This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In 1915, Salt Lake City detectives tried to find out who murdered Olivia Cooper by resorting to the most advanced scientific method then available — photographing her eyes.

It was believed that Cooper, who suffered a fractured skull during the midnight robbery of a downtown confectionery, had gotten a good look at her killer.

We're talking cutting-edge technology, people. Detectives had learned that taking pictures of human retinas reportedly had been done successfully (not) in Europe.

The police had two major problems. First, it was a good 50 years before scientists would prove conclusively that the human eye doesn't have an automatic "save as" feature. Second, just because something sounds wow-smart in a newspaper (or on the internet) doesn't guarantee that it actually is.

Anyway, all Salt Lake City detectives got for their troubles in 1915 were some highly magnified and expertly lighted pictures of a pair of dead eyeballs. The case never was solved.

Forensically, things hadn't changed much by the time I became a cop in the late 1970s. I once guarded a huge hole in the ground for 36 hours until Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms agents and techs arrived, took one look, and told me what I already knew.

Them • "Looks like someone set off a bunch of dynamite, Officer Kirby."

Me • "Yeah, I'm kinda wishing I had some right now."

I'm happy to report that forensic science has grown up a lot since then. I thought I knew just how much because I watch cold-case-file television programs in which brilliant and attractive CSI techs solve a series of vicious murders by carbon dating a month-old rat fart.

Curious, I visited Utah's new crime lab Thursday. Director Jay Henry gave me a tour. First, though, I had an important scientific question I wanted answered.

Him • "No, we can't print out images from the eyeballs of dead people."

Me • "Still, huh?"

There are machines at the lab for analyzing virtually everything else, though — body fluids, hair, bullets, handwriting, shell casings, tool marks, fingerprints, explosives, UFO parts, even Bigfoot droppings.

I made up a couple … OK, one of those. But the lab does have microscopes powerful enough to locate and measure the brains of politicians.

There's a catch. Crime labs — up to date ones, at least — are expensive. We have to decide how much we're willing to pay for proof that can bring justice.

The recent controversy over the number of untested rape kits prompted the state to get off its wallet and start funding the science aspect of crime solving.

The beauty of science is that it doesn't have an agenda or a predisposition. It also can "un-solve" crimes, meaning that it has the power to set free the wrongly convicted.

For me, that's the cool part. Human opinion is both a poor arbiter of truth and a great provocateur of stupidity.

A year after Salt Lake City detectives failed to get the image of a killer from the eyes of a dead woman, people in Tennessee hanged a circus elephant for squashing a handler. I am not making this up. Check it out.

I came away from the crime lab tour feeling both relieved and disconcerted. I want justice to be based as much as possible on fact.

At the same time, I realize that if all of that science had been available to authorities by the time I was 6 years old, my life today would be very different.

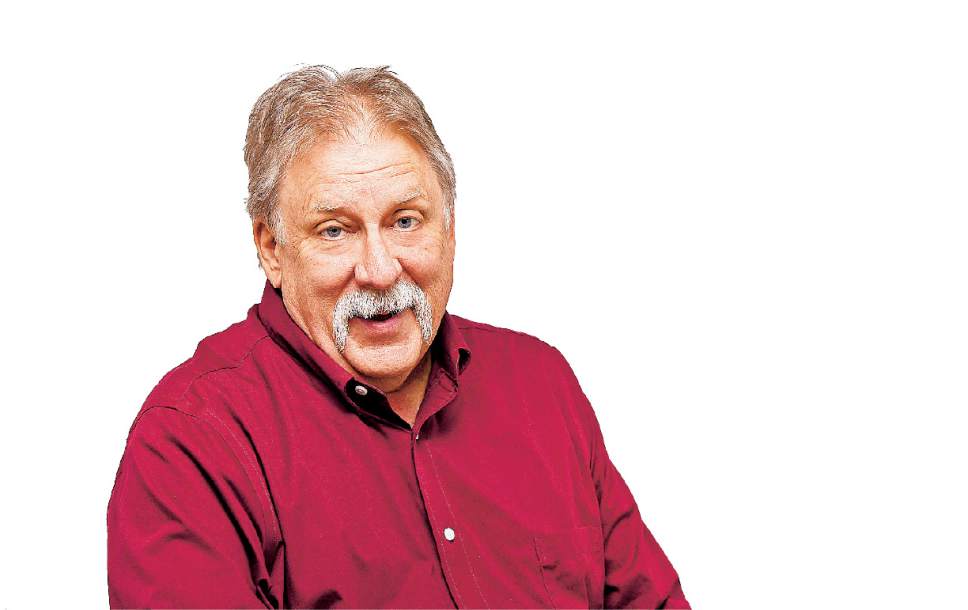

Robert Kirby can be reached at rkirby@sltrib.com or facebook.com/stillnotpatbagley.