This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

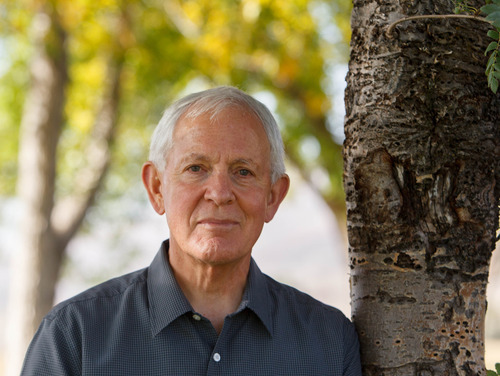

Marlin Jensen was 46, with a 2-week-old baby girl, seven older children, an 800-acre farm in Huntsville and a thriving law career, when, in 1989, he was called into full-time service for the LDS Church.

Jensen knew that being a Seventy for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints would mean constant traveling, public speaking, juggling family with church obligations — and a two-thirds cut in salary.

"I wondered how we would get all the children raised," recalls Jensen's wife, Kathy. "Nobody was married or through school. I was concerned."

But a wise LDS leader reminded her that "we don't know the end from the beginning."

So Jensen, with his wife's support, jumped into the church position with characteristic vigor, good humor and determination.

During the next 23 years, Jensen emerged as a public face of Mormonism to outsiders. He spoke eloquently and personally about his faith and the church's challenges in the 2007 PBS documentary "The Mormons." He urged Utah legislators to be compassionate in their approach to immigration. He became LDS leadership's most visible Democrat and helped heal wounds over the 2008 Proposition 8 ballot fight as well as the 1857 Mountain Meadows Massacre. And, in perhaps his most significant achievement, he oversaw the greatest transformation in the church's historical department since the 1970s and reached out to scholars to make the faith's vast historical holdings widely available.

"He stood up for the things he felt strongly about, and they weren't always popular," says daughter Emily Jensen Snow. "I am proud that he was willing to take on topics that no one else wanted to tackle and say what needed to be said."

On Saturday, during the LDS Church's 182nd Semiannual General Conference, Jensen, having turned 70 in May, will be among those named an emeritus general authority. It will officially end his full-time church service, though he stepped away from his work at the end of August.

He has returned to some work as a lawyer and to his roots in the quiet hills of the Ogden Valley, where it all began.

Learning to labor and love • Jensen developed the qualities that would serve him and his church so well in a childhood spent on a Huntsville dairy farm.

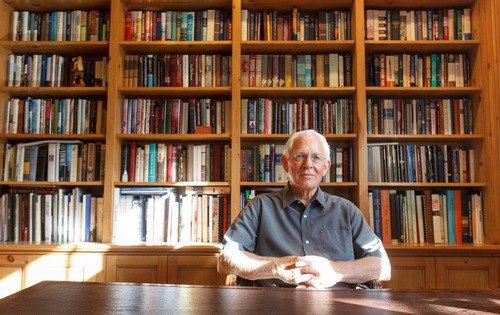

Young Marlin acquired an extraordinary capacity for hard, physical labor. He embraced the values of small-town living, where everyone knows their neighbors and drops everything to pitch in when needed. He inherited his love of reading, writing and Democratic politics from his dad, who served as a Weber County commissioner.

He learned compassion by caring for his older brother, who endured mental challenges, says Kathy Jensen. "That shaped him a lot."

In the early 1960s, a 19-year-old Jensen went to Germany on a Mormon mission. He didn't carry with him the certainty about his faith that seemed to come more easily to other young Latter-day Saints, and he struggled initially with the language.

"Those first few weeks were just absolute misery, because I'm a personable, loquacious person, and I wasn't able to say anything," Jensen explains in the PBS documentary.

After about six weeks, Jensen could offer a prayer in German and a few other simple phrases when he and his missionary partner attended a meeting in their neighborhood. A Lutheran pastor was warning his parishioners about the Mormons and Jensen's 6-foot-7 companion stood to defend their faith.

