This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Craig Watson said he didn't know if "closure" was the proper word.

But as he witnessed the 2010 execution of Ronnie Lee Gardner, who killed Watson's cousin Melvyn J. Otterstrom at a bar in 1984, a feeling of peace came over him: It was, finally, over.

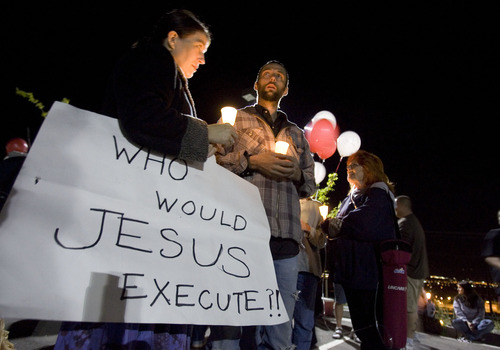

As Utah lawmakers weigh the cost of executing men like Gardner versus keeping them in prison for life, Watson asked them on Wednesday to remember there are some things that no amount of money can touch — a message also shared by Barbara Noriega, whose mother and sister were killed by another man now on Utah's death row.

"With the death sentence, there are no recurring offenders and we can go on with our lives," Watson said, his voice breaking at times as he addressed the Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice Interim Committee.

Rep. Steve Handy, R-Layton, asked for the analysis, the first study to examine what the capital punishment option costs the state and local governments. Handy has not proposed any legislation and said Wednesday he is "under no illusion that people in Utah want to change the present law." But Handy said the comparative costs of life without parole and the death penalty — which a legislative fiscal analyst pegged "unofficially" at an added $1.6 million per inmate from trial to execution — should be understood.

"Which direction citizens of Utah choose to go remains to be seen," Handy told the committee.

It is a topic of discussion in other states as well. New Jersey, New Mexico, Illinois and Connecticut all did away with the option in recent years. A year ago, Oregon Gov. John Kitzhaber put a moratorium on executions and ordered a review of that state's capital punishment law. On Nov. 6, voters in California, where more than 700 inmates sit on death row, rejected a proposition that would have repealed the state's death penalty; proponents argued for doing away with the option based on its costs.

Lawmakers may get some insight into Utahns' views of capital punishment from a survey being conducted by students at Utah Valley University under the direction of Sandy McGunigall-Smith, an associate professor of legal studies. The survey will be sent to 6,000 people randomly selected in Ogden, West Valley City, Kamas, Saratoga Springs, Alpine and Taylorsville.

Thomas Brunker, an assistant Utah attorney general, said the state has two policy interests in supporting capital punishment: deterrence and retribution. Gardner's case illustrated a "special" interest in assuring a condemned person could not kill again, he said, while the heinous nature of the crimes committed by other Utah death row inmates highlighted society's "right" to exact retribution.

Ralph Dellapiana, a defense attorney and death penalty project director for Utahns for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, said the cost estimates fall short of capturing the full expense of the dozen or so aggravated murder cases filed each year in which the death penalty is an option. Such cases require thousands of hours of extensive, multi-generational social histories of the offender, for example, costs that would not be incurred if the penalty were replaced with a life without parole alternative. The cost analysis also doesn't include expenses incurred in cases that are prosecuted as capital offenses but that end up in plea deals or acquittals, as occurred recently with Curtis Allgier, who shot and killed corrections officer Stephen Anderson during a 2007 escape attempt.

Without the death penalty, there would be faster closure for victims' families, he added.

And for offenders' families.

Peggy Ostler described the pain and emotional roller coaster her parents have experienced over the more than two decades that their adopted son, Michael Archuleta, has spent on death row. Archuleta tortured, raped and murdered Gordon Ray Church, 28, in 1988. The crime was terrible, she said, and life in prison would be appropriate, but facing their son's execution would be the "final blow" to her parents, who oppose the death penalty.

Watson agreed the legal process is too lengthy and often painful, an argument for streamlining rather than doing away with the death penalty.

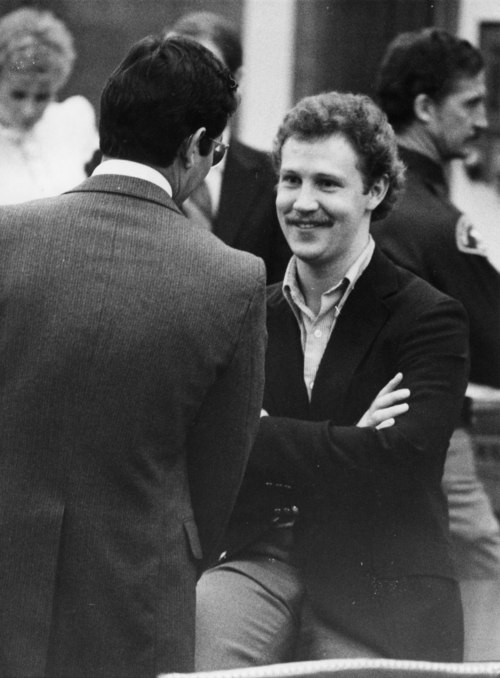

For more than two decades, as they waited for justice to be carried out, Watson said he and other relatives had every "stupid" move Gardner shoved in their faces — among them, feigned illnesses and escape attempts, including one at a courthouse in 1985 where Gardner fatally shotattorney Michael Burdell and wounded bailiff Nick Kirk.

"We got to hear about it, we got to see it, we got to relive it," said Watson, a 37-year veteran law enforcement officer.

Since Gardner's execution, Otterstrom's widow and son have finally been able to move on with their lives, he said.

"In my opinion, there isn't enough money to make a difference," Watson said.

Noriega placed framed photos of her mother Kaye Tiede, 51, and grandmother Beth Harmon Tidwell Potts, 72, on the table before her as she addressed lawmakers. Tiede had survived two husbands, both killed in automobile accidents, before marrying Rolf Tiede, Noriega said. The two built a cabin, which they called "Tiede's Tranquility," in Oakley as a family get-away and where they planned to spend Christmas in 1990.

Von Lester Taylor and Edward Steven Deli, who had escaped from a halfway house, broke into the cabin on Dec. 22, opened presents and waited for the family to return. Tiede, another daughter and Potts arrived first; the two women were shot and the daughter bound and gagged. Rolf Tiede and another daughter arrived next; he was shot and played dead as the two men set the cabin on fire and took off on snowmobiles with the younger daughters. Despite his injuries, Rolf Tiede managed to get help, and Taylor and Deli were captured.

Deli received a life sentence, while Taylor, identified as the shooter, was sentenced to death.

"There is no doubt that these savages did this to my family," Noriega said, calling the 22 years of legal wrangling that has followed "shocking, a travesty."

"It might be a lot of things, but it is not justice," Noriega said.

The family, once so wary of danger and crime, has had to confront evil and personal responsibility in "ways I never imagined," she added. "Our family feels the death penalty actually represents a reverence for the sanctity of the lives of the innocent."

Twitter: @Brooke4Trib —

Feugiat euismod ut wisi sed diam

Olendrem eugiamet dio dip et verit, vulpute cor amet velent am volesto odiamcommy nim dipit ut ullutet prate duisi. Rud dolobor suscidunt am, con heniamet illum nismodolore coreet. › XX