This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Midway • The dream for many of the filmmakers coming to the 2013 Sundance Film Festival is to receive standing ovations in Park City, land a multimillion-dollar deal with a Hollywood distributor, and launch a stellar movie career.

For the 300-plus attendees of the Art House Convergence, a gathering of independent movie theater operators this week, the dream is more modest. Show good movies, serve the community, and make enough money to stay afloat.

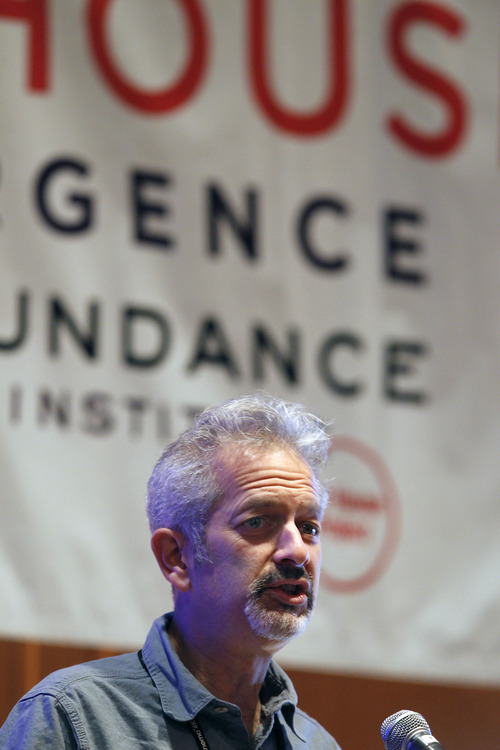

"The art-house movement is not going to create millionaires, and it is not the hot new thing that is going to transform media culture," said Russ Collins, conference director of the Art House Convergence, in opening remarks Tuesday at Midway's Zermatt Resort.

Art-house theaters — places that screen independent and foreign movies made outside the Hollywood system — do play a major role in a city's culture, Collins told those at the conference.

An art-house theater, he said, is "a sacred shrine to the most profound form of human expresssion created in recent times. … Your house is a key community institution. Feel it. Own it."

The Art House Convergence grew out of a meeting eight years ago, when the Sundance Institute called together a dozen art-house theaters to talk about common issues in exhibiting independent films.

"We started out as 20 people sitting around a table in the basement of the Peery Hotel," said Tori Baker, executive director of the Salt Lake Film Society, the nonprofit organization that operates the Broadway Centre Cinemas and the Tower Theatre. "We all said, 'What's going on with you?' "

"If you're an art-house theater, you feel kind of lonely and think you're the only one going through this," said Collins, who is executive director of the Michigan Theater in Ann Arbor. By meeting other theater operators, Collins said, people learn "they've got essentially the same problems you've got."

For the more than 300 people at the Zermatt Resort this week, many of those problems involve money.

In a survey of art-house theaters conducted by the Bryn Mawr Film Institute, a nonprofit community theater in Pennsylvania, 25 percent of those responding lost money in 2011. Eight percent broke even, while 33 percent made a modest profit (less than 10 percent) and 34 percent made a profit above 10 percent.

In presenting the survey, Juliet Goodfriend, president/CEO of the Bryn Mawr Film Institute, noted that theater operators say their biggest challenges are fundraising, attracting younger audiences, marketing their films, and converting theaters to digital projection.

"Your audience will pay for new seats before they pay for digital [projectors]," Goodfriend said. "You have to poke them in the eye, tell them, 'We go dark unless you give us money for digital.' "

The digital problem, Baker said, is that some movie distributors are no longer shipping out bulky 35mm prints — opting instead for digital copies of their films.

This new reality hit some art-house theaters last Halloween, when 20th Century Fox said it would send only digital copies of "The Rocky Horror Picture Show" to theaters aiming to screen the midnight cult classic. (Only five film prints were distributed by Fox, and the Tower got one of them.)

"Pretty soon, people will not be going to exhibit cinema without digital," Baker said.

The Salt Lake Film Society, Baker said, is aiming to install digital projectors in two of its seven theaters by the end of March, and "we will need some public support" to pay for it.

Another new world for art-house theaters is the drive by some filmmakers to bypass traditional distributors and put their movies in theaters themselves, one city at a time.

On one conference panel, veteran film booker Michael Tuckman described the experience of taking "Detropia," an atmospheric documentary about the decline of Detroit, on the road after its premiere last year at Sundance. He said that the film's producers hired publicists in only three cities — New York, Los Angeles and Detroit — and otherwise relied on theaters to drum up publicity for it.

That takes a commitment, Tuckman said, both from filmmakers to know their film's appeal and from theaters to know the local audiences. "If you're going to do this, you've got to go all in," Tuckman said.

Sometimes the theater can do that leg work. Michael Falter, programming director for the Pickford Film Center in Bellingham, Wash., said he visited every beekeeper in the area when his theater programmed the documentary "Queen of the Sun," about mysterious disappearances of honeybees across America. The contacts paid off, he said, and the movie ran successfully for a month.

Ted Hope, executive director of the San Francisco Film Society and a longtime independent movie producer, said that he has long predicted a fruitful collaboration between filmmakers and exhibitors. "There's still an incredible gap," Hope said. "[Filmmakers] want to know who these [art-house] people are, and develop a relationship."

It hasn't all been dry business talk at the Art House Convergence. On Monday night, attendees were treated to a sneak preview of one of this year's Sundance competition films, Shane Carruth's "Upstream Color." Tuesday night, appearances by Sundance Institute founder Robert Redford and actor/avant-garde filmmaker Crispin Glover were scheduled.

The conference runs through Thursday afternoon — just in time for everyone to head over to Park City for the film festival's opening-night festivities.

More Sundance in the Mix and online

See additional coverage on C1, and online at http://www.sltrib.com/blogs/sundanceblog.