In that moment, the spiritual conviction Jensen had so earnestly sought came — unexpectedly.

"I remember sort of composing myself and trying to figure out what I might say in German, which is a very logical language if you know the rules," he says. "I remember in that moment about every German word or phrase I had ever read or heard sort of coming together in a way that I was able to express myself."

When Jensen returned to Utah, his faith was secure, but that didn't stop him from a lifetime of thinking, reading and probing.

"If you're honest and if you're really a true seeker ... it tends to bring one to a deeper seeking, and I hope that's what my doubts have done," he says in the film. "They've caused me, I think, to study and to ponder and to compare and, in the long run, to become even more convinced that the way I've chosen, the way that came to me early in Germany, is the right way."

Surrounded by females • Kathy Jensen met her future husband on a blind date. He was attending Brigham Young University, majoring in German; she was at Utah State University, studying education.

The two fell in love and married in 1967. They moved to Salt Lake City for Jensen to go to law school at the University of Utah, while she taught school.

After Jensen earned his law degree — graduating first in his class — the couple returned to Huntsville.

In the next decades, their family would swell to 10, with six daughters and two sons.

"I wasn't sure I wanted to live in a place with only one store," jokes Kathy Jensen, who was from Clearfield, which at least had sidewalks.

Soon enough, though, it became home for the expanding family.

Jensen worked long hours at an Ogden law firm but was no "absentee father," recalls Snow, his fifth child.

He taught his kids how to work — Emily mows lawns better then her husband, she brags — took them on road trips and European adventures, and routinely bought them any book they wanted.

Her doting father "loves the peace and quiet of our mountain home," says Snow, now a mother of four herself, "but he put up with an awful lot of girl drama."

Then Jensen became an LDS general authority and they — especially the youngest, Sarah Jane, who never knew him as anything else — had to share him with a church and millions of members.

On assignment • Jensen first was stationed at the church's Salt Lake City headquarters. To make ends meet, he also did legal work on Mondays, the general authorities' day off.

From 1993 to '95, he served as an LDS mission president in Rochester, N.Y., near the birthplace of Mormonism.

Back in Utah, Jensen joined the church's Special Affairs Committee, which governed public relations. In 1998, then-President Gordon B. Hinckley asked Jensen to talk publicly about being Mormon and a Democrat to help dispel the myth that a faithful member couldn't be both.

He willingly agreed.

"There have been some awfully good men and women who have, I think, been both and are both today," Jensen told The Salt Lake Tribune in a far-ranging interview. "So I think it would be a very healthy thing for the church — particularly the Utah church — if that notion could be obliterated."

A young Ben McAdams, a Mormon who is Democratic state senator now running for Salt Lake County mayor, remembers Jensen's interview vividly. He was interning in Washington, D.C., with the U.'s Hinckley Institute of Politics.

"I was so happy he was willing to stand up for his political beliefs," McAdams explains, "and say it wasn't a conflict."

In fact, it's not a conflict for most of the Jensen clan. Although his wife tilts Republican or independent, all of his kids lean left.

Stephen West, another Mormon Democrat whose service as a Seventy overlapped with Jensen's for six years, also appreciated Jensen going public with his politics.

"It was heartening to me and I think to others," West says. "We didn't talk about politics often — we [Democratic general authorities] are not a very large group — but it's nice to have someone else who feels the same way."

West has "great admiration and respect for Elder Jensen and the dignified way he has quietly held fast to his political beliefs without publicly espousing them," he says. "I think this is a good reminder of the church's attitude against taking political positions as a church and as a church leader but encouraging church members to individually support those candidates and ideas in which they personally believe."

West was also impressed by Jensen's quick smile, cheerful disposition and thoughtfulness.

When West was assigned to give his first talk in General Conference, speaking before millions, the former chief counsel for Marriott Corp. was surprisingly nervous. A few days after his address, West says, he received a note from Jensen praising the talk.

