This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Moab • Ensconced at the base of the La Sal Mountains, 15 miles south of Utah's redrock capital, storied environmentalist Ken Sleight looks out over the landscape of a rich life.

Immortalized as Seldom Seen Smith by Edward Abbey in his 1975 anarchist primer "The Monkey Wrench Gang," Sleight, now 87, ponders the past and future of his beloved Colorado Plateau.

He moves a little slower these days and has just undergone surgery to remove cancerous skin cells from his nose. But Sleight's insights are as sharp as ever. Glen Canyon, Bears Ears, wilderness designations, tourism and voting rights for American Indians continue to occupy his mind, as they do for Jane Sleight, 73, his wife of 32 years.

In their small house tucked back on Pack Creek Ranch along Desert Solitaire Road, the couple are working toward a Glen Canyon installation at the John Wesley Powell River History Museum in Green River. The wonders of the now-submerged canyon still haunt Ken as he recalls his early days as a river guide in the 1950s, '60s and '70s.

"It was Glen Canyon that changed my whole life," he says. "It made an environmentalist out of me."

Fact and fiction • During the mid-1950s, after a stint for Uncle Sam in the Korean War, Ken set up a guide service on the Colorado River out of Moab. He was a natural outdoorsman, but the damming of Glen Canyon in the early 1960s — giving rise to present-day Lake Powell — radicalized the soft-spoken Cache County native into a fierce protector of southern Utah's redrock wilds.

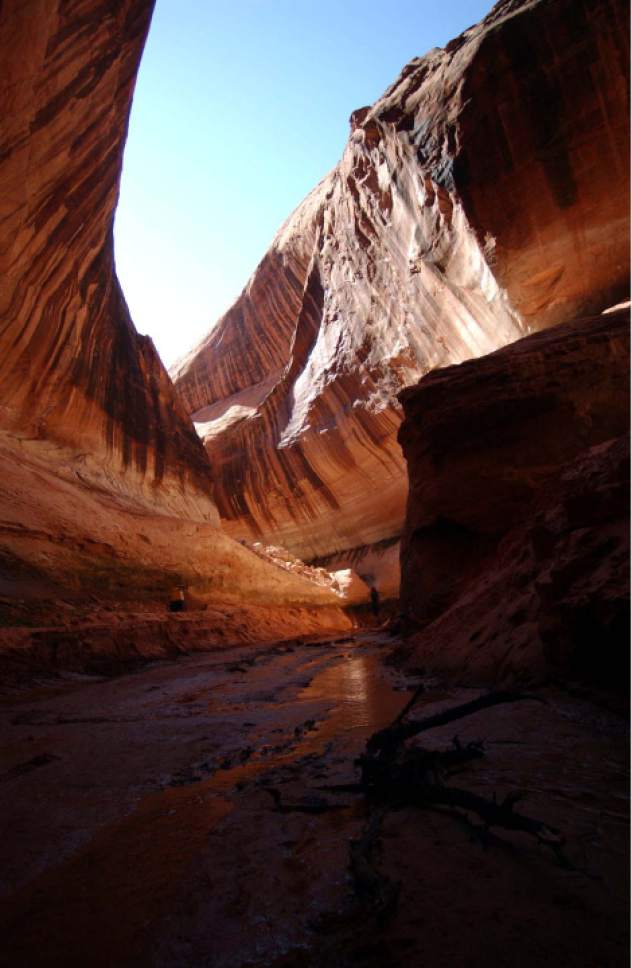

Sleight took to ferrying people up and down Glen Canyon, attempting to show its spectacular wonders to as many people as possible before it was buried. When the water came up in 1963, gems such as Cathedral in the Desert, Moqui Canyon, Music Temple and Forgotten Canyon were drowned.

In "The Monkey Wrench Gang," Abbey draws Seldom Seen Smith as a "Jack Mormon" river guide who talks a lot like Sleight. He is one of four main characters, along with Doc Sarvis, Bonnie Abbzug and George Hayduke. Together, they work to thwart interests that would pollute or despoil the Colorado Plateau and its waterways — but most of their revenge is focused on Glen Canyon Dam.

In real life, Ken and the Western River Guides Association, which he had founded, were too small and unorganized to stop the dam. David Brower and his Sierra Club, on the other hand, turned their backs on the effort to save Glen Canyon — a decision Brower lived to regret.

