This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Darkness swallowed the room, tears filled her eyes and, for the briefest of moments, Mirta López had her daughter back.

"Sí! Sí!" she cried. "So beautiful."

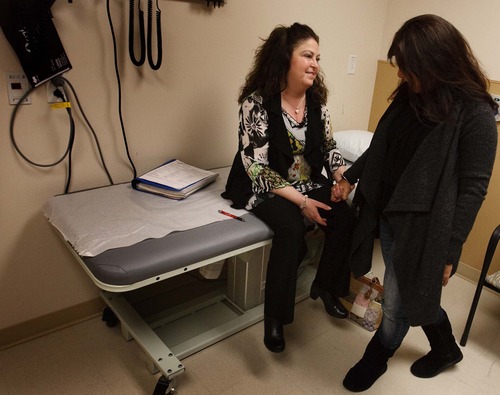

López watched the beating heart on the grainy echocardiogram — the screen's glow lighting her wide smile and glistening cheeks. In a chair, Pame Caballero, her youngest daughter, sobbed softly.

The technician steadied the wand on Allyson Gamble's chest as she lay curled up on the hospital bed against the wall. Gamble squeezed López's hand. Tight.

"She's taking good care of me," Gamble said.

"It was meant to be for you," López replied.

For the long minutes that followed, the two just gazed at each other. Mirta López had spent 24 hours on three flights across two continents to witness this — her daughter's heart giving Gamble life. López's joy, angst and longing were as inseparable as shades of mixed paint. After all, it was only April and she'd just buried her daughter about four months earlier.

The strong, steady pulse that once powered the body of 25-year-old Gabriela Caballero pounded rhythmically in Gamble's chest. The sound, amplified on speakers, filled the room. Gamble's husband ducked out for a fresh box of tissues.

Gamble locked eyes with López — mother to mother.

"Thank you," she said.

"Sí," López replied.

—

'I was in shock' • Headlights streamed along State Route 224 past the entrance to Canyons Resort at 5:25 p.m. on Dec. 10, 2011. It was Saturday night and Gabriela Caballero had just finished her day working as a ski concierge and was heading home to her apartment.

It was her third stint working at Canyons — the first being in 2008 — and it was a part of her ongoing love affair with the United States that began when she was a child. Those were times her dad brought back souvenirs from trips to America.

As a young adult, she had traveled to New York, San Francisco and San Diego, with scant interest in seeing other parts of the world. The trips to Utah began when friends who had worked in Park City on visas during the winter months would come back to Asunción and rave about the wide mix of shopping and restaurants. Her sister said Gabriela saw the Utah trip as a break from being a lawyer in Paraguay.

"This was fun for her," Pame Caballero said. "She worked hard and she loved being here."

Though she worked two jobs at times and the weekends were busy shuttling guests' skis or working as a clerk in the gift shop, she enjoyed her free time and was in a hurry to return to the apartment to get dinner.

But as she crossed the dark, busy highway, a southbound car never saw her and slammed into her small frame. The force of the impact was so great it flung her body into the northbound lanes, where another car struck her immediately.

According to the Utah Highway Patrol, she had been wearing dark clothing and was difficult to see as she tried to cross against the light. UHP officials also said she wasn't entirely within the crosswalk when she stepped into the road. UHP said the drivers weren't speeding.

Michael Serra, who worked closely with Caballero at the resort, said he didn't know what was going on when he saw the trail of emergency lights and traffic backing up that evening. It would be several hours before he learned it was his friend Gabriela, who was rushed to the hospital and died.

"I was in shock," Serra said.

In Asunción, López got a phone call in the morning as she was preparing food for a fundraising event at her evangelical church. López, a devout Christian, wept as the voice on the other end of the line told her what had happened. She would later liken the impact of the news to being thrown over a waterfall.

"The doctors told me on Sunday that she was declared brain dead and they asked me if I agreed with organ donation," López said. "They said that they were going to keep her on a ventilator and drugs until I could come and see my daughter."

The family arranged an immediate flight to Salt Lake City.

When López finally arrived — jet-lagged, sleep-deprived and numb — she was taken to her daughter.

What she saw was a battered, bruised, motionless body. She kissed her and stroked her hair. In that moment, she leaned heavily on her faith just as she had in 1993, when her husband died due to kidney failure — even after getting a transplant himself. He was the reason López believed in organ donation. He got three extra years with his family because of that kidney.

López braced herself.

