye. It will be a big deal and a little bit of closure," said Norris, president of the Mountain Meadows Massacre Descendants and great-granddaughter of survivor Tryphenia Fancher.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints maintains the monument at the massacre site and works with the descendants to honor the victims at events like the one scheduled Sept. 9, when the child's remains are to be interred.

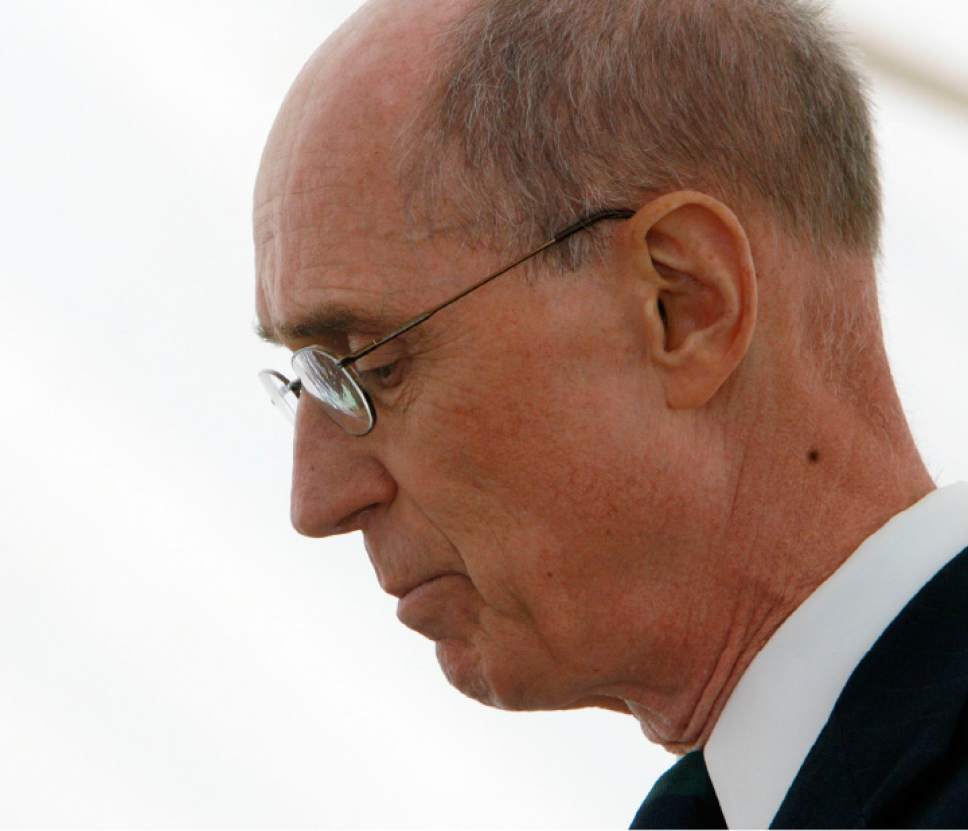

"It is our obligation to understand and learn from the past," said Mormon historian Richard Turley, who co-wrote the acclaimed 2011 book "Massacre at Mountain Meadows." "No one living today had anything to do with the atrocity, but we are responsible for how we deal with the subject today. It is important that we are honest and straightforward and learn from the past."

—

Competing claims • Although all three main descendant groups endorse the skull's return to Utah, some individuals with roots dating to the Baker-Fancher wagon train insist it should be DNA-tested to determine to whom of the massacre's 20 child victims it belonged. Identifying the child will allow his or her living relatives to choose where the remains should be buried, according to Catherine Baker of Bryson City, N.C.

"We believe the decision should be a familial one and not made by any one descendant group. If it's a Dunlap, the decision should be made by that family," said Baker, who adds that she speaks for 200 descendants.

