This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

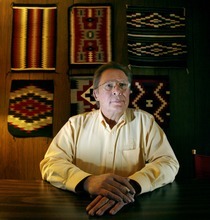

Brian Barnard represented atheists and polygamists, panhandlers and prisoners.

He battled governments — to have a small religious group's "seven aphorisms" placed next to the 10 Commandments in a public park and to remove crosses from public land along the highways. He fought to stop overcrowding in jails and to allow women into private clubs.

On Tuesday, as news of the 67-year-old civil rights attorney's death spread throughout the legal community, Utah attorneys mourned the loss of a "fearless lion" who had an "unwavering commitment to the protection of the people on the fringes of society."

"Brian's death is a huge loss to the community," said the American Civil Liberties Union of Utah in a statement. "Whenever anyone thinks of a civil rights lawyer in Utah, they think of Brian Barnard. He has stood up for the rights of the marginalized and vulnerable for decades and has been instrumental in moving civil rights forward."

The Utah Legal Clinic, where Barnard worked, said he "passed away peacefully in his sleep" in his home near the University of Utah over the weekend. Salt Lake City police said they were alerted to a death at Barnard's home around 11 a.m. on Tuesday. The death was not suspicious, police said, and no autopsy was planned.

For more than 40 years, Barnard was a legal gadfly who once described himself to a Salt Lake Tribune reporter as someone who would never be appointed a judge, invited to join the Alta Club, or called as a Mormon General Authority.

"A skilled attorney, Brian spent his career advocating for those who lacked a choice or the power to do so on their own," the Utah Legal Clinic said in a statement. "Among others, Brian represented homeless panhandlers, women denied access to a myriad of institutions on account of their gender, members of unpopular faiths, prisoners forced to live in deplorable conditions and victims of police brutality. We live in a more just world for his having been with us."

Barnard's advocacy and litigation led to women being allowed membership in the Alta Club in downtown Salt Lake City, as well as the state's Elks Lodges. In 2010, Barnard and attorney John Pace finally settled an 18-year fight between the state and the Navajo tribal members in San Juan County over unpaid oil drilling royalties for $33 million. Even while the case moved ponderously through the courts, Barnard never gave up the fight.

"Our clients were tenacious," Barnard said at the time. "Our cause was just."

Barnard helped end St. George's 40-year practice of covering the cost of lighting the exterior of the LDS temple and brought down memorial crosses for fallen Highway Patrol troopers after arguing that the symbols were not inclusive of all faiths.

"Often times [his cause] was very unpopular," said Kirk Torgensen, an assistant Utah Attorney General. But Barnard filled "that needed role of a voice and an advocate to constantly be on the lookout for government intruding into unconstitutional areas. Brian did that in this state better than anybody."

Barnard grew up in Los Angeles and graduated from Loyola Law School. He came to Utah on a Reginald Heber Smith fellowship, given to young attorneys interested in community-oriented legal work. He worked initially at Utah Legal Services and then started his own practice.

Larry Swanson, Barnard's neighbor, said Barnard won neighborhood respect by fighting for the rights of anyone — even people who "aren't popular, aren't comfortable and…might not be likable." Swanson described Barnard as a gracious neighbor who helped others when needed and was appreciative of the sense of community on their block near the University of Utah.

"We all admired what he did and how he did it," Swanson said.

Stewart Ralphs, executive director of Utah Legal Aid Society of Salt Lake, repeated the comment he made to a colleague when he first heard the news: "It will be a long time before another Brian Barnard comes along in our profession."

Barnard was a "fearless lion" who wasn't afraid to go after any person or institution if he felt injustice was occurring, Ralphs said.

"He was one of those people who practiced pure law," he said. "One may not always have agreed with Brian, but I don't know a lot of people who didn't respect his right to challenge the powers that be or do what his clients wanted."

Ralphs said Barnard used to joke that he loved the period following the end of a legislative session, when he would browse through all the laws that had been passed and see what new work might be in store for him.

"State statutes were one of his favorite targets," Ralphs said.

Assistant Utah Attorney General Thomas Roberts argued opposite Barnard in the highway crosses case, but said Tuesday that Barnard was a good attorney and a fierce advocate.

"He was a great champion of individual and civil liberties in our community," Roberts said. "He's the kind of person and lawyer that every legal community and every civil community ought to have."

Roberts said he saw Barnard on Friday afternoon, when the assistant attorney general handed Barnard a check for legal fees in a case he'd recently won.

Barnard's next-door neighbor of 40 years, Sylvia Mathis, said she will remember the attorney as a friend and fixture in the life of her family.

"He'd been a great neighbor all of those years," Mathis siad. "He always cared for and was concerned about our children —and then, later on, our children's children. He cared about them and they cared about him. It was a sweet side that maybe not everybody would have seen."

Erin Alberty contributed to this story.