"I saw the left side of her face and the doctors were taking blood samples and, inadvertently, moved her mouth open and that's when I realized it was not Gaby. It was only her body and she no longer had control of anything. That made me decide there — it was a very strong shock, and I said to the doctor, 'Enough already' so that wouldn't be the memory I had of my Gaby."

It wouldn't be.

—

Transplant families • For decades, contact between families of organ donors and organ recipients was rare.

LaRhonda Clayville, a nurse practitioner at the University of Washington, commissioned one of the first studies on families of organ donors who met recipients and said the practice was "virtually nonexistent" a decade ago.

The protocols tilt toward anonymity as both sides would write letters and use an organ-procurement agency as a go-between to communicate. It only takes one side expressing disinterest in meeting to shut down the process.

Throw in the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act — which has the effect of wrapping patients in a virtually impenetrable cocoon of privacy — along with vague information given to recipients revealing only sex and approximate age to further cloak participants.

But recently, the rise of social media and near-ubiquitous access to the Internet have turned curious families — both of organ recipients and donors — into cyber-sleuths parsing clues to solve the mystery.

Pam Albert, director of donor family services for New England Organ Bank, has been working on uniting families for more than 20 years and said that in-person connections still remain the exception rather than the rule — noting only about 5 percent actually end up meeting.

She said that's up from several years ago, when both sides might craft a letter to each other and give it to the organ-procurement agency. Often, that's where it ended.

"Now, between care pages, Facebook, Twitter or if it's a slow news week and there's a traffic accident story on the Internet, it's pretty easy to put things together," Albert said. "Sometimes people find out looking through the obituaries, too."

Dixie Madsen, public education supervisor for Intermountain Donor Services, said her organization usually recommends waiting a year for families to meet, though there are exceptions.

Clayville agreed.

"It's important to honor the grieving process and many people aren't ready to meet before a year, though there are some strong individuals who can," she said. "But I agree with the year wait."

Going back to 1988, there have been 1,028 heart transplants in Utah, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. In 2011, there were 36, including Gamble's.

Gamble and the López-Caballero family connected on Facebook a little more than a month after the transplant, though Gamble had already figured out whose heart she got. Just three days after her surgery, she had asked her dad to bring his laptop after asking hospital staff about the donor.

She was simply told the donor was a female in her 20s.

With the computer, she noted a news item about a woman from Paraguay named Gabriela Caballero killed in a traffic accident. Gamble figured she likely had her heart. But she didn't pursue it further until she got a call in January from Intermountain Donor Services saying the family of the heart donor would like to initiate contact.

Gamble said she didn't even wait to talk to her husband. She agreed right away.

"Suddenly, I had all of these [Facebook] friend requests from Paraguay and Peru — and I didn't speak Spanish," Gamble said. "It was the middle of the night and all of these messages started coming through. It was so beautiful — their outpouring of love and friendship — and they wanted me to know what an incredible person Gaby was."

—

Brown eyes, big smile • The big brown eyes were what most people noticed about Gabriela Caballero. Then the long, brown hair and the smile — a big one reminiscent of Anne Hathaway — that drew people in.

She was so popular in her Asunción neighborhood, more than 300 people showed up on Christmas Day for her funeral. She was buried next to her father, who died when Gaby was 7.

Not long after the funeral, Pame Caballero decided she would go to work at Canyons just as her sister did.

She arrived last week and, after a reunion with the Gamble family, began training for the concierge job. On a cold, rainy Sunday evening sitting in her small apartment, she gazed at pictures of her sister on her laptop. On her smartphone, she played "Paradise" by her sister's favorite group, Coldplay.

Pame Caballero remembered how her sister used to sleep with her when she was scared of ghosts. How they used to talk about boys and watch their favorite TV shows "CSI," "Grey's Anatomy" and reruns of "Friends." How Gaby, when she was 13, decided she hated cats after one came into the house and killed her parrot. ("We found the feathers. She cried," Pame Caballero said).

She smiled as she remembered how Gaby always — since she was a little girl — had a glass of chocolate milk for breakfast. Pame Caballero does the same. She still longs to hear Gaby call out "Pa-la-la" — her sister's nickname for her.

"I miss her on her birthday and on my birthday," Pame Caballero said. "But, really, I miss her every day."

The family still hasn't touched her stuff in her bedroom. Her clothes remain folded in the drawers of her dresser.

Her mother can't bear the thought of packing them away.

"It is like she is on one of her trips and is coming back," López said. "But I know she is not. But it strengthens us to see things as she left them."

