This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Turn-of-the-20th-century Utah would seem impossibly remote from the Titanic disaster in the North Atlantic. After all, how much resonance could a collision between an iceberg and the most opulent ship of its time have for a pioneer culture in the American desert?

Yet the fascination with the world's most famous ocean catastrophe stirred Utahns deeply, even though only one drowning victim proved to be from the state. And the 100th anniversary of the Titanic sinking seems a fitting time to revisit the extraordinary story of Irene Colvin Corbett, a Mormon woman who was always ahead of her time.

—

High-tech media frenzy • Within hours of the Titanic's encounter with an iceberg on Monday, April 15, 1912, Utah learned of the disaster through the then-high technology of radio communication. Much of the initial news was inaccurate, including reports the ship hadn't sunk and was being towed to port.

As details emerged, The Salt Lake Tribune, Deseret News and The Salt Lake Herald-Republican cleared their front pages. The story of the Titanic and its 1,513 victims and 711 survivors dominated Utah news for the remainder of April and through most of 1912.

As of Tuesday, April 16, no Utah passengers had been reported. In fact, the Herald-Republican reported that the grief of a Salt Lake City woman for her missionary son David Cummings, who she believed was aboard the Titanic, was "immediately turned to unalloyed joy" when Cummings walked through the door unannounced.

But by Wednesday, Salt Lake City papers were reporting the only direct Utah connection: "Provo Woman Among Missing; Family Hopeful," according to a The Herald Republican headline.

Thirty-year-old Irene Corbett's name didn't appear among those of the 710 rescued passengers, but as a woman traveling in second class, she would have had an almost guaranteed place in a lifeboat.

—

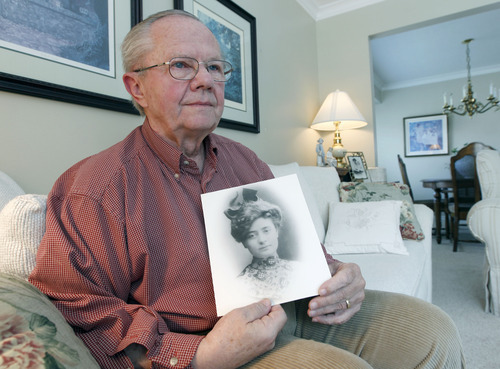

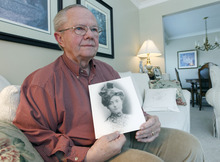

Before her time • Irene Colvin Corbett was an anomaly for a turn-of-the-20th-century Mormon woman, says her grandson, Don Corbett, of Bountiful. She was a former schoolteacher who later trained as a nurse, who was smart and ambitious, with feminist leanings.

"She believed that women had just as many rights as men and developed some connection with the suffragette movement," Don Corbett says. "That might have been one of the seeds that prompted her desire to grow and develop as a nurse."

Irene Colvin married Walter Corbett in her mid-20s, and in 1912, the couple had three children: Walter, 5; Kady Roene, 3; and Mack, 22 months. That's when she made up her mind to study midwife nursing at the General Lying-in Hospital in London.

Infant mortality was still high in Utah, and Irene was apparently a gifted nurse at a time when women physicians were rare. "Physicians in Provo encouraged her to study midwife nursing," Don Corbett says. "They needed as many skilled people as possible."

But Irene immediately ran into resistance from her husband and in-laws. Mack Corbett, Don's father, passed much of the family lore on to his son. "Irene told them London was the best place to study," Don Corbett says. "They tried as much as they could to persuade her not to go."

Husband Walter Corbett was unequivocal: "Don't go."

—

Against the grain • Undeterred, Irene decided to combine missionary work in London with her medical education. She traveled to Salt Lake City to get a blessing from Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Prophet Joseph F. Smith. Walter Corbett and his mother had appealed to Smith to forbid the trip.

"Grandma Irene didn't go to get the president's permission," Don Corbett points out. "She just wanted his blessing."

When Irene and her father, Levi Colvin, a Mormon bishop, met with Smith, the prophet didn't support Irene's desire. "He discouraged her. He said you should stay close to home [for training]. Go to Philadelphia or somewhere in the United States," Don Corbett says. "He was firm on that and would not give her a blessing."

Irene went anyway. Her parents mortgaged their farm to pay for the trip and the tuition, marking the significance of Irene's reverse journey of that of her grandmother, who immigrated to Utah from England as a pioneer. Her ancestor's sea journey was legend in the family for its danger and discomfort.

At this point, the story is picked up by Wallace Malmstrom, a Mormon missionary on his way to Norway, who struck up a friendship with Irene. Don Corbett was able to track down Malmstrom's journal. (Most of Irene's papers and letters were destroyed later by her sister in an attempt to ease her mother's grief.)

—

Harrowing journey •Travel in the early 20th century was dangerous. A blizzard in Wyoming stranded Irene's train for a day. When she boarded ship in Montreal for Quebec, it was delayed for days by thick November fog on the St. Lawrence River.

But worse was ahead on the Atlantic. The RMS Virginian was a small, single-funnel steamship, but equipped with the newest technology in steam turbines, which, unfortunately, made the ship roll and pitch under full power. About halfway across the Atlantic, the Virginian hit a winter storm, and the seas were so high that the captain was forced to turn the ship east so it could battle the huge waves bow first. Still, the ship's Marconi radio tower was knocked over and dishes smashed.

"The ship was tossed to and fro, back and forth. In the midst of this, Irene and [Elder Malmstrom] are the only ones not seasick," Don Corbett says. "They had long talks about Irene's decision to go to London. She was wondering if she did the right thing. She had disobeyed everyone, including the prophet."