The skull's existence at the Maryland museum apparently came to light in the 1990s, and the descendant groups and Baker initiated competing efforts to claim it for burial. Museum officials could not determine who had a "superior" case, so last year they announced in the Federal Register it would not be released to any one group. Returning it to the massacre site for interment is an "equitable, ethical, respectful resolution," the museum concluded.

This decision did not sit well with Baker, who enlisted the help of two U.S. senators, Richard Burr of North Carolina and Martin Heinrich of New Mexico. In response to the senators' inquiries, military officials said identifying the child's next of kin is not possible.

"The pool of appropriate candidates for DNA comparison are [sic] insufficient to achieve conclusory findings because the remains are unidentified and may belong to one of several families and because the 1857 massacre took the lives of the child's closest relatives. Therefore, DNA analysis will be destructive to the skull and will likely result in inconclusive findings," Rear Adm. Colin Chinn, research director of the Defense Health Agency, wrote to the senators.

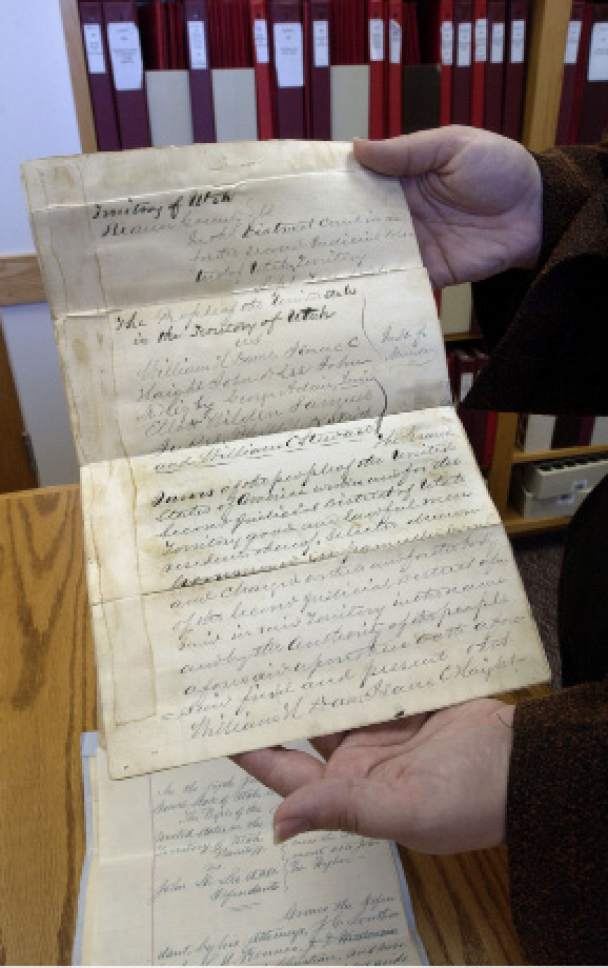

Acting on behalf of Randall Baker, a direct descendant of survivor William Baker, Catherine had brought a claim under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) on grounds that the Bakers had Cherokee blood. Four Baker children, including an adoptive son, died at Mountain Meadows with their parents. But Chinn wrote that this assertion was tenuous, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee had declined to press its own NAGPRA claim. Baker contends the museum failed to investigate her case and that the tribe never was consulted.

—

Speedy burials • The massacre of Sept. 11, 1857, was preceded by a prolonged siege of the Fancher-Baker wagon train by Mormons angry with the immigrants over gestures of disrespect as the immigrants passed through the Utah territory. In a deadly double cross, Mormon militiamen persuaded the embattled immigrants to surrender with a phony promise of safe passage. The weary immigrants were led away to the north and split into two groups, the men going in one direction and the women and young children toward another. At a predetermined signal the killing began.

Nearly two years later, Maj. James Carleton led an expedition to investigate the sad fate of the Baker-Fancher train and put the victims' remains in the ground. There had been attempts at hasty burials, according to Turley, the historian who now heads the LDS Church's Public Affairs Department.

