This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In a state where Republicans rule the roost, it's hard to imagine a time when Utah's clock turned leftward.

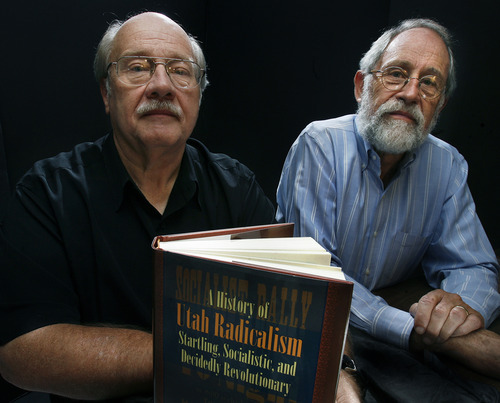

There's no need to imagine it, say historians John McCormick and John Sillito. McCormick is dean of the school of humanities and social sciences at Salt Lake Community College; Sillito is an emeritus professor of libraries at Weber State University. Together, the authors have unearthed a treasure trove of just how red and deep the state's socialist roots once grew. It's all between the covers of their recent book, A History of Utah Radicalism: Startling, Socialist, and Decidedly Revolutionary.

Cedar City twice elected a Socialist mayor. Bingham, Eureka, Murray and Joseph boasted Socialist mayors, too. Some 115 Socialists were elected to office between 1900-1920, including Socialist and active Mormon J. Alex Bevan of Tooele.

Granted, this politically dynamic time didn't last long before The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and the rest of Utah, made its bid for mainstream respectability. But with the backdrop of the LDS Church's decidedly socialistic religious framework, the United Order, it spawned the well-known martyrdom of labor activist Joe Hill, as well as the quirky offshoot of Mormonism known as the Godbeites. Then there's the historical moment when the daughter of an LDS Church president was praised by anarchist Emma Goldman.

McCormick and Sillito's book will receivethe Francis Armstrong Madsen prize for Best History Book at the Utah State History Conference, which runs through Sunday at Fort Douglas. (See box for details).

How did the socialist movement in Utah differ from labor and socialist movements in other states?

Sillito •The radical movement in Utah tended to look a lot like parties and movements in other parts of the country. The majority of party members were LDS, of course, but they kept in touch with other socialist organizers and candidates in the country.

McCormick •Utah socialists wanted to see themselves as part of the larger movement. That meant they wanted to stay in touch. National speakers came through Utah on a regular basis, partly because Utah socialists invited them.

Sillito •It was the crossroads of the West then, even as it's the crossroads of the West now. There's a wonderful story about Eugene Debs [American union leader and a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World] getting stuck out in Tooele after speaking in Salt Lake City. He got stuck in the snowstorm.

McCormick •He wrote a lovely letter to his brother that's recounted in the book: "Whatever possessed you to put Tooelle [sic] into this schedule? … The snow was so deep and the roads so bad that no auto owner would let us have a machine at any price. … In 15 minutes I was half frozen, chilled to the marrow, and my feet soon became like ice. … Must I have such a damned killing dose as (this) administered to me on every trip? I am willing to be killed for the cause but I don't want to die a fool's death."

How much more or less socialist was Utah at the time than the rest of the nation?

Sillito •There were things that happened here that weren't happening in other places. For example, Utah Socialists elected legislators. In other states where Socialists were equally strong, they weren't successful in electing Socialists.

McCormick •State federations of labor in five states officially endorsed the Socialist Party. One of them was Utah. That was a significant sign of their status.

How did Utah Socialists add their own flavor to the movement?

Sillito •Negotiating the dichotomy between short-term goals of improving working conditions on the one hand, and abolishing the system that produced those subpar conditions on the other, was difficult for them.

McCormick •Whenever they gained control they tended to focus on honest, efficient city services. It was important to them that residents had a sewer system, clean water and garbage collection. None of that was radical. It was something everyone could agree on.

But they knew that if they wanted to have a long-term impact, they had to address problems firsthand. They believed that once they solved these problems, they'd gain credibility and trust. Murray City is a great example. One of the main things Socialist Mayor George Huscher did there was establish Murray City Power Department, a city-owned municipal power plant. It's still in operation today. The Socialist administration of Eureka was first to put a sewer system and garbage collection in place.

One of the last stories we heard about Utah's working-class history was in 2000, when the Murray smelting stacks were demolished. A lot of people couldn't understand the symbolic importance of those stacks.

