This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

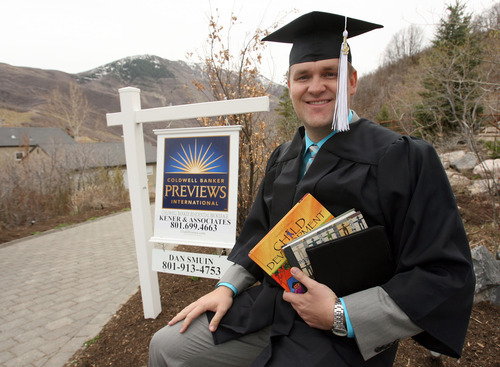

During a typical week, Realtor Dan Smuin drives all over the Salt Lake Valley showing homes, like a 5,000-square-foot place up Emigration Canyon with five bedrooms and lovely views of the path followed by 70,000 Zion-bound Mormon settlers a century and a half ago.

But he also spends up to 18 hours in a University of Utah classroom.

He doesn't get much sleep and doesn't socialize on campus, but he is almost finished with a degree in human development and family studies. Smuin will be among the 5,513 U. undergraduates receiving bachelor's degrees this year — eight years after he began his studies at Salt Lake Community College. He worked 40 to 60 hours a week the whole time and is completing college without a penny of student debt.

"It would have been nice to not work," said Smuin, who initially could not qualify for financial aid because of his parents' income.

Unsaddled with college loans, however, Smuin is fortunate.

U.S. student debt topped $1 trillion this year and surpassed the nation's consumer debt, triggering an outcry for relief and a stop to relentless tuition hikes.

By working long hours, Smuin and many other Utah college students are avoiding this burden. But campus administrators say that may not be a good thing if students are taking longer to graduate.

"A problem in Utah is we have a huge number of students working even though tuition is low," Commissioner of Higher Education William Sederburg said. "You're better off to go into debt and have a real college experience and not getting distracted on things that delay graduation."

—

Money well spent? • Some graduates, like the U.'s Amy Jensen, are left with unmanageable debt loads.

Jensen, 45, will graduate this spring with a degree in anthropology and $60,000 of student debt. She started borrowing when she began college more than 20 years ago, then bailed as the obligations of single motherhood became too much to balance with the rigors of higher learning. Her $25,000 in loans ballooned to $50,000 after years of payment deferrals and interest.

"It was a catch-22. There were many years that I said, 'I would never go back to school and get my degree. That's for people who have money and have privilege,' " she said. A few years ago, she took "the swan dive off a cliff" and returned to the U., taking out yet more loans after she was laid off last year.

"I decided that was money well spent and I'll figure out the consequences later," said Jensen, whose daughter graduated from Utah State University on scholarship without debt.

Last year, 145,000 students at Utah schools, including for-profits, took out $662 million in federal student loan programs administered under Title IV of the federal Higher Education Act, according to the Utah Higher Education Assistance Authority, or UHEAA. (This figure excludes Western Governors University, a Utah-based online school whose students accounted for another $200 million in federal loans that appear in Utah's data. The majority of WGU students have no connection to Utah.)

Utah students' annual loan volume is close to what the state spends on higher education. Nationally, the U.S. Department of Education issued about $97 billion in loans in 2009-10.

—

Last in debt • For student borrowers attending traditional four-year colleges or universities, average debt is $25,250 for 2010 graduates, according to the Project on Student Debt's most recent annual report. Utah's average was $15,509, the nation's lowest.

"A moderate amount of federal student loans to enroll and complete in higher education can be a very good investment," said the report's author, Matthew Reed, a researcher with the Institute for College Access and Success. "You earn more and have lower unemployment, but you have to complete the degree to get most of that benefit."

Utah is also at or near the bottom of states by these measures: the portion of students who graduate with debt (44 percent), default rates, and the so-called debt-to-degree ratio, calculated by the volume of debt taken on by a school's students divided by the number of degrees it awards in a given year.