"Eventually, the partial burials were disinterred by animals, and before long you had remains scattered for a distance of up to a mile. There were skulls and other bones lying on the surface," Turley said. According to Carleton's account, his 200 men gathered these remains and put them in rock tombs, but for years the locations remained unknown.

Two years ago, archaeologist Everett Bassett identified two rock mounds he believes are these "sepulchers," but no one is eager to dig into them to find out for sure what lies beneath the basaltic rocks that clearly had been transported to the site from somewhere else.

Turley said it was military practice at the time to collect human remains from a battlefield.

According to the museum's register posting, Carleton's soldiers delivered the skull to Army surgeon B.A. Clements, who forwarded it to Washington to what was the Army Medical Museum, in 1864. Subsequent analysis of the teeth indicated the child was between 6 and 10 at the time of death, which is too young to determine its gender from a skull.

The military-run museum later changed its name to the National Museum of Health and Medicine and was housed at Walter Reed Army Medical Center until it moved to its current Silver Spring home in 2011. While it is one of the few museums that display human remains and tissue specimens, there is no record the Mountain Meadows skull was ever on display, according to spokesman Tim Clarke. He did not share a photograph of it or provide any details about how it was handled and stored over the century and a half it has been in the care of the museum, which has changed locations a number of times.

—

Remembering the victims • This summer, the museum's anatomical curator, Brian Spatola, will personally escort the Mountain Meadows remains to a St. George funeral home, where it will be enshrouded in a quilt made by descendants and encased in the special casket made from Arkansas oak. On Sept. 9, Spatola is to bring the box to the historic monument, where the massacre's anniversary observances will include a funeral that memorializes all the children who perished.

According to historians, the militiamen killed these youngsters to ensure they wouldn't bear witness to the crime, which proved to be the worst atrocity suffered by Americans at the hands of countrymen until it was eclipsed by the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Seventeen children under 6 were spared; some were raised in Mormon homes.

By Catherine Baker's tally, the list of possible victims includes 12 children from four families: three Fanchers, three Bakers, three Dunlaps and two Huffs, as well as the Bakers' adopted son, David Beller.

Baker wants to know if the skull belonged to Mary Lovina Baker, whose three younger siblings — William, Martha and Sarah — survived the attack. Seven-year-old Vina, as she was called, protected them during the ordeal leading to the massacre. Granddaughters to sisters Martha and Sarah have joined Baker's call for DNA testing. Relatives would like the skull to be buried with Martha back home in Arkansas if it belonged to Vina.

"The child was a victim of murder. Placing the child in an unmarked grave would victimize the child again," Judy Gladden, Sarah's granddaughter, wrote in a Feb. 7 letter to the museum. "We, as a society, make every attempt to identify unknown murder victims. This child should be afforded the same respect."

Other descendants believe DNA won't prove the cranium is Vina's because many of the slain children were close relatives to one another and died with both parents.

"It's an interesting story, but how can you prove that's who it is, especially when there were cousins on that wagon train?" said Phil Bolinger, president of the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation. "Each family had so many children and some are first cousins, so when their parents are siblings and marrying each other, many kids may fit the match. At best, you might find out which family he was related to. It's a lot of effort. The best thing to do is to bury it at the rightful place, which at this time is with the immediate family."

Baker counters that DNA testing is worth the effort, and she has gone to great lengths lining up possible descendants to provide DNA samples.

"If a compromise cannot be reached, we have the option of filing an injunction in the federal courts, which could drag out for years and prove to be very expensive," she wrote in an email.

Patty Norris noted the child's remains are to be treated with the utmost respect and will not be interred anonymously, but in a vault as all the child victims, including Vina Baker, are announced by name and age.

"I don't know what else we could do," Norris said. "Nothing about Mountain Meadows is simple, and this certainly isn't."

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Brian Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713.

