This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Delta • For Bobby, Daniel and Carol Hirano, the hot, bouncy bus ride through Delta's agricultural sprawl to the Topaz camp was a bit of a homecoming. As the school bus circled what remains of the mile-square internment camp, three generations of the Bay Area family peered out the window envisioning what this place was like for parents James and Mary, who were sent here with two of their children.

Between 1942 and 1945, they resided in Block 11-C.

Daniel and Carol were born in the block's infirmary, which doubled as a laundry, one of the few facilities with running water. On a previous visit, Daniel sought the place out.

"I wanted to stand in the exact spot where I was born," said Daniel, now a 74-year-old resident of Moraga, Calif. "I went to the concrete pad. You could tell where the plumbing was."

The Hiranos were among more than 400 Topaz internees and relatives who traveled to Delta for Saturday's dedication of the new Topaz Museum. A project 30 years in the making, the museum commemorates the injustice endured by 120,000 West Coast Japanese-Americans after they were detained in 10 camps following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.

"We come together today as a community that balances immigration and intersects with kindness, or in this case, a lack of kindness," said Jane Beckwith, a founder of the Topaz Museum project. "When immigrants hit a wall of prejudice, language difficulties and political roadblocks, just imagine that, because that's what happened to Japanese-Americans."

A commission investigating the rationale behind President Franklin Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 concluded prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership were to blame for the mass detentions.

"Those are three weak spots that have not disappeared. They have not been put to rest," said Beckwith, an English teacher who became interested in Topaz after taking students there for a journalism project in 1982.

She has spent the years since documenting the experiences of the internees and establishing the museum.

More than 11,000 lived at the Topaz War Relocation Center, hastily built 14 miles northwest of Delta in Utah's West Desert. At its peak population of 8,000, Topaz was Utah's fifth-largest city.

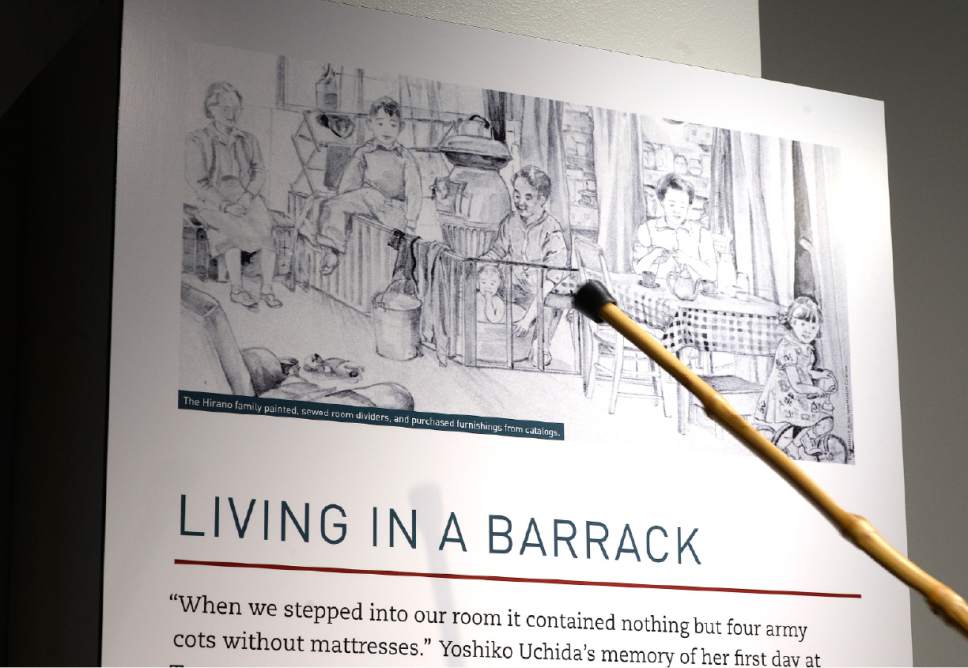

The camp was comprised of 42 blocks, each holding a dozen 120-foot-long barracks and up to 250 people. Today not much remains but concrete foundations. Many barracks now serve as houses in town. A few wound up on the Bunker family's farm. So did blankets and beds, which Gayle Bunker slept in as a child.

"When they closed it down, they had all these things for sale. My folks didn't have a lot of money, so they bought the things out there," said Bunker, now Delta's mayor. "We called them 'Topaz blankets,' but we didn't know anything. It was a time when a lot of people didn't talk about it."

The new museum strives to understand past mistakes so they aren't repeated and bring closure to those whose liberty was taken.

"Let it be remembered that a not single Japanese-American was ever accused, much less convicted, of espionage or sabotage. What was their crime? They happened to look like the enemy," said Oakland attorney Don Tamaki at the dedication program in Delta High School's packed auditorium.

Tamaki served on the pro bono legal team that re-opened the case of Topaz internee Fred Korematsu in 1982. Korematsu had been convicted of resisting incarceration, but new evidence surfaced proving that Japanese-Americans posed no threat to the war effort, ending the claim that mass incarceration was a matter of "military necessity."

