This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Any day now, Addam Swapp — the central figure in one of Utah's most infamous events, a 13-day standoff at a rural cabin that ended with the death of a Utah law officer — will learn when he will be a free man.

It's been more than four months since a member of Utah's Board of Pardons and Parole held a hearing for Swapp at an Arizona prison, where a contrite Swapp pleaded for forgiveness and said he is no longer the defiant man he was so many years ago. At the end of that Sept. 27 hearing, board member Jesse Gallegos said he planned to recommend that Swapp be released.

"I just don't know when," Gallegos said. "It's clear, at least to me, that you have paid a significant price for what you did."

But Gallegos cautioned that he was just one voice among the five board members, who might not share his perspective that the time has come to free Swapp.

On Jan. 16 1988, Swapp set off 87 sticks of dynamite at the Kamas LDS Stake Center, blowing up the building. Swapp said at the time he was acting on a revelation from God and wanted to bring down The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and resurrect John Singer, his father-in-law.

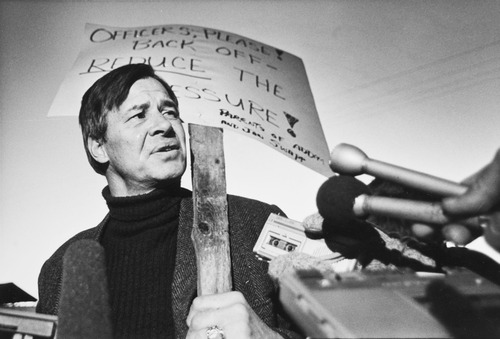

Singer, a fundamentalist Mormon, was fatally shot in 1979 after a yearslong feud with local officials that began when he and his first wife, Vickie, decided to home-school their children. Singer had taken a plural wife six months before his death. He was shot by officers who had come to serve him with a contempt of court citation at his ranch in Marion, Utah, after pointing a loaded gun at them while retrieving mail.

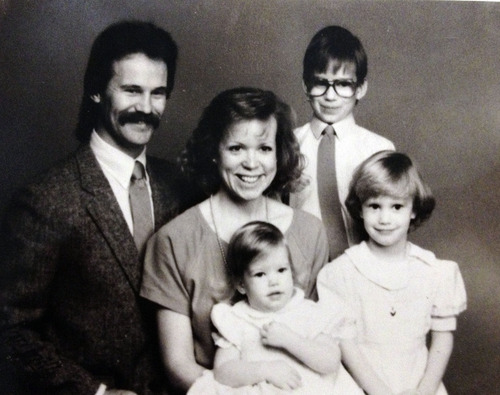

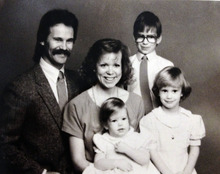

Swapp married one of Singers' daughters in 1980 and then later married another, living for a time polygamously.