Such kindness, many say, is one characteristic of a man known for his bridge building.

Profound peacemaker • Helen Whitney, the nationally respected filmmaker who produced "The Mormons," met Jensen at a party. She watched as he moved around the room — talking to a young intern, to potential donors, to LDS intellectuals and so on. He wasn't networking, just listening.

"I was struck," she says in a phone interview from New York, "by the depth of his listening to the large and small fish."

When Whitney chatted with him, she was amazed at how jargon-free he was. He could speak non-Mormon. And he was more open than other religious and government officials she had met.

For each film, she says, she was looking for a Virgil, the ancient guide in Dante's Divine Comedy. In Jensen, she had her Mormon Virgil.

"He has a luminous authenticity," she says. "He's funny. He can laugh at himself. He doesn't present himself with that surreal certainty that some Mormons have."

In Whitney's three- to four-hour interview with Jensen, the LDS authority discussed his own faith, his views of difficult historical moments for his church and current controversies.

Whitney was stunned, for instance, when he candidly acknowledged that what Mormonism asks of its gay members — to remain celibate — goes beyond what it expects of others.

"A single woman, a single man who is heterosexual in their thinking always has the hope, always has the expectation that tomorrow they're going to meet someone and fall in love and that it can be sanctioned by the church," Jensen says in the film. "But a gay person who truly is committed to that way of life in his heart and mind doesn't have that hope. And to live life without hope on such a core issue, I think, is a very difficult thing."

It would not be the last time Jensen would express such anguish and empathy.

Healing balm • In 2010, Jensen was the visiting LDS general authority to Mormon congregations in Oakland, Calif., which had been sharply divided over the Utah-based church's support of California's Proposition 8. He agreed to attend a special meeting, where gay members and their loved ones shared their stories of pain. After one particularly harrowing account, many in the room, including Jensen, wept, recounts Mormon author Carol Lynn Pearson.

The speaker said he felt the church owed him an apology.

Jensen arose and, through his tears, assured the group he had heard their pleas and, "to the full extent of my capacity, I say that I am sorry."

Marriage as only between a man and a woman was a "bedrock of our doctrine and would not change," Jensen told the group that day. "However, I want you to know that as a result of being with you this morning, my aversion to homophobia has grown. I know that many very good people have been deeply hurt."

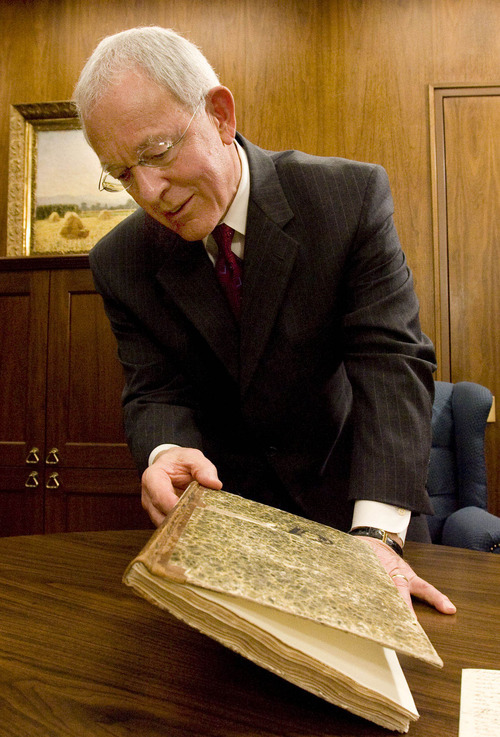

Opening a historical window • In 2005, Jensen got yet another call from Hinckley, who asked the Seventy to become the church historian and recorder.

"What do you want me to do as historian?" an astonished Jensen asked the man considered a "prophet, seer and revelator" by faithful Mormons.

Hinckley replied, according to Jensen, "Read your scriptures and do you duty."

What about the recorder job?

