This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court issued its Roe v. Wade and a second landmark decision 40 years ago preserving a woman's right to seek an abortion with limited restrictions, the Utah Legislature responded by passing an act diametrically opposed to the new law of the land.

In its pair of rulings on Jan. 22, 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down laws in Texas and Georgia — and thus similar laws around the nation — and found that women have a privacy right to abortion that could be balanced by state interest in protecting life that was tied to viability of a fetus.

But today, the nation remains as conflicted as ever about abortion and women's reproductive health rights; last year, 42 laws were passed across the states to limit access to abortion. And Utah's law remains among the most stringent.

Utah has had a law on abortion since 1876, when the territorial government made it a crime punishable by two to 10 years in prison to produce a miscarriage in a pregnant woman through use of any medicine, drug, substance or other means unless done to save her life.

Many Utah lawmakers figured the state's new Abortion Act, passed on March 2, 1973, would not withstand constitutional scrutiny — one section reinstated the previous law if the new statute were struck down — given the boundary the nation's high court had just drawn in its Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton decisions. But they forged ahead.

Tucked into a 142-page bill revising Utah's criminal code, the act allowed abortion only when necessary to save the life of a pregnant woman or prevent serious and permanent damage to her health. It required judicial hearings before all abortions and consent by the father; if the father was unknown or couldn't be located, the woman had to file a court affidavit swearing she had done her best to find him.

The law didn't stand long.

In August 1973, Roe v. Wade was cited by a three-judge panel in Salt Lake City's U.S. District Court in declaring Utah's new law unconstitutional.

The justices were ruling in a case brought by a woman identified as "Jane Doe" who was 11 to 15 weeks pregnant, on Medicaid and in need of a medically necessary abortion. The panel found the Utah Abortion Act, among other flaws, was discriminatory and overly broad since it applied to any trimester of pregnancy.

"The court finds that the overriding purpose and dominant effect of these statutes is the wholly improper one of making the obtaining or performing of an abortion in Utah extremely burdensome or impossible in every case," the court said.

Utah's federal court came to a similar conclusion, upheld in 1974 by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, in another case brought by three women known as Jane Doe, Jane Roe and Jane Poe. They sued the state over an informal policy requiring the director of the state Department of Social Services to personally approve an abortion for any woman receiving Medicaid. Approval was given only if the abortion was necessary to save the expectant mother's life or prevent serious and permanent physical injury — which the director found wasn't the case for the three plaintiffs.

The trial court judge found neither state nor federal policy supported such a stance and that the director did not have authority to deny payment for abortions. If the statute was unconstitutional, so was the informal policy, which the appellate court concluded was intended to limit abortion on moral grounds rather than any compelling state interest or rational basis.

The Utah Legislature formally repealed the act in February 1974 and replaced it with a statute that fell mostly in line with Roe v. Wade, though one section would be tested again in the courts. That section required a physician to notify the parents or guardian of a minor and the husband of a married woman before performing an abortion.

In 1981, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the parental notification provision in Utah's law in a case involving a pregnant 15-year-old girl, opining that while requiring notice, the statute "gives neither parents nor judges a veto power over the minor's abortion decision."

In the late 1980s, as the number of abortions in Utah reached what would become a historic high, state lawmakers once again began eyeing ways to tighten restrictions. A couple of lines in hand-written notes, made as Utah lawmakers prepared to draft what they hoped would be the nation's most stringent abortion law, stand out more than two decades later.

"Be reasonable, sensitive, move carefully and cautiously," wrote Janetha Hancock, then an associate general counsel for the Legislature. "Don't do everything all at once — one step at a time."

That advice — given to lawmakers and Hancock in 1989 by Lynn Wardle, a Brigham Young University law professor — fell by the wayside as some legislators pushed for a law they hoped would lead to a direct challenge of Roe v. Wade. The bill offered by Pat Nix, then an Orem representative, never got traction.

"I thought Utah was a pretty solid pro-life state, but it turns out it wasn't," Nix said last week.

R. Mont Evans, then a representative from Riverton, sponsored a more moderate abortion bill, but it also fell by the wayside as lawmakers waited to see how other states' laws weathered judicial scrutiny.

Evan Olsen, a representative from Young Ward in Cache County, took up the legislation again in 1991, co-sponsoring abortion legislation with former Sen. LeRay McAllister.

"We wanted a little more than Roe v. Wade," recalls Olsen.

Some lawmakers, as well as then-Gov. Norm Bangerter, balked at the stringent restrictions pushed by the conservative lawmakers and, in the end, the Legislature approved a watered-down version of what a task force had recommended, Olsen said.

"There were a lot of red-meat voices in those days saying we're tired of having the Supreme Court telling us what to do," said Wardle. "The goal was to go as far as we could go without transgressing the Supreme Court's decisions. The problem was the courts were continually shrinking that boundary."

On Jan. 22, 1991, pro-choice advocates sent miniature apple pies to lawmakers as they debated the legislation, proclaiming in a news conference that "choice is as American as apple pie." Three days later, Bangerter signed the Criminal Abortion Act, describing it as a "mainstream attempt to protect the sanctity of life without trampling upon the legitimate liberty interests of women."