Sillito •When you consciously choose not to preserve sites associated with labor history, some people draw the conclusion there never was a labor history in the state, which just wasn't the case. Some people say it's not conscious. I'm not so sure. I don't know the motives, but I know the result. We're often aghast when there's talk of demolishing a historic mansion, but it's hard to find examples of working-class housing in the state today. Some still exist in west Salt Lake City, Midvale and even Murray. What you preserve, and don't preserve, is often very political.

What are your favorite historical anecdotes from the book?

Sillito •My own favorite stretches from 1905-1918, when the Episcopal dioceses of Salt Lake City was led by Franklin Spencer Spalding, then his successor Paul Jones. Both were Episcopal bishops, both were self-avowed Christian Socialists who believed in replacing "the rule of gold with the golden rule." Neither saw their role as a bishop as promoting socialism, it was just their political viewpoint. When one newspaper reporter asked them about their religious and political affiliations, they said, "Out in Utah there are 700 bishops. Being a bishop is no big deal."

I also have a fondness for Wilford Woodruff Freckleton, who served as a Socialist on the Eureka City Council. He served his [LDS] mission to England, then returned to Eureka to be re-elected, again as a Socialist.

McCormick •What I was always struck by was how pervasive the Socialist influence was. They published newspapers, ran a column in the Sunday Examiner, [a] full page every Sunday for five years. They spoke all over the state, hosting both local and national speakers. They talked about "socialism with sociability." They hosted Socialism Day at Saltair, with Red Sunday celebrations in Liberty Park. They'd invite people together for card games. They'd sometimes dance until midnight. They were concerned with keeping up morale whenever possible to maintain confidence and commitment. In 1915, Socialists in Duchesne sponsored Overnight Encampments in which up to 1,000 people in rural Utah heard theatrical performances and debates.

Opposition brought down on the labor movement is also interesting. In 1913, the Salt Lake City Council passed an ordinance designed to prevent Socialists speaking in public. They wanted Socialists and Wobblies [members of Industrial Workers of the World] to speak only on the corner of Orpheum Ave. and Commercial Street, now called Regent Street. At the time, that was the center of Salt Lake City's red-light district.

If people know any figure from Utah's labor movement, it's Joe Hill. Is his reputation warranted or overrated?

McCormick •It's so complicated. People really need to read William Adler's recent book The Man Who Never Died for the full answer. Hill was an iconic figure whose trial and death in Utah has inspired people everywhere. He had the ability to come up with catchy phrases such as, "Don't mourn, organize," and "Don't listen to people who promise you something in the next life, work for it in this life." Adler shows, I think, that you can make a good case [Hill] was innocent. But why didn't he make a better case himself? Perhaps he thought his death as a martyr was more useful than his life as a worker. I've been studying that case since 1970. I get a new wrinkle on it every time I study it.

Sillito •We need to remember the socialist movement in Utah was not just about men. Kate Hilliard of Ogden was a great suffragist working with Mormon women. Virginia Snow Stephen is very interesting. She was daughter of the fifth LDS Church president, Lorenzo Snow, a friend of Emma Goldman's and an advocate of Joe Hill. She was forced to give up her job as art instructor at the University of Utah in 1916 because of her public support for Hill.

What do you hope people come away with from this book?

McCormick •Though radical movements from the left are often seen as essentially footnotes to the main story of U.S. and Utah history, marginal to the main story and meriting nothing more than passing interest, paying serious attention to them is important. Doing so can illuminate the past in new ways. A different picture can emerge, not only in details, but in essentials, challenging the "master narrative" and requiring us to think differently about the past, and also then, about the present and the future.

Sillito •Every day when I ask my class if they had a great weekend, they say yes. I say, "Good. Thank the labor movement." Utah Phillips [labor activist and songwriter] once said, "The most radical thing is the long memory." In some ways, I think that's true. I hope with this book people understand the past in a different way. If you know the past, you're better equipped to address the future.

Twitter: @Artsalt

Facebook.com/fulton.ben —

The history of Utah's socialist streak

John McCormick and John Sillito, authors of A History of Utah Radicalism, will speak at the 60th-annual Utah State History Conference.

When • Friday, Sept. 21, 10:45 a.m.-noon; conference runs through Sunday, Sept. 23

Where • Officers Club at Fort Douglas, 150 S. Fort Douglas Blvd., University of Utah campus, Salt Lake City

Info • Conference events and sessions are free. Call 801-581-1251 or visit http://www.history.utah.gov for more information.