This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Provo • From his seat in the old Cougar Stadium on a November afternoon in 1972, Gary Sheide watched as BYU continually called running plays, barely believing he was about to become part of a revolutionary offense.

Coach LaVell Edwards kept telling Sheide during the junior college quarterback's recruiting visit that BYU soon would throw the football, because an old-style approach was historically unsuccessful. Deciding to "trust what he says," Sheide came to BYU and helped launch an offense that would not only transform the program, but also change the game elsewhere.

As the 40th season of the BYU passing offense begins next month, the Cougars' opponent will be Washington State, coached by Mike Leach. College football's most celebrated practitioner of the passing game traces his scheme directly to BYU, where he was a student in the early 1980s and later returned to study the offense.

BYU's impact is "indisputable," Leach said. "It had a lot of influence on me."

And it all started, basically, out of desperation.

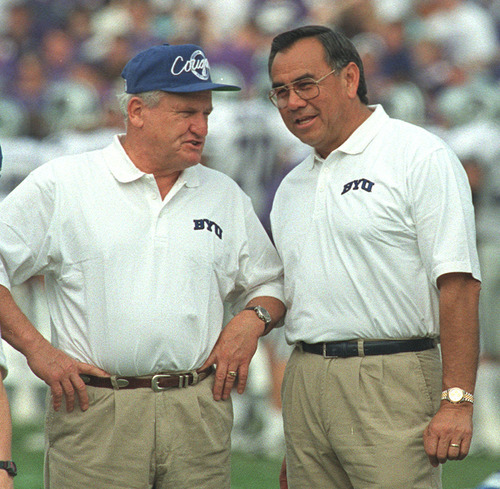

Before taking over in '72, Edwards was an assistant coach for Cougar teams that posted a 45-56 record in 10 seasons. "So I figured I might as well try something different," Edwards said.

Out of that practical, yet daring decision came an offense that forever altered BYU football, with All-America quarterbacks, a Heisman Trophy, a national championship, an expanded stadium and a style of play that helped BYU develop its own brand.

The irony is that in Edwards' first season, Pete Van Valkenburg led the country with 1,386 rushing yards as BYU went 7-4. Yet Edwards was committed to passing as a long-term approach.