"I haven't given that a bit of thought," Hinckley said. "But you should."

So, once again, Jensen threw himself into the task.

Not trained as a historian, he assembled a team of Mormon scholars and writers as advisers. He was the first LDS general authority to attend the annual Mormon History Association meeting — not to speak, but, in Jensenesque-style, to listen.

"I sensed a man who really was devoted to the enterprise of history," says Ron Walker, one of the professional historians to work with Jensen. "He never attempted to censor, yet he was so willing to be helpful and make resources of the church available. One of his great virtues was the ability to bring out the best in everyone. That's a rare quality."

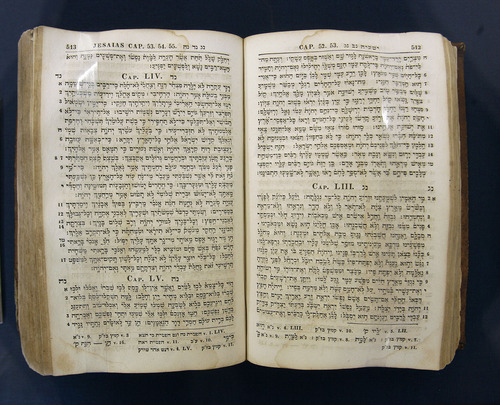

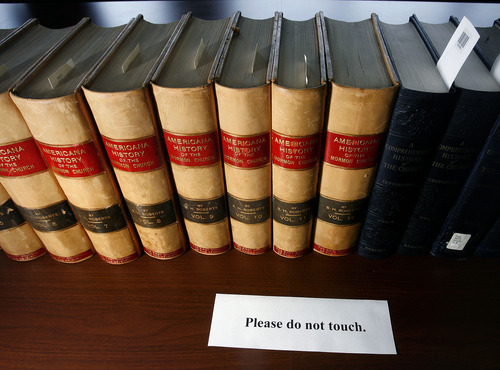

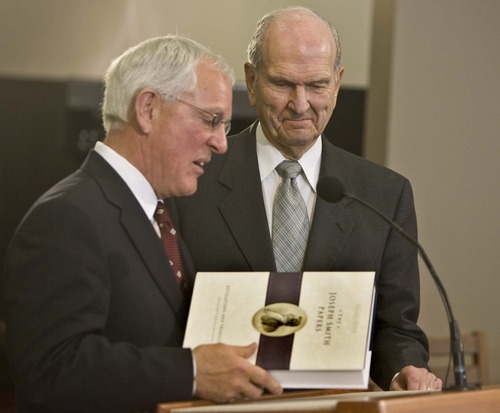

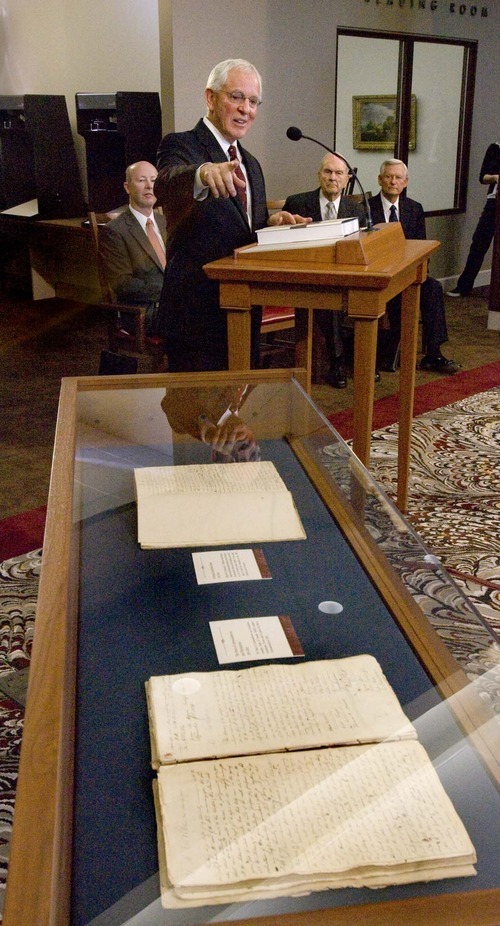

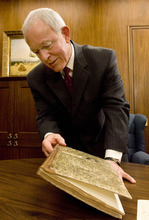

The mild-mannered Jensen helped transform the faith's approach to its history. He put thousands of its documents online, oversaw the groundbreaking, multivolume "Joseph Smith Papers Project," reorganized the staff and moved into a new state-of-the-art building.