States with the highest student debt are clustered in the Northeast and upper Midwest, while those with the lowest are in the West.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, Utah's two-year default rate is 2.2 percent, or a quarter of the national average, further evidence that student debt is not nearing a crisis in the Beehive State.

Sederburg cautioned that it would be unethical to encourage students who have little chance of success to take out loans. But for those completing degrees at traditional, regionally accredited schools, such as the U., SLCC or the higher-priced private Westminster College, taking on debt is likely a wise move. The question is how much.

"The confounding factor is what kind of degree and what are your job prospects?" Sederburg said. "People should individually make that calculation."

Experts say incomes upon graduation can vary depending on the major, and students should structure their borrowing accordingly.

—

Slow to graduate • Most Utah students may not be drowning in debt, but they also are not graduating as fast as administrators and policymakers would like.

According to a recent legislative audit, the U.'s six-year graduation rate is 58 percent, putting it near the bottom among Pac-12 institutions. The six-year rate at Brigham Young University, the U.'s more selective, LDS Church-owned rival in Provo, is 77 percent.

One likely reason for the U.'s relatively low completion rate is poor preparation among incoming students. To turn that around, administrators are raising admission standards and adopting a "holistic" approach in admission decisions. But they are also concerned that student employment is playing a role in lackluster graduation rates.

Only 18 percent don't have jobs, while about half work between 20 and 40 hours a week, according to a recent survey of U. undergraduates.

Those with large workloads not only take lighter course loads, but could also be undermining their academic performance. Part-time enrollment can be very costly to both students and taxpayers, officials say.

"If you postpone graduation, you forfeit the earning potential for those beginning years," said David Feitz, UHEAA's executive director. "But the bigger risk is not graduating at all. Life happens."

During his years as provost, now-U. President David Pershing sought to reserve campus jobs for students, to keep working students more connected to the university.

"Studies show those who work on campus are retained at a higher rate and graduate faster than those who work off campus," said Mary Parker, associate vice president for enrollment management.

On-campus engagement in other nonacademic activities — such as intramural sports, service-learning projects and student government — also correlates well with student success.

—

Laboring class • Fourth-year student Valerie Johnson, who is about to graduate with a degree in mass communication, has worked as a concessions supervisor at Pioneer Theatre Company and at the Olpin University Union information desk. Like most students who take campus jobs, she works no more than 20 hours a week.

"It keeps me close to campus. I can go to class and not have to worry about the [work] schedule," Johnson said. "And if you work on campus, they are more conscious of your [class] schedule."

Johnson attended the U. on scholarship for the first three years, but lost the aid her senior year after her grades dipped. To make up for the shortfall, she took out her first loans this year and expects to graduate with $5,000 in debt.

"I don't like being in debt, but I have to do what I have to do," Johnson said. "My goal is to pay it in five years. It makes me value my education more if I have to pay for it out of my pocket as opposed to someone else paying for it."

Honors student Ashley Edgette, who expects to graduate next year without debt, is funding her education through scholarships and off-campus employment related to her academic interests in food security.

"If you work two jobs, you can't do the cool things that stand out and allow you to do what you want to do," said Edgette, a political science major who reduced her costs by first earning an associate's degree at SLCC. Her community service at Salt Lake City's west-side schools caught the attention of the Harry S. Truman Scholarship Foundation, which this month awarded her $30,000 for graduate school.

Dan Smuin concedes that working took a toll on his grades, which are not good enough to guarantee admission into graduate school. But today, married without children, he is already two years into his career as a real-estate agent and exits school as the market is showing signs of life.

"If I didn't have school to worry about," he said, "my life would be a lot less stressful."

Read more: Primers on college debt

• Educational debt is spiraling — and some argue, becoming a drag on the nation's economy. A new study disagrees, but offers a cautionary note.

• Here are the three federal loan programs, which have expanded in the last decade.

• Saving ahead for college and securing scholarships once you are there help avoid debt. Here are Utah resources.