Family members also draw strength from Gamble, who said she feels she's been given the gift of time with her 11-year-old son and her husband.

Gamble said she'd like to visit Paraguay and see where the López and Caballero families live and meet them. She'd like to let Gaby's heart go home for a visit. But travel isn't possible yet. Gamble still takes close to 30 pills a day as her body continues to adjust to the new organ. That's down from 60 pills after the transplant. She goes in every few weeks to have blood drawn, an adventure as nurses struggle to find strong veins not collapsed from repeated needle sticks.

At her job as executive director of the Capitol Preservation Board, she has to be aware of raised blood pressure and counts on co-workers to manage her stress levels.

She wants to be careful and make this work because, well, she's been through this before.

—

'You're going to die' • It all started with the flu more than 11 years ago.

Gamble was 32 and in great shape. She used a personal trainer regularly and her idea of a good time was rigorous hiking and camping trips with her husband, Jim. And, though the couple struggled to have a child, that changed in late 2000. For eight months, she coasted through her pregnancy.

Then she picked up the flu bug in 2001.

Gamble, not one to be slowed down, plowed ahead at her job and kept her busy schedule, even though at night she noticed her body reacting like a rubber band losing elasticity. After weeks of feeling under the weather, she eventually lacked energy to take off her shoes. An initial prognosis was dehydration, so she drank lots of fluids. She was also given an IV through a home-care nurse.

On the day Ben was born, the doctors gave her bad news. The flu virus had started an irreversible insurrection inside her body, narrowing arteries and slowing everything down while her heart ballooned to four times its normal size. Fluids were backing up in her system.

"You're drowning," the doctor told her.

But, more important, she was in the midst of heart failure — a condition she would cope with for about six years by taking a battery of medicines. By 2007, she was battling severe stomachaches and chronic heavy legs. Breathing was labored. She looked like she was pregnant again as her stomach swelled.

It was time to go to the hospital again.

Gamble said when she arrived, the doctor brought down the hammer: "You can't get out of this bed. You're going to die."

Two days later, on April 16, 2007, a heart became available and she got her first transplant. She never knew the donor. All she knew was the heart lasted for about a year before her body began to reject it. For the few years that followed until late 2011, Gamble's body steadily eroded the organ.

Gamble said she wasn't sure she'd get another chance. She had begun a few years earlier having difficult conversations with her then-7-year-old son, who had asked her if she was going to die. She vowed to "make memories" with him as much as she could.

"I think a lot about those times because that was scary, uncertain and a horrifying time," she said, "because I felt I wanted to see Ben grow and get to see him go to college."

Then, late in the afternoon on Dec. 12, 2011, while answering emails in her office at the Utah Capitol, the phone rang. The voice on the other end asked if she was sitting down. A heart had become available.

Would she like it?

—

The most beautiful things • The families sat out on the Gamble patio in Salt Lake City on a cool evening in April, and Yolanda Mohebbi, a longtime friend of Gamble, did her best to translate for López. It was difficult. Mohebbi cried as López and Gamble exchanged necklaces with hearts and stories about their lives. They wore bracelets that Gamble had inscribed to read, "The most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or touched, they must be felt with the heart."

Jim Gamble, who loves to cook, busily prepared a feast of salmon, soup and salad. Nancy White, Allyson Gamble's mother, effusively thanked López for her daughter.

Ben Gamble, a quiet boy, smiled shyly as López fussed over him and asked about his life. He told them about how he played soccer — a passion Gaby had — and how he liked school a lot. He said when they were all ready, he had been working for several weeks on a prayer that he wanted to say before both families sat at the table for dinner.

As they filed inside, they formed a circle in the living room and held hands. The boy, his hand quivering and voice cracking, looked down at his sheet of paper and began to read as quiet music played in the background.

"Gaby is now with us forever," he said, "but at the same time, she is looking down upon us in heaven with God. She will now rest in peace."

López smiled through tears. She held him tightly.

"Thank you for my mother," the boy said.

"Sí," she said.

dmontero@sltrib.comTwitter: @davemontero —

Organ donation facts

• An average of 18 people die each day awaiting a transplant.

• Each day, an average of 79 people receive transplants.

• 116,651 people are awaiting an organ.

• As of Nov. 30, 725 on organ wait list in Utah

• To register as a donor in Utah, visit http://www.yesutah.org/register

• To register as a donor outside of Utah, visit http://www.organdonor.gov/becomingdonor/stateregistries.html

Source • U.S. Department of Health and Human Services