This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

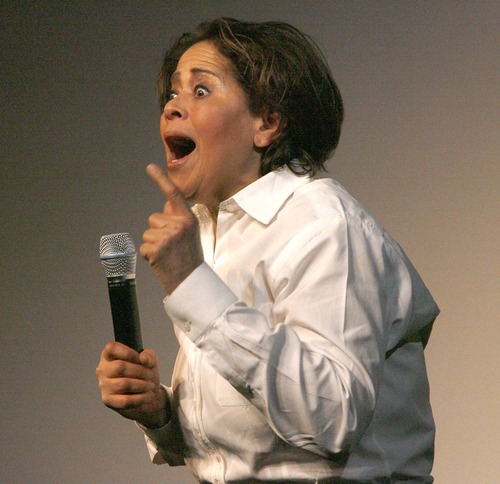

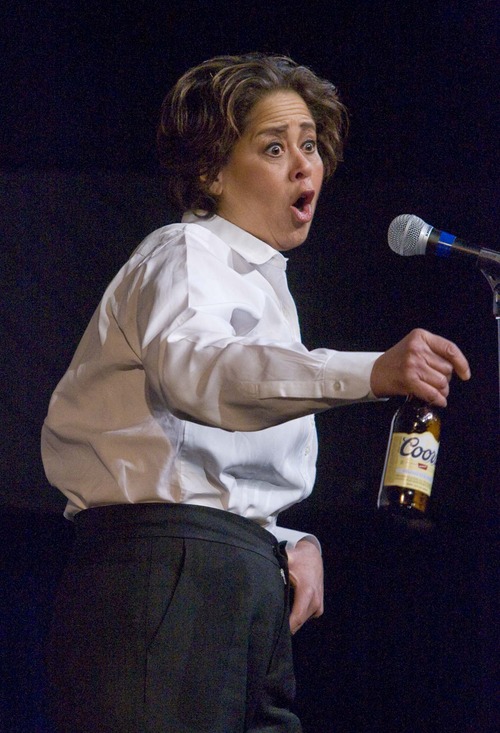

Some label Anna Deavere Smith as "an actor's actor." That implies a calibre of respect most theater professionals can only dream of. It's also another way of saying Smith is perhaps the best-known actor never to hit the pages of personality weeklies or gossip tabloids.

She'd no doubt take it as a compliment, but with a career as expansive and full of honors as hers, she's still more interested in testing the limits of her craft than notching up yet another award, such as her 1996 MacArthur Foundation "genius award" for creating "a new form of theatre — a blend of theatrical art, social commentary, journalism and intimate reverie," according to the fellowship board.

Screen appearances in Jonathan Demme's 2008 film "Rachel Getting Married" or his earlier 2003 film "Philadelphia" made Smith known to a wider audience. On TV, Smith is noted for playing a national security advisor on "The West Wing" and a hospital administrator in Showtime's "Nurse Jackie."

Yet it was her 1991 multi-layered one-person live show "Fires In The Mirror," in which she delivered a gallery of roles exploring tensions between Jews and African-Americans in Brooklyn's Crown Heights neighborhood, that first put her on the map as a theater force to reckon with. Since then, Smith has made several appearances in Park City at the Sundance Film Festival to promote films and perform.

While not officially on this year's festival schedule, she will perform a Saturday, Jan. 12 solo show at Park City's Eccles Center. She took a brief time out from her busy schedule, parking her car by the side of a California coast highway, to entertain a few questions.

You're credited as the originator of documentary theater, and as a pioneer in expanding the possibilities of theater. Do you believe there are any limits to what documentary theater can accomplish?

I don't know. The movement of documentary theater, verbatim theater, that worldwide movement is bigger movement than just me. These are nomadic people, working outside of institutions, who are trying to push expression and culture outside of the mainstream. The beautiful thing is that we're all bringing more experiences to the theater.