Korematsu prevailed on the belated appeal and he now is celebrated as a hero, even in Utah. In 2012, Gov. Gary Herbert proclaimed Jan. 30 Fred Korematsu Day for Civil Liberties and the Constitution.

Although unable to attend the Delta event, Herbert sent his regards through Jill Remington Love, executive director of the Utah Division of Heritage and Arts.

"The internment of Japanese-Americans is a permanent, regrettable mark on our nation's history; but today, we rejoice in the successes and contributions the Japanese-American community has made in Utah," he wrote in a letter Love read. "This museum provides fascinating insight into the diverse voices and talents of the people interned at Topaz."

The letter was followed by Shirley Muramoto's performance of classical Japanese music on a koto, a large, table-mounted stringed instrument. Muramoto's mother learned to play the koto as a girl at the camp, and the musician dedicated the performance to the teacher.

"Everything was by memory; there were no books," Muramoto said. "I'm not sure where she got finger picks. Sometimes they used pieces of wood or cow bones. They made do with what they had."

Music and the arts helped internees endure the tedium of camp life and stay connected with their Japanese heritage.

Yet, they spoke mostly English and enjoyed American pastimes, like sock hops and baseball. And they signed up for war. Some 14,000 young men joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and fought in Europe. Twenty-one from Topaz lost their lives.

"We are going above and beyond to show how American we are," Chris Hirano said during the bus trip between Delta and the camp. His father, Bobby, arrived at the age of 7. Saturday was his first time back. The elder Hirano recalled how he would sneak away to fish and swim in the tanks that held drinking water.

The bus ride followed the same route internees used when transported from the rail depot in Delta to their new home in the desert.

Also on the bus was Rep. Rob Bishop and his family. A onetime history teacher, Bishop said he included a section on Topaz in his Utah history curriculum.

"There are too many lessons to be learned," Bishop mused, gazing out the window at the desolate scene. Among the foundations and debris, little grows other than greasewood and cheatgrass.

"I wish we could spend more to restore some of the barracks to give a sense of what it was like."

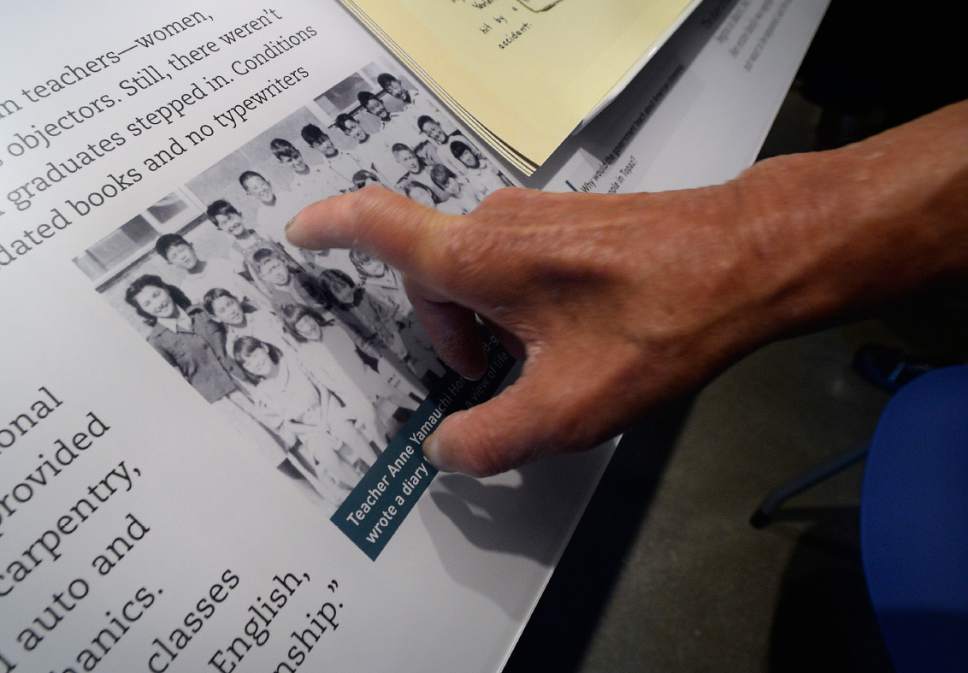

What the camp can no longer convey, however, the new museum brings to life, including a ledger containing all the internees' names and a replica of a barracks room. The exhibit includes a 1943 drawing of the Hirano family, showing father James giving baby Daniel a bath in a tub while Bobby straddles a low partition.

"Can you imagine the snoring in that room?" Chris Hirano exclaimed as the family toured the exhibit. "Snoring runs in our family." Visit the museum

P The Topaz Museum is at 55. W. Main St. in Delta.

For more information, visit http://www.topazmuseum.org/ or call 435-864-2514