"You can be nice and smart and humble and good with public relations, but unless you have a vision before you, it doesn't happen," Walker says. "He had that vision and the people skills to make it work."

Ronald Barney, a longtime staffer in the LDS Historical Department, points out the importance of Jensen's temperament.

"He was always in great humor, incredibly patient and disarmed every difficult administrative situation by his retreat from having to have the last word," Barney says. "He really was a listener, and I don't know anyone who was quicker to laugh. He had no peer in that regard."

Barney, who retired last year, also notes Jensen's "singular skills" at reconciliation.

"I know of numerous times that he quietly met with folks who were outside the circle of orthodoxy or who had been estranged from the LDS Church," Barney writes in an email. "He was always a voice of understanding and grace."

Those skills were on display in Jensen's work with Mountain Meadows Massacre descendant groups.

In the spring of 2008, Jensen traveled to Arkansas to meet with Harley and Diann Fancher, who together had many ancestors killed on Sept. 11, 1857, when a Mormon militia attacked a wagon train passing through southern Utah.

The Fanchers were heading up the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation, pushing to make the area a national historic landmark. It was an effort they had worked on for years, but Jensen pushed it through, bringing all parties to the table.

Jensen and his associates went to the Fanchers' home, then visited other descendant families. During the ride, Jensen and Diann Fancher sat in the back of the truck, sharing Bible verses. Later, the Fanchers visited Jensen's Huntsville farm and went to LDS services with the family.

"The relationship really bloomed," Harley Fancher says in a phone interview from Arkansas.

When the two parted, Jensen asked, "Friends forever?"

Fancher replied, "Yes, sir."

What's next? For now, Jensen is happy to spend time with his wife, kids and 25 grandchildren. He's working the farm, catching up on his reading and doing some legal work to pay the bills.

In August, Republican Gov. Gary Herbert tapped him to serve on the Utah Board of Regents, overseeing the state's colleges and universities.

And Utah Democrats — intent on wooing more Mormons into their tent — have been after him to run for office.

Even the LDS Church's governing First Presidency greenlighted Jensen, once he gained emeritus status, to pursue politics, says Kathy Jensen.

So far, he has declined.

But, as that sage LDS leader once said, no one knows the end from the beginning.

About Marlin Jensen

• Born in Ogden on May 18, 1942.

• Served a mission to Germany

• Earned bachelor's degree in German from BYU and a law degree from the University of Utah.

• Married Kathleen Bushnell in 1967. They have eight children.

• Named to LDS Church's First Quorum of the Seventy in 1989.

• Served as president of LDS mission in Rochester, N.Y., from 1993 to 1995

• Appointed LDS Church Historian and Recorder in 2005. —

Jensen's accomplishments in overseeing the LDS History Department

• Construction of the new Church History Library in downtown Salt Lake City.

• Release of an online catalog to the church's historical collections.

• Mass digitization of the church's historical collections.

• Development of a digital records management system.

• Release of multiple volumes of the groundbreaking "Joseph Smith Papers."

• Strengthening of ties with others in the historical community.

Source: Richard Turley Jr., assistant church historian and recorder —

Conference weekend

LDS General Conference is this weekend at the Conference Center in downtown Salt Lake City. Saturday's sessions are at 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. with a priesthood meeting for male members at 6 p.m. Sunday's sessions are at 10 a.m. and 2 p.m.