This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The Grand Canyon will get more seasonal floods to churn up sediment and build Colorado River beaches and sandbars under a Glen Canyon Dam flow protocol announced Wednesday by U.S. Interior Secretary Ken Salazar.

The move amounts to a small victory for environmentalists, fish biologists and park managers who want to restore some of the natural processes that the dam blocked. But it could cost regional electric ratepayers millions.

Salazar will order the government to routinely crank up flows whenever spring or fall rains create conditions likely to maximize sediment flows.

"We're protecting one of America's iconic natural treasures," Salazar said.

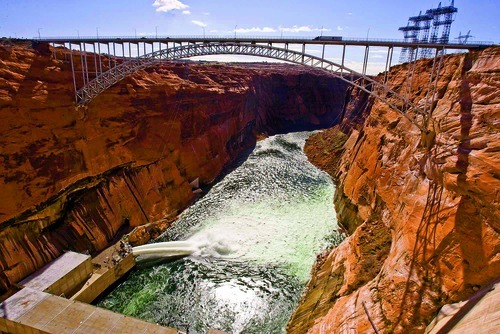

The dam's 1963 construction near the Utah-Arizona border choked off most of the sand and mud that the Colorado River once pumped downstream to form sandbars and beaches that aided both endangered fish and river runners' camping. The new plan will blast 31,500 to 45,000 cubic feet per second from the dam for up to 96 hours to wash sediment downstream whenever monitoring indicates there's enough material entering from the free-flowing Paria River on the Utah side and the Little Colorado on the Arizona side.

Salazar's order will allow flood releases on short notice, unlike previous tests that required extensive study and preparation, and will last through 2020. The Bureau of Reclamation and National Park Service are conducting an environmental study this year to create a long-term management plan for the dam.

The Grand Canyon Trust, which sued in 2007 and remains in court seeking flows to save the endangered humpback chub, celebrated the announcement.

"It's good news for the canyon and people who care about the resources, because most of the resources depend on sediment," trust Program Director Nikolai Lash said. "[The Grand Canyon] is starving for sediment."

The program will not increase annual flows out of Lake Powell, Salazar said, but could have minor effects on hydropower production as release times change. He is ordering the department's agencies to collaborate to ensure the dam still provides water for 25 million people, irrigation for 2.5 million acres, electricity to 6 million people, water and cultural values for American Indian tribes and a recreation industry registering in the billions of dollars.

The dam powers more than 1.5 million homes, including mostly rural and suburban Utahns. They share the costs of water bypassing Glen Canyon's turbines for the flushes, which in the past have cost $3 million to $4 million. In northern Utah, Murray, Bountiful and Tooele are among the hydropower users.

"It's basically wasted water," said Leslie James, executive director of the Colorado River Energy Distributors Association. The high flows, bumped up from releases that fluctuate above minimums of 8,000 cubic feet per second, also complicate legal requirements to deliver water quotas from the upper Colorado River states to the lower.

"You're obviously pulling it out of some month or other," she said, and it could create trouble if it means releases must be curtailed in peak-demand months of summer and winter.

Still, James said, she's "cautious" instead of opposed and will wait to see how technical advisers plan the releases. She is most skeptical of the prospect for spring flushes — something that a previous decision said won't happen for at least two years — because spring tests seem to benefit nonnative trout that eat the native fish.

Salazar's order follows three high-flow tests conducted in 1996, 2004 and 2008. Researchers then determined these "grand flushes" helped build beaches and protect fish such as the humpback chub but that the benefits soon subsided as the new beaches and bars eroded. Researchers found that the 1996 test may have done more harm than good because there was insufficient sediment to push around — just a gush of cold reservoir water that's disorienting to native canyon fish.

The idea now is to boost flows more regularly — as often as once every March-April and October-November if the weather cooperates — to more closely mimic nature. But, in many years, conditions don't exist that would warrant the floods.

"You need monsoonal activity or big snowmelt," Lash said, "which we didn't get this year."

But Salazar said it's possible river managers could flood the canyon this fall.

The department also will try to remove some of the trout from below the dam to reduce predation on endangered fish. Because some tribes consider it a sacred location of their creation legends, the government will attempt to live-trap and relocate the fish.

"The taking of life in the Grand Canyon is offensive to some of the Native American tribes," said Anne Castle, assistant Interior secretary for water and science.

Lash said an all-time high of a million trout now swim the canyon — aided, in his view, by fluctuating daily flows triggered by peak power needs — and he hopes the longer-term plan will adopt year-round flows that favor native fish.

Twitter: @brandonloomis