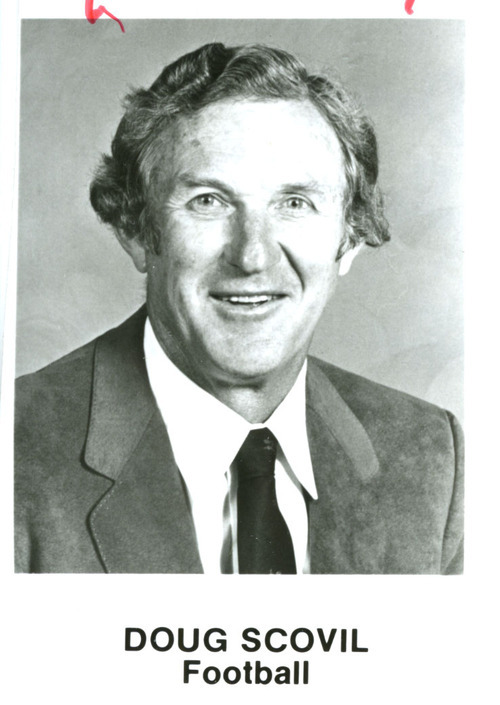

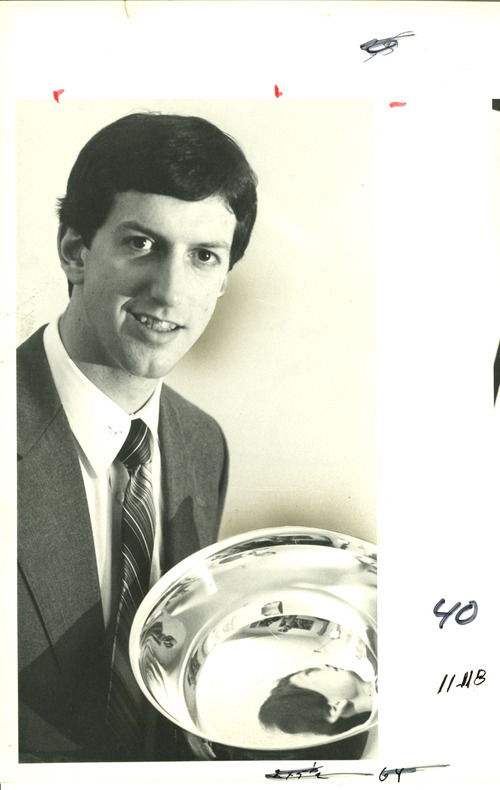

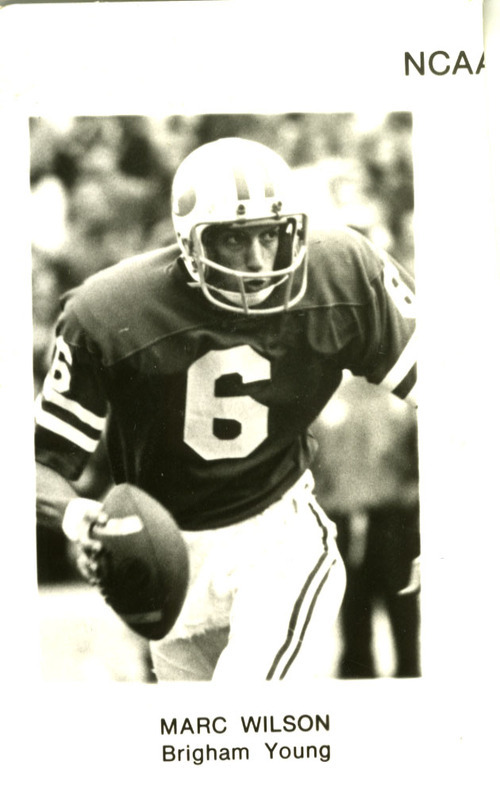

Sheide's two-year career under quarterback coaches Dewey Warren and Dwain Painter ended with a Western Athletic Conference championship and Fiesta Bowl appearance in '74. The evolution accelerated in '76 when Doug Scovil arrived from the San Francisco 49ers as offensive coordinator. Scovil and Bill Walsh, who was developing his West Coast offense in Cincinnati in those days, never worked together, but they were friends. So while their schemes were not copies, there were obvious similarities.

Scovil, who died in 1989, had coached future NFL quarterbacks Roger Staubach and Bob Lee in college, then worked for the 49ers while dreaming of a system he would implement if he ever got the chance. Edwards gave him that opportunity — and Walsh encouraged Scovil to take it, according to Edwards.

Scovil's offense, as initially operated by quarterback Gifford Nielsen, featured Walsh's basic principles: a ball-control passing game, stretching the field vertically and horizontally and throwing to the running backs.

"It's not the complexity, but the simplicity," said Mike Sheppard, a longtime NFL coach who was a graduate assistant under Scovil. "After all this time, that becomes the thing you marvel at."

The passing game became an equalizer for BYU, making up for personnel deficiencies. Yet "even when we started to get good players," Edwards said, "we stayed with it."

Todd Christensen, who would become an All-Pro tight end, caught 101 passes in two seasons as a fullback in Scovil's BYU scheme. "He saw the entire field," Christensen said. "He made sure people in the secondary were busy."

