This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

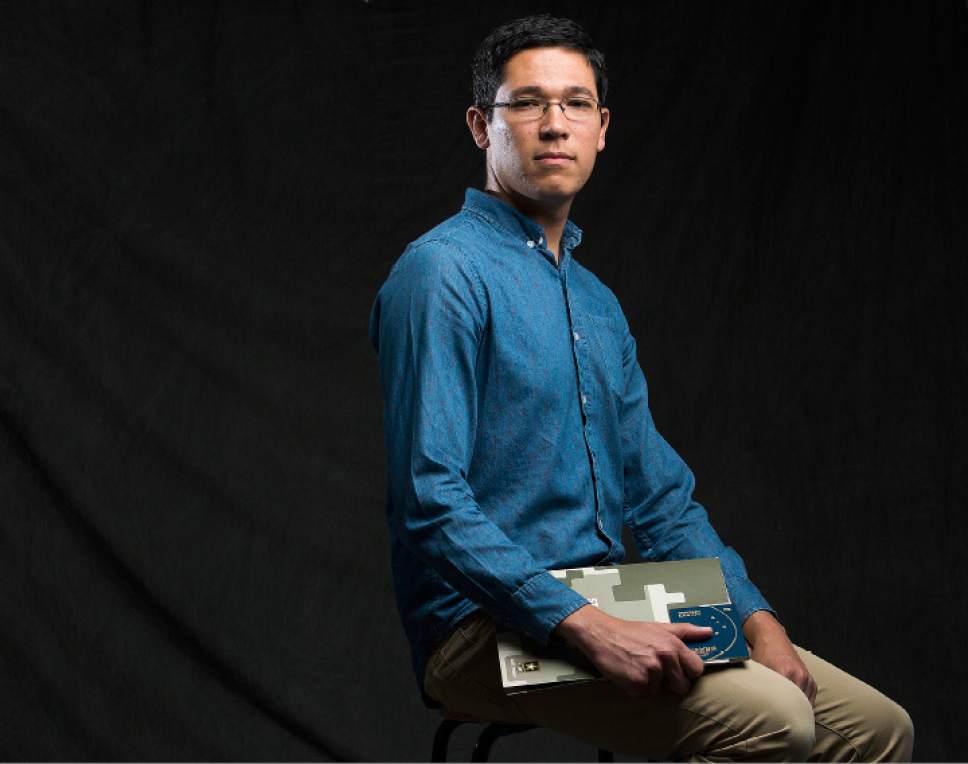

Jullian Anderson Fernandes de Melo faces a stark set of options: He could either become the latest foreign-born Utahn to serve in the Army, as he desires, or he could be forced to leave the country.

The 28-year-old Brazilian national has a skill — fluency in Portuguese — the military needs. But his enlistment in a program that provides a path to citizenship for immigrants came at a time of heightened scrutiny of foreigners that now leaves him facing an uncertain future with the military and therefore the country.

"I am not illegal," said de Melo, who came to Utah in 2013 on a student visa. "But I do not have a status. It's a legal limbo."

He is one of thousands of foreign-born U.S. residents the Army sought to enlist for their medical knowledge or foreign language skills who now are awaiting news from the Trump administration. The program has faced delays that started while President Barack Obama was still in office.

The Department of Defense is now weighing what to do with the program and contracts that affect thousands of foreign-born U.S. residents who sought to gain citizenship through military service.

The Washington Post first reported an unclassified document sent in May to Secretary of Defense James Mattis that showed the military is considering ending the program and tearing up contracts with enlistees. The Salt Lake Tribune obtained a nonredacted copy of the memo Tuesday.

"Execution of the ... enhanced screening process has diverted already constrained Army [counterintelligence] fiscal and manpower resources from their primary roles in support of the global Army [counterintelligence and security] mission," the May 19 memo states. The document was written by Tony M. Kurta, who is Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and Todd R. Lowery, Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence.

The two officials said the program, known as Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest (MAVNI), had presented a "significantly elevated risk" to the Department of Defense.

"Accordingly, we intend to discontinue the MAVNI Pilot Program," they wrote.

That's what leaves de Melo in limbo.

To enlist in the Army, de Melo said he was instructed to authorize his early withdrawal from the student visa program before he graduated from the University of Utah.

The move was supposed to set him on a pathway to citizenship after completing basic training, a process he said has been pushed back multiple times since he signed an Army contract Feb. 25, 2016.

"I would never imagine that it would take me down this route to lose my status and be kind of grasping at straws here and try to find a way to stay in the country legally," he said.

The Utahn's story mirrors others in the state and across the country who are awaiting news of their future in the country.

Margaret Stock, an Alaska-based attorney, was the original project officer of the MAVNI program. She said it filled a need created by a drop in U.S. immigrants who join the military, which she attributed to a "broken" immigration system.

MAVNI recruits had already been subject to heavier scrutiny than others who join the military.

"They're already legal immigrants [who] passed all types of checks before walking into a recruiting station," Stock said. "They already have more checks than any other recruit that walks into a station."

Stock said the delays started last year when the Department of Defense determined the recruits should be subject to higher security checks.

"They've had some screenings, but they haven't had the single scope background investigations," Stock said. "They only do that on people who need top secret clearance."

The memo, and stories from dozens of MAVNI recruits who actively seek answers on social media, indicate the Trump administration is now considering its options for the stalled program as the agency considers what to do with four identified groups of recruits.

De Melo is in what is known as the Army's Delayed Entry Program, a group of about 1,800 that Department of Defense officials deem the lowest risk among MAVNI recruits "but higher than the non-MAVNI Service member population."

The memo says it is "infeasible to continue to process" recruits in the Delayed Entry Program (DEP) because the department's resources are going to vet recruits it considers higher risks. DEP recruits like de Melo present the least risk, the memo says. "Little to no access to military personnel, facilities, equipment, or information."

The memo included action items for each of the four groups. For DEP recruits: "After the development of a Legislative Affairs/Public Affairs strategy, cancel all DEP enlistment contracts," Kurta and Lowery write in the memo.

Action items for the other groups include leaving it to Mattis to determine who will continue in the program and who will be dismissed from the military.

That leaves de Melo to wonder and ponder the future.

"There is the concern always in the back of your mind: what if [my enlistment] for any reason is not approved, what then?" de Melo said. "[I] Hope that whoever is making those decisions that they will be sensitive and be thorough enough to understand that we have been put in this legal limbo by no choice of our own."

About 10 percent of the group no longer have valid immigration status, the memo notes. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services has deferred deportation due to their status with the military.