This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Ron Stallworth found himself in the middle of a cultural debate surrounding rap music in 1996, when the east coast-west coast rap feud, as it was known, reached new heights with the fatal shooting of star Tupac Shakur outside a Las Vegas nightclub.

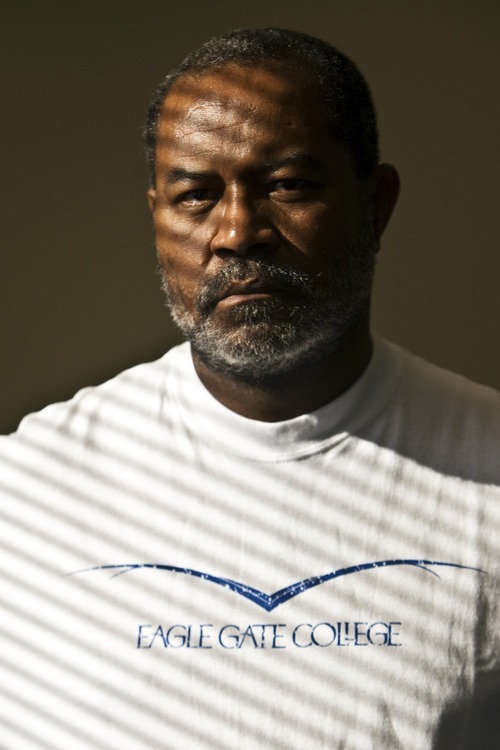

Stallworth, who helped launched Utah's original Metro Gang Unit and today serves on Mayor Ralph Becker's Salt Lake City Gang Reduction Steering Committee, had studied rap lyrics and their meaning long before the death of Shakur, which was followed in 1997 by the slaying of the hip-hop mogul's rival, Notorius B.I.G., in a drive-by shooting.

So when ABC's "Primetime" called Stallworth to appear on national television in the wake of Shakur's death to weigh in on the role of rap music in violent crime, he naturally fit the role. The show's main question: Did Stallworth think gangsta rap music led to Shakur's death?

"I told them no and I told them why," recalled Stallworth, who is now retired, but works part-time teaching courses at Salt Lake Community College as well as serving as Davis County's gang intelligence consultant. But he wasn't satisfied with time he was given to explain himself on TV.

After Stallworth boarded a plane home to Salt Lake City following the interview, he pulled out a pen and paper to jot down questions he'd been asked and began crafting answers to them.

Fifteen years later, Stallworth has taken what began has brainstorming session in the sky and turned his research into two newly published books.

The first, Bringing the Noise: Gangster-Reality Rap and the Dynamics of Black Social Revolution, explores gang culture through the lyrics and music of gangsta rap. The second, Gangsta Code, explores Shakur's death and issues that arose in the rap community as a result.

Both books remain relevant today, said Stallworth, who is targeting an audience of police officers, educators and kids with the material. Today's rap artists are doing what their predecessors did with music: agitating the system, or government, with lyrics that express their discontent over their places in society, Stallworth said.

In Bringing the Noise, Stallworth explores the history of music as a way to rebellion, starting with what he deems may be one of the earliest gangsta rap songs penned — "The Star-Spangled Banner."

"It was a song meant to inspire us; to unite us as a people and to agitate the system at that time against the injustices of the British population," Stallworth said.

"That was a gangsta song by today's standards, but it's our national anthem too," he said. "[Gangsta rap] really isn't anything new, it's just how they are saying it."

Stallworth hopes that with such an understanding, police will think more critically when encountering people who are seemingly hostile toward law enforcement.

His research into rap over the years led him to knock on the doors of several prominent stars, including Ice Cube, whose song "F—- Tha Police" performed with group N.W.A., rattled the cages of law enforcement across the country.

Stallworth approached Ice Cube backstage after a 1993 performance at Salt Lake City's fairgrounds. He explained to the rapper that he was studying gangsta rap and wanted to better understand the motives behind Ice Cube's lyrics.

Ice Cube invited Stallworth in and the two discussed music over a bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken, Stallworth recalled. The conversation led to an important insight. Ice Cube acknowledged to Stallworth that he realized there were some good cops on the streets. But most of Ice Cube's friends in Los Angeles had been unfairly targeted by police, and the song was Ice Cube's protest.

"[Rappers] are using lyrics to attack police for attacking them. In their music, they're describing why they feel the system needs to be agitated," Stallworth said.

"Is he saying f—- the police because the police were caught committing an illegal act and this is his protest response? That is a legitimate response, whether we like it or not. We need to look deeply into the music to ask how can we fix the inspiration behind it. The whole purpose of the song was to give a voice to people that are voiceless."

Stallworth went on to testify before Congress three times about the country's gang problem, in particular about how rap music plays a role in gang culture.

Ken Hansen, a detective with the Metro Gang Unit who worked gang cases with Stallworth in the early 1990s, said Stallworth's expertise will benefit educators who turn to his book to learn more about gang issues and how to deal with today's youth.

Hansen praised Stallworth for the amount of research he put into the books, not just in Utah, but in communities with gangs across the United States.

"If you look at the history of the gang problem here, in some ways it caught us by surprise," Hansen said. "Now is an opportune time to really focus on juvenile gang members to keep them from moving up the line to becoming full-fledged gang members."

Stallworth said he's hopeful his books can be of some help to those who read them. He recalled starting the projects as a guide to help him understand what he was seeing on the job, but he is happy it has turned into a broader endeavor.

"I didn't write this for anyone's benefit but my own when I started," Stallworth said. "I started studying the music kids were listening to, and it ultimately led to me writing about it."

Twitter: @mrogers_trib —

Author touts impressive resume in policing, researching gangs

Some highlights of Stallworth's career include:

Testified before Congress three times about the country's gang problem, in particular how rap music plays a role in gang culture.

Works as an adjunct criminal instructor at Salt Lake Community College and Eagle Gate College in Layton.

2008-current • Co-chairs the Salt Lake City Gang Reduction Steering Committee, organized by Mayor Ralph Becker. The group is working to implement a nationally recognized "comprehensive gang model," which calls for grass-roots volunteer organizations, law enforcement and the courts to work together through a mix of programs and community activities to help gang-involved youth. The city is in the process of hiring gang outreach workers to implement the initiative.

1993-2000 • Served as gang intelligence coordinator for Utah, a position created for him by the Utah Public Safety Commissioner.

1992-2000 • Traveled across the country lecturing on street gang culture and gang mentality. Also authored four books.

1990 • Helped start what is today the Salt Lake Area Gang Project/Metro Gang Unit, the first multi-jurisdictional gang suppression unit in the state.

1987-1989 • Worked as an undercover investigator with the Narcotics and Liquor Law Enforcement Bureau with the Utah Department of Public Safety. He conducted research on the state's gangs, and his report led to the first gang task force in Utah, a joint venture between the Utah Division of Investigation and Salt Lake City Police Department.

1981 • Worked on investigating Los Angeles-based Crip and Blood gangs while serving as an agent with the Arizona Criminal Intelligence Systems Agency in Phoenix.

1979-1980 • Led an undercover investigation into the Ku Klux Klan, where he infiltrated the KKK's Colorado Spring chapter. He still carries a David Duke-signed KKK card in his wallet.

1978-1979 • Investigated outlaw motorcycle gangs while assigned to the intelligence unit of the Colorado Springs Police Department.

1998 • Received the Frederick Milton Thrasher Award from the National Gang Crime Research Center for outstanding contributions to scholarship, service and innovation in gang research. —

For more information:

Ron Stallworth's new books are available at http://www.policeandfirepublishing.com and will soon be available on http://www.amazon.com