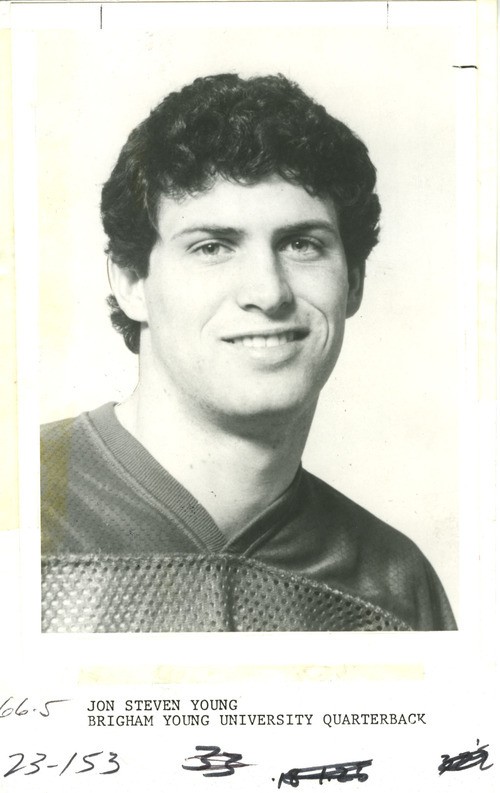

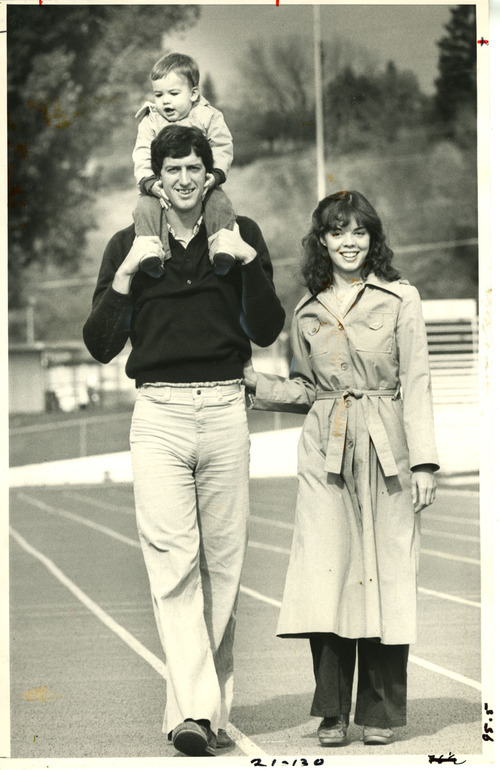

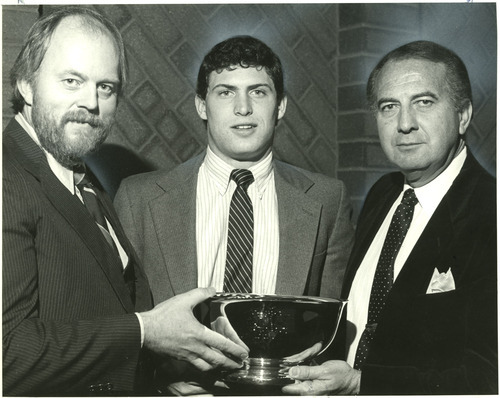

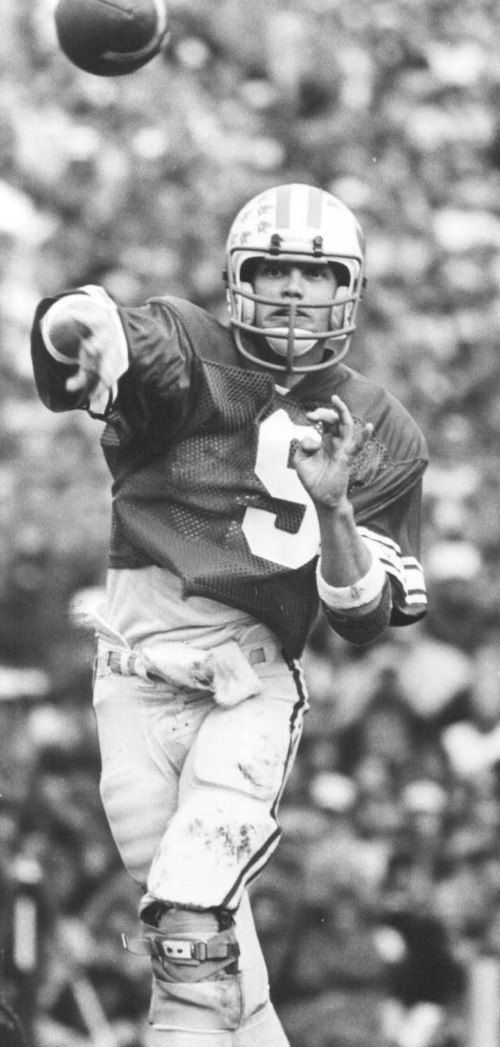

Defenders were preoccupied, and they were confused. "BYU won in the late '70s and early '80s because nobody could figure out what was going on," said quarterback Steve Young. "The ball was out, people were running around, you couldn't cover anybody. We were the beginning of a movement that was ahead of the game, and it was so much fun. Every year, you'd get these intense situations where the defense would start yelling at each other. And then I'd play with the 49ers, and it was the same thing."

A member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Young is amazed to think how as a wishbone quarterback in high school in Connecticut, he went on to play for legendary passing innovators: Edwards, Sid Gillman with the Los Angeles Express of the USFL and Walsh with the 49ers.

"They're all connected," Young said, "and they all were way ahead of their time."

After Scovil became San Diego State's head coach in 1981, quarterback coaches Ted Tollner, Mike Holmgren and Norm Chow succeeded him at BYU. Gary Crowton installed his own version of the offense when he replaced Edwards in 2001. Bronco Mendenhall succeeded Crowton in 2005 and hired Robert Anae from Leach's Texas Tech staff as offensive coordinator, then promoted Brandon Doman in 2011.

This season, Riley Nelson will quarterback "the BYU offense," said Doman, referencing the traditional approach. Nelson observed that other programs' signature schemes, such as Texas' wishbone offense, have gone away, but "ours was so cutting-edge that here we are 40 years later, still running it."

Or, more accurately, throwing it. —

The BYU offense explained

BYU's passing offense is designed to stretch the field vertically and horizontally, using all five eligible receivers. It involves clear-our routes to create seams in the middle of the field for the tight end and flare patterns to the running backs. On each play, the quarterback goes from one potential receiver to another, based on timing, and taking what the defenses gives. "If you go through your progressions and are patient," quarterback Riley Nelson said, "there's always somebody open."