This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Before he retired earlier this year, the Utah County corrections officer who gave a police report to Brigham Young University's Honor Code Office was accused by the state's police regulators of lying to their investigators.

Utah Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) sent Edwin Randolph a notice dated Jan. 23 accusing him of lying three times. Each count concerned Randolph's explanation for why he took a rape report to the university.

Randolph told officials at BYU he was concerned about the behavior of a student who said she was a rape victim, according to the notice from POST, but Randolph told investigators from the Utah County Sheriff's Office and POST that his concern was a BYU football player he suspected of "taking advantage" of the student. The football player is not named in the report.

Although the student is not named in the POST notice, she matches the description of Madi Barney, who has accused a man named Nasiru Seidu of rape. Seidu, who is not referred to by name in the report either, and Randolph knew each other through Utah County's Ghanese community.

Although Randolph did not challenge the allegations, he retired about 12 weeks after receiving the notice. He surrendered his peace officer certification two weeks after that. Relinquishing his certification ended the disciplinary proceedings, and officially left the allegations as only that.

Jeremy Jones, Randolph's lawyer, said his client retired because he had reached 20 years of service and was eligible for benefits, not because of the POST proceedings.

Had Randolph, 47, who was briefly charged with witness retaliation last year, not retired, he could have challenged the accusations in an administrative hearing. POST would have needed to provide, according to state law, "clear and convincing evidence" of lying.

Jones on Thursday said POST would not have been able to meet that burden.

"What my client told POST was accurate," Jones said, "and it was consistent with what he had previously told" investigators from the Utah County Sheriff's Office.

Jones was adamant that Randolph did not lie.

Jones insisted any discrepancies in what Randolph said can be explained by who asked the questions and the context in which they were asked. He also pointed out that his answers to investigators from POST and the sheriff's office may have been more expansive than what Randolph once told Provo because he was asked better questions in a setting that allowed him to more accurately explain the facts.

The POST and sheriff's investigators issued Randolph what's called a Garrity warning. It takes its name from a U.S. Supreme Court ruling saying that peace officers may be compelled to answer questions in an administrative investigation, but those statements can't be used to convict them of a crime.

Had he chosen to contest the POST case, Randolph would have risked a multiyear suspension of his police certification. Such suspensions often end careers as police chiefs or sheriffs are forced to terminate the officer and, after the suspension, potential employers are reluctant to hire an officer with such a discipline record.

The Salt Lake Tribune obtained the POST notice under a public records request. POST was the third law enforcement agency to investigate Randolph.

According to the POST report:

• After Barney told Provo police that Seidu raped her in September 2015, Seidu met with Randolph, who offered to help Seidu find a lawyer. Seidu gave Randolph the Provo police report to give to a potential defense attorney.

• Randolph was concerned about behavior by Barney discussed in the Provo report and contacted the BYU Honor Code Office to tell staff there about Barney. The Honor Code Office referred Randolph to the campus' Title IX Office, which oversees gender equity issues. Randolph read staffers there the police report and gave them copies.

• Provo police and Randolph's own employer soon heard about what Randolph did. In an interview with Provo police, Randolph said he thought Barney was lying about the rape and that BYU might suspend or "kick out" Barney.

• Randolph denied to internal affairs investigators from the sheriff's office that he reported Barney to the Honor Code Office based on her conduct, the POST report says, and instead said he sought to warn campus staff about the football player.

Randolph was charged with witness retaliation, a felony, Feb. 19, 2016. But Utah County Attorney Jeff Buhman asked a judge to dismiss the case five days later.

Buhman on Thursday acknowledged he compared what Randolph told Provo police and what he told investigators from the sheriff's office before deciding to dismiss the retaliation charge. Randolph's explanation that he was seeking to protect female students was a factor in dismissing the charge.

"I don't believe that was all that influenced my decision, but it was significant," Buhman said.

The POST report says investigators from there interviewed BYU staff and listened to an audio recording of what Randolph told Provo police. Randolph did not raise any concerns about a football player in those discussions, the POST report says. When the POST investigators interviewed Randolph, he continued to insist his concern was the football player, not Barney.

A trial on the rape charge against Seidu is scheduled to begin Oct. 10 in Provo.

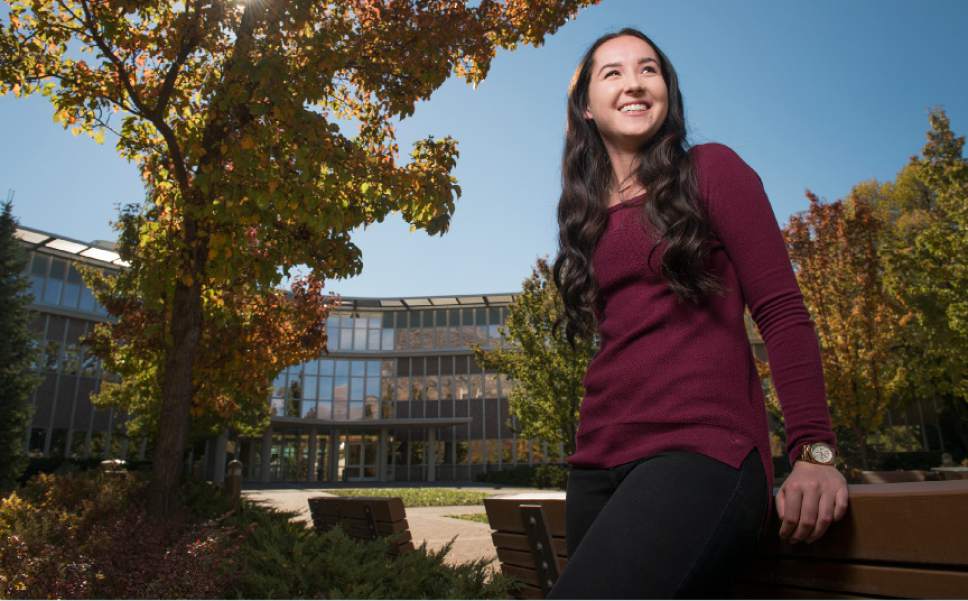

Barney has said BYU told her she would not be able to enroll in additional classes until she cooperated with an Honor Code investigation. She chose to continue her studies elsewhere and became an advocate urging BYU, which is owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, to grant amnesty from discipline for students reporting sexual assaults. BYU formally adopted an amnesty policy last month.

Barney declined to comment, citing Seidu's pending trial.

ncarlisle@sltrib.com

Twitter: @natecarlisle