Twitter: @brianmaffly

Correction: June 24, 4:55 p.m. • An earlier version of this story misstated the date of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. —

The lone conviction

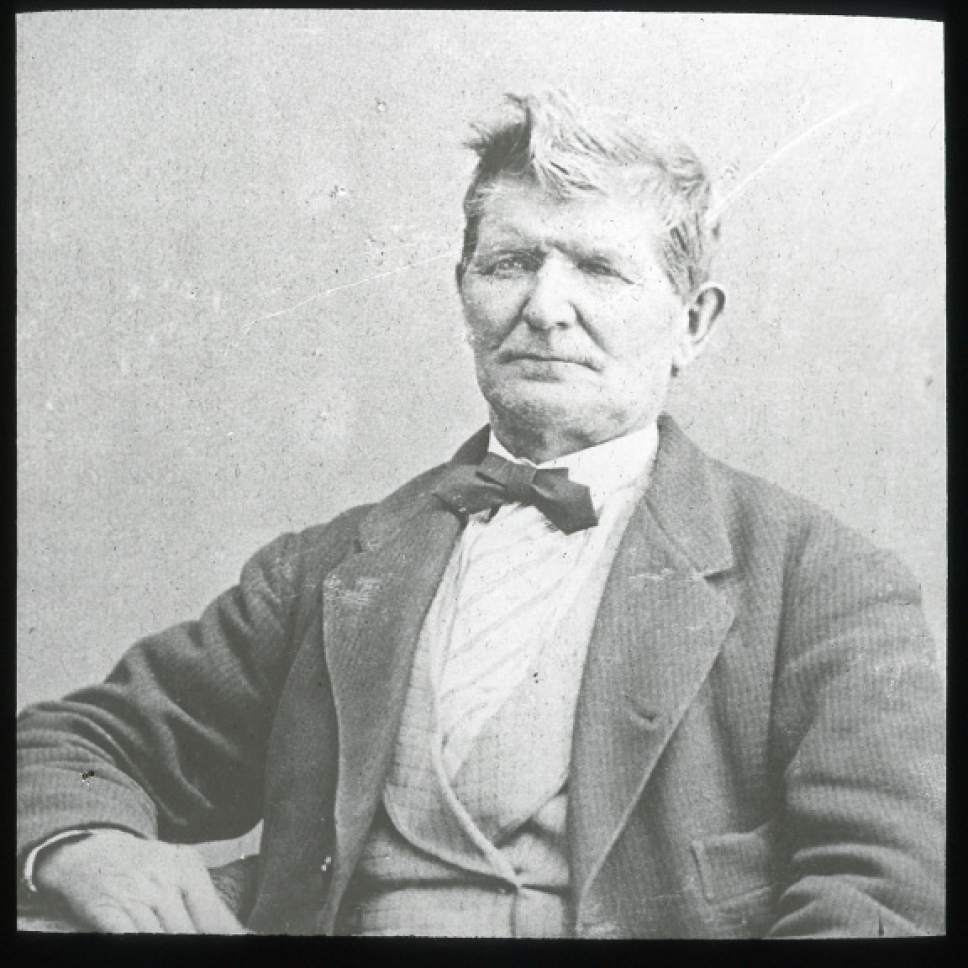

John D. Lee, an adopted son of then-Mormon prophet Brigham Young, is the only person ever convicted and executed for his part in the Sept. 11, 1857, slaughter of 120 men, women and children at Mountain Meadows.

The slain immigrants, part of the Baker-Fancher wagon train, were bound for California.

Shortly after the Mountain Meadows Massacre, Lee was arrested at Fort Harmony.

He was tried in Beaver and acquitted by a jury. Two decades later, Lee was tried again in Beaver, but this time was found guilty and sentenced to death.

On March 23, 1877, the sentence was carried out at the massacre site. Lee asked members of the firing squad to aim at a paper target in the shape of a heart he had pinned on his coat while he sat on his open casket.

Lee is buried in Panguitch.

The horrific attack incites debate to this day about Lee's involvement and whether he was acting on Young's orders.