The ship arrived in Liverpool three days late. "It was a harrowing trip and it had to play into her decision to return by the biggest ship afloat," Don Corbett says.

After a successful six months of training at the Laying-in Hospital, followed by long hours working among London's poor, Irene was ready to come home.

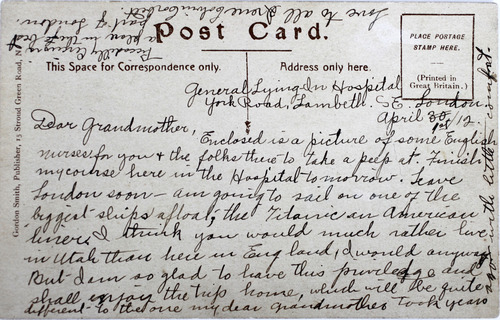

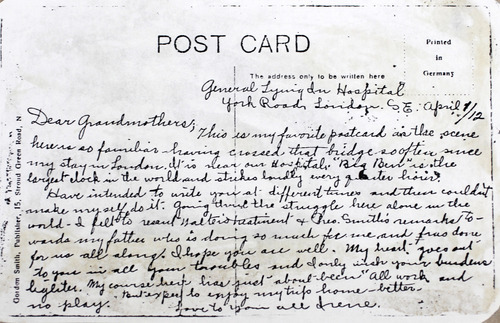

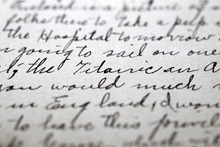

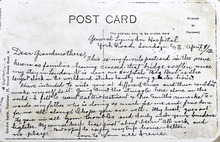

On a photo postcard of Piccadilly Circus that Don Corbett cherishes, Irene wrote home to her family:

"Leave London soon. Am going to sail by one of the biggest ships afloat, the Titanic. … I am so glad to have this privilege [to study in London] and shall enjoy the trip home, which will be quite different to the one my dear grandma took years ago with little comfort."

Don Corbett surmised that Irene chose to sail home on the Titanic because it would be an adventure to sail on the world's largest ocean liner and, probably, because the luxury ship on its maiden voyage was lauded as "unsinkable."

—

Lucky charms • The Titanic had another draw for Irene after the terrifying trip over on the Virginian: Six returning Mormon missionaries were booked aboard. Having missionaries aboard a ship was considered a good-luck talisman among church members — and even sea captains.

"Irene was excited to have missionaries making the trip with her," Don Corbett says. "According to all the accounts I can find, there were no deaths of missionaries while crossing the Atlantic."

But two days before departure, one of the missionaries was delayed in getting to Southampton. He wired ahead for his companions to leave without him, but the church official who made travel arrangements switched the missionaries to the Mauritania, scheduled to sail a day after the Titanic.

"When she realized they were not on board, it was very disturbing to her," Don Corbett says.

Probably unknown to Irene, also aboard was non-Mormon British crusading journalist and peace activist William T. Stead, who was considered a hero and a friend by the LDS Church. In a time of anti-Mormon hysteria in England, Stead had written powerfully in defense of the Utah-based church's right to proselytize. Stead was in first class on his way to a New York peace conference at the invitation of President William Taft.

Four days later, an iceberg ripped open the Titanic's steel hull, flooding five of 16 watertight compartments, and the unsinkable ship sank in 2 1/2 hours. Irene Corbett's and Stead's bodies were never recovered.

A century later, when Don Corbett recounts his ancestor's story, he talks about destiny — his grandmother's and the Titanic's. The ship was on its maiden voyage traveling at high speed on a moonless night through a glassy sea that made it difficult to see icebergs. Lookouts hadn't been issued binoculars. The ship didn't have enough lifeboats. Wireless communication was in its infancy, and Titanic radio operators broadcast the old distress signal CQD along with the newer SOS.

—

Waves of fate • Don Corbett says Irene's defiance of her in-laws and the Mormon prophet to go to England was later seen by some in the family as determining her fate.

"Is it because she didn't get the blessing?" Don Corbett says of the family's search for an explanation, especially when they learned of the six missionaries' narrow escape. "She went against the recommendation of the president of her church — and [people said] that's what happens when you don't obey."

No one living, of course, knows of Irene Corbett's last hours. But Don Corbett guesses, based on his grandmother's personality, what might have made her one of only 14 second-class women — of the 97 women on board — to die.

"Her inclination would be to hang back and not get in the first lifeboats," he says. "Because of her instincts as a nurse and her nature and her desire to help others. Maybe she waited too long before she tried to get into a lifeboat," he says.

Irene's father, Levi Colvin, anxiously wired New York for more information. The Saturday, April 20, 1912, Salt Lake Tribune reported that in reply he got a telegram from the White Star Line, owners of the Titanic: "New York, April 19, Levi Colvin, Provo, Utah. ... find name of Mrs Irene C. Corbett is on the list of passengers having sailed from Southampton, but regret is not a survivor on Carpathia."

One of the ships that responded to the Titanic's frantic distress calls was the Virginian. The ship, in which Irene Corbett had so little trust, set course for the sinking Titanic, only turning away when the RMS Carpathia, a transatlantic passenger steamship, signaled that it was less than 60 miles from the Titanic.

Don Corbett feels a close kinship with his grandmother. He, like her, felt drawn to reach out to help people. Corbett, 75, is retired from a career as a family and marriage counselor. In 1997, he and his wife returned by ship from a trip to England. "We went right over the site of the sinking."

"Grandma Irene has been an influence on me, even though I've never met her," he says of his legendary ancestor. "I would love to talk to her someday, if I can."

facebook.com/nowsaltlake

Twitter: @gwarchol —

A look back: Titanic anniversary

See historic photos of the Titanic.