Lawmakers also authorized a trust fund to accept private donations to help defend the new law, then the toughest in the nation.

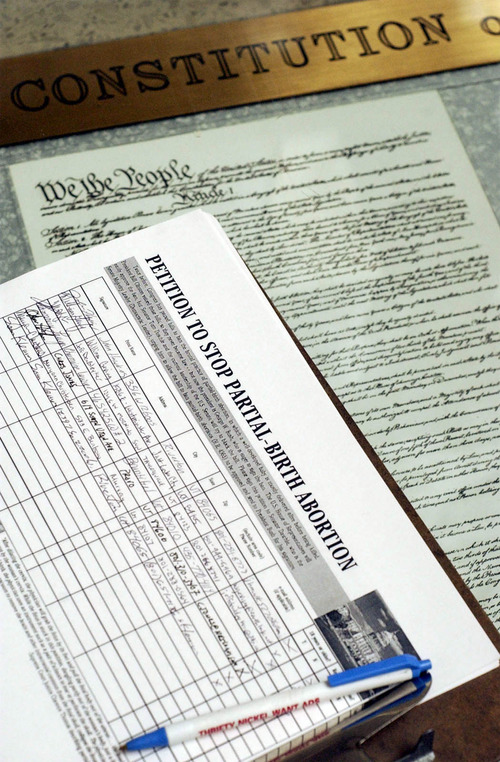

The act outlawed abortion with the exception of those necessary to protect the mother's health, save her life or for severe fetal deformity. It also allowed abortion during the first five months of pregnancy in cases of reported rape or incest.

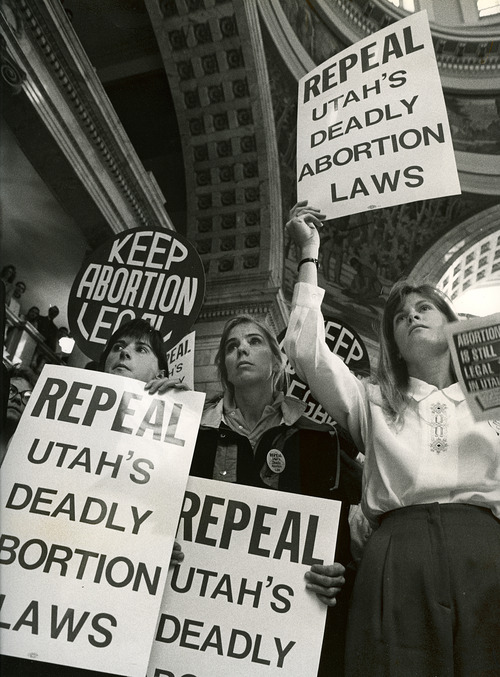

On Jan. 26, 1991, 2,500 people packed the state Capitol to protest the new law. They then marched to the governor's mansion on South Temple and hung coat hangers on the fence surrounding the home.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Utah filed a federal lawsuit challenging the statute that April. The ACLU also noted that by making most abortions illegal, the new law opened the possibility that a woman who had an abortion could be charged with murder.

The law was immediately stayed and in December 1992, U.S. District Judge J. Thomas Greene declared the law's ban on most elective abortions unconstitutional, while upholding a prohibition on most abortions after the 21st week of pregnancy. Greene also struck down a provision, in place since 1974, that required women to notify their husbands before obtaining an abortion. The 10th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the decision in 1997.

In the years since, lawmakers have followed the "one step at a time" advice with legislation that has narrowed and refined restrictions while focusing on a fetus as a living being. Women watch a video that shows a fetal heartbeat at incremental stages of pregnancy, for instance, and are told about state support and adoption options.

Utah is one of 24 states that earned an "F" grade this month from NARAL Pro-Choice America because of its stringent abortion law — a mark that Rep. Paul Ray, R-Clearfield, said means Utah is "sitting pretty good."

"I would take that as an 'A' for our efforts to protect unborn children," Ray said.

Utah is one of five states that require parental notice and consent before a minor may receive an abortion, with a judicial bypass when warranted. It is one of nine states that require pre-abortion counseling be done in person, and the only state that specifies that the counseling be "face to face." Utah is the only state in the nation that makes women wait 72 hours after counseling before an abortion may be performed.

"For women who live [in rural areas] that makes it exceptionally hard," said Karen McCreary, director of the ACLU of Utah, particularly for couples who learn their unborn baby has fatal fetal abnormalities.

Although pro-choice advocates talked about a legal challenge as the 72-hour wait was passed last year, they've decided against that strategy for now.

"I'm not sure that the court system is as willing to be the arbitrator in this whole challenge to reproductive rights and health care," with Karrie Galloway, director of Planned Parenthood Association of Utah. "With limited resources we had to make a decision about how best to accommodate the real needs of women and their families, and litigation wasn't it."

Abortion in Utah

The number of abortions performed in Utah peaked in 1989; it has remained around 3,200 per year since. In 2011, a majority of the Utah residents who sought abortions were single women between the ages of 20-24; about two-thirds of the abortions occurred between the fifth and eighth weeks of pregnancy.