In summer 2000, Ken joined forces with Jim Stiles, the feisty editor-publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr, to establish a southeast Utah chapter of the Sierra Club. Their little-disguised mission: to drain Lake Powell. But the statewide chapter, based in Salt Lake City, opposed the notion, fearing the Sierra Club would be cast as environmental crazies.

Now, Jane and Ken are searching for artifacts, such as old river boats, that may be in the hands of various collectors, along with historic photos and other keepsakes, in an effort to ensure the canyon's treasures are not forgotten.

"I've given up hope that Glen Canyon will be restored in my lifetime," Ken says. "But this [museum] is the next best thing."

Paradise lost • Grand County's sandstone landscape is not nearly the lonely place it was 50 years ago, when Abbey penned "Desert Solitaire."

Ken confesses, somewhat sheepishly, that he promoted tourism in the area decades ago out of necessity.

"It was great when we first came down here," Ken says. "But we had to get out and really push for people to come and employ our services."

As a stopgap, he and Abbey bought a melon farm in Green River. It was less than a great success — they just weren't cut out to be farmers.

But Abbey's warnings about "industrial tourism" came to pass in and around Moab, Jane laments.

In the '80s, she tried to persuade the Grand County Commission to pump the brakes on its promotion of Dead Horse Point, Arches and Canyonlands.

"I told them, 'This is the most special place I've ever lived. ... What this country has is solitude,' " Jane says. "They laughed at me. Now it's bumper to bumper."

Ken fears the same fate awaits San Juan County with then-President Barack Obama's designation of Bears Ears National Monument. The retired river guide had spent decades fighting to get a wilderness designation — forbidding vehicles of all types — for the spectacular and varied landscape that sweeps across 1.3 million acres.

"When [the tribes] first started pushing for the monument [seven years ago], I figured they had given up on wilderness designation," he says. "I'm afraid it's going to end up like Arches and Canyonlands [national parks]. What are we going to do with the hordes of people? That's what I'm afraid of."

It leaves him in a bit of a quandary because Ken always has supported American Indian self-determination. Not only did the Navajos and four other tribes push for the monument, they are dead set against scaling it back, as President Donald Trump's Interior secretary, Ryan Zinke, has proposed.

A stalwart preservationist, Ken was among the founders of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance. He also helped halt the construction of a proposed Book Cliffs highway between Cisco, 30 miles east of Green River, and Myton, outside Vernal. That battle, by the way, isn't over as various forces persist in pushing for the road.

By the mid-1980s, Sleight had sold his river-running operation to his eldest son. That's when Jane, who had relocated from Jackson Hole, Wyo., to Moab, met up with the redrock activist. When the couple decided to marry, Jane realized that something had to change.

"It was clear we weren't going to make any money with trail rides in Arches," she says. "Ken's expertise was in outfitting, so it had to be that."

As it turned out, Pack Creek Ranch — 10 cabins, a lodge, a barn and a corral — had just come on the market and Jane determined to work some magic to secure their future. In 1986, somewhat miraculously, she put together financing to buy the 300-acre ranch for dudes who didn't require much pampering.

The place was a hit and became a bit of lore itself, with streets named Abbey Road and Seldom Seen Road and, of course, the living legend himself, who led packhorse trips and was always available to sip coffee and chew over the geography of the region.

Playing politics • About that time, Ken threw himself into San Juan County politics. Mark Maryboy had become the first Navajo elected to the County Commission in 1986. Sleight and a group of Democrats launched a drive in 1990 to register American Indians in an effort to run a slate of candidates against the white Republican power structure. The campaign was dubbed "Niha-Whol-Zhiizh," which means, "It's our turn."

Sleight headed the ticket as a challenger for a seat in the Utah Legislature. "It was pretty close," he recalls. "But we lost."

Even so, Sleight feels good about revitalizing the Democratic Party in San Juan County. "Up till that time, there were almost no Navajos registered," he says.

But all these years later, Ken still worries that Navajos go underrepresented.

In 2016, the American Civil Liberties Union filed suit against San Juan County on behalf of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission alleging violations of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the 14th Amendment.

The action came in response to the county's decision in 2014 to switch to mail-only balloting, leaving out many Navajos. Since then, county officials have determined to open three polling places.

"There is a fear among whites that they don't want to turn the government over to Native Americans," Ken says. "It's time we have more involvement from the Indian people."

It's been about 10 years since Ken and Jane sold off the cabins to individual owners, as well as the acreage, barn and corral. But they're still at Pack Creek among the trees and redrock.

"I can't imagine living in a more beautiful place," Jane says.

It's a landscape that continues to hold them tight — body and soul.