This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Moths, like many insects, are governed by smells that tell them where to find food, where to lay eggs and, of course, with whom to mate.

New research by University of Utah biologists illuminates how pheromones released by female moths to advertise their sexual availability kick-start males into flight. The olfactory experience prompts the males to quickly warm up their flight muscles and take off in search of a good time — and a chance to contribute their genomes to the next generation.

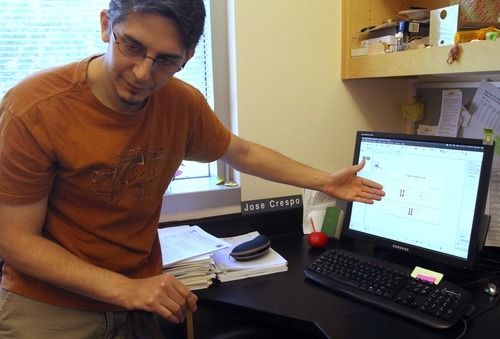

But researchers were surprised to find the stimulated moths are taking flight long before their thoraxes are warm enough for optimal flight, according to Jose Crespo, a doctoral candidate who conducted the experiments.

That points to an intriguing evolutionary trade-off. Is it better for the male to depart earlier or wait and fly better? Since Crespo was looking only at take-offs, answering that question will have to wait for future research.

"The important thing is decision making. This has to do with sensing stimuli that can be visual or olfactory, and responding appropriately. It tells us how animals make decisions," Crespo said.

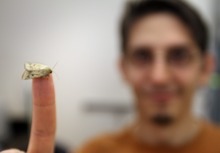

Crespo's team used the moth Helicoverpa zea, a member of the vast noctuid family whose species number more than 35,000. Scientists work with this species because it's a serious agricultural pest and is a good model for understanding how insect brains process odors.

H. zea is commonly known as corn ear worm, but the name changes depending on the crop that is being destroyed. Crespo's findings could help develop non-toxic methods for disrupting the moth's reproductive behavior, thereby controlling their numbers without pesticides.

Each moth species releases a unique blend of up to five pheromone compounds to bring males and females together for mating.

"You can imagine with 35,000 species there is a lot of cross talk out there. They are all using similar words, if you will, but arranged in different orders," said Neil Vickers, senior author on the study and the chairman of the U. biology department. Males have to be picky when interpreting these pheromonal sentences.

"Otherwise you can make a mistake and that can be very costly. If they end up coupling with the wrong species, they become tangled and can't decouple," he said.

Not only do males have to hook up with the right female, they need to get to her fast if they are to leave a genetic legacy. Natural selection favors those who arrive early in "the scramble competition" among males seeking mates.

Crespo built a foot-long wind tunnel for his experiments. He placed one of six scents at the upwind side of the cardboard box, propelled by a 1 mph breeze toward a virgin male. One of the scents used was H. zea's regular sex attractant. He observed and timed pre-flight behavior in which males contract their opposing flight muscles at the same time, making them "shiver" and warm up. Using infrared cameras, he monitored changes in their temperatures.

In the study's second phase, he recorded moths' lifting force at varying thorax temperatures. He had them grab onto a small Styrofoam ball and tethered them to a force meter. When he pulled the ball down, they instinctively took off, pulling against the meter. He discovered that optimal take-off occurred at a thorax temperature of 90 degrees. In the pheromone test, they took off, on average, at 82 degrees after exposure to the sex attractant.

"Insect flight muscles are among the most metabolically costly in the animal kingdom. In order to fly, you have to use a lot of oxygen and generate the power," Vickers said. "The decision to take flight after a female odor is not one that would be taken lightly by the moth because it's expensive."

The study, supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, appeared online Thursday in the Journal of Experimental Biology. U. biologist Franz Goller is a co-author.