When I went to acting school, it reflected one thing — white males. I don't mean that as a political statement. It was fact. We studied and acted Arthur Miller, Ibsen, Chekov and Beckett. Certainly they're all giants of the theater, but that's just not where all people come from, even if we're talking about my [Baltimore] hometown. Really the only one outside that circle who was raised to similar heights was Lorraine Hansberry [ author of "A Raisin in the Sun"]. She died young, unfortunately, but at least she got there.

I think we'll have as much verbatim theater as these artists can provide, and as much of it as we need. My mother once said "If a baby cries, it needs to cry. So let it cry." I say, "Let the people speak, and let them speak as long as they want to speak and as long as they have audiences." Or as Cornel West said about Miles Davis hearing John Coltrane play for the first time, "Let the man speak. Let him speak his mind."

Even as I'm credited for this form of theater, there were people who came before. Studs Terkel was a pioneer who did it through journalism. The other is Spalding Gray, who was doing a different version of theater by telling his own stories, even if they weren't necessarily the stories of others. There were seeds of this before I came along.

Have you considered producing a documentary theater piece on our nation's debate over gun rights?

There's definitely a good piece to be made of that, but I can't do that right now because I've other projects going. I don't like to talk about things I haven't finished because it makes me feel I've done them when I haven't. That's a writer's temperament speaking.

Similar to many actors, you got part of your start in Shakespeare through the Riverside Shakespeare Company and the New York Shakespeare Festival. Has your view of the English-speaking world's greatest poet and playwright changed over the years?

A classical training is important in regards to simply learning about how dramatic language works. I got that attending the American Conservatory Theater. We still look toward Shakespeare to learn how to grow intellectually and dramatically.

However, I think there are elements of theater training that are changing, with new things to learn from. Acting on film has now influenced how we act on stage. Techniques of the "pure voice" on stage, whether you're studying theater of ancient Greece or early French theater, is no longer enough. Today, there's more that's required of your imagination. ... Technology has changed every way we think and learn about theater, the same way it's adjusting everything else.

At the same time, I don't think we can overrate Shakespeare's genius, but in a global community, I hope we'll be forced to learn about dramatic genius in other worlds beside the English speaking world.

What are three or four dramatic works you keep returning to, and why do you think you keep coming back to them?

Maybe I'd like to expand that beyond dramatic works. Picasso's "Guernica" has always been an influence. I love the works of composer John Adams, especially his short piece "Christian Zeal and Activity." I've always loved Edward Albee's "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" especially the film version. Works by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater almost always amaze.

Teaching is almost a work in itself. Every time I teach, I never know who's going to be there, or what they're doing to do. I know every single time I walk in the door, something extraordinary will happen. Somebody in that room will do something that's fabulous. Maybe I'll think it's fabulous, or another student will think it's fabulous. That's always exciting.

Your last big work, "Let Me Down Easy," explored sickness, mortality and the maddening details of our nation's health care system. Did you learn anything new or shocking to you in the process of creating that work?

I certainly learned the amazing ability people have to gather a story around what's happening to them. They quickly develop a really great narrative that helps them mend after they get catastrophically ill. That helps you learn a lot about human resilience.

When they [sick people] talk about the body's potential to heal, what I really heard was the voice of the healing spirt. That's very important in larger society, when we have a leader who's trying to heal the wounds of society. There are opportunities for collaboration that we don't always look for when we count on one person to do it all.

When I went to Rwanda to interview people there in the wake of genocide, people trying to find a way toward the healing of a culture and society, I found that same project on a national scale. It was a project bigger than life.

Do you have any special plans in mind for your Park City program?

Hopefully, just to delight the audience as best as I can!

Twitter:@Artsalt

Facebook.com/fulton.ben —

Anna Deavere Smith in Utah

When • Saturday, Jan. 12, 7:30 p.m.

Where • Eccles Center for the Performing Arts,1750 Kearns Boulevard, Park City.

Tickets • $20-$67; at 435-655-3114 or http://www.ecclescenter.org.