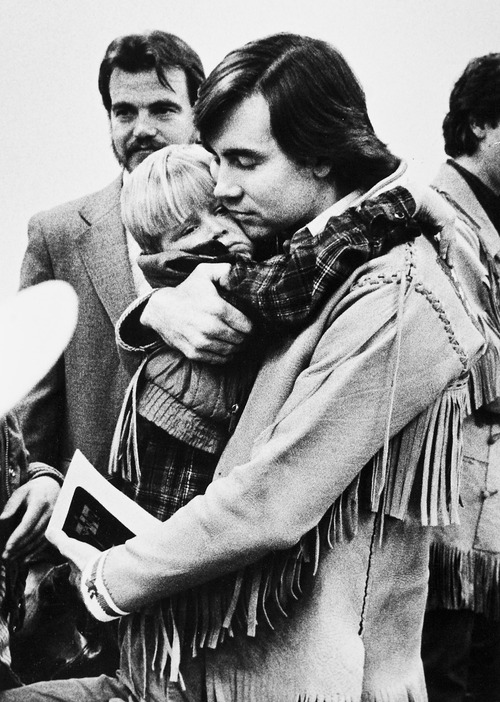

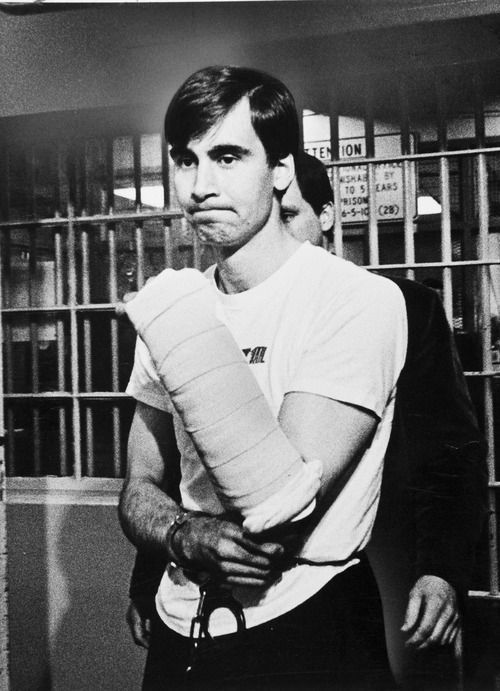

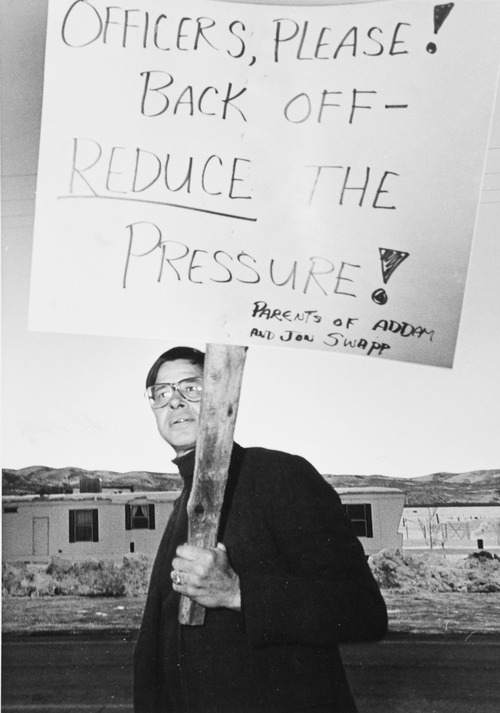

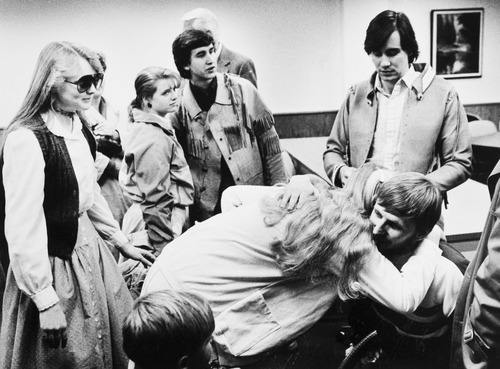

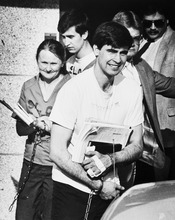

After bombing the LDS meetinghouse, Swapp holed up at the Singer ranch in nearby Marion with 14 other members of his extended family. The standoff ended when John Timothy Singer, Swapp's brother-in-law, fired a rifle as Lt. Fred House and another corrections officer prepared to release police dogs on the property. House was struck and killed. Swapp was wounded in the crossfire.

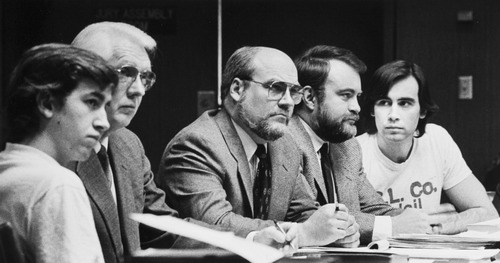

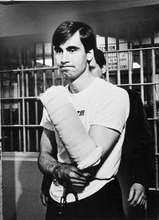

At his initial court appearances, Addam Swapp created a spectacle in a buckskin coat, made by his two wives, adorned with Indian signs, geometric symbols, nine feathers representing the years since Singer's death and, across the back, the "Banner of the Kingdom of God" flag Singer designed. In an interview with The Salt Lake Tribune at the time, Swapp said he believed he was chosen by God to gather the American Indians for the second coming of Christ and that the resurrected Singer would gather the other tribes of Israel.

Swapp, now 51, has spent close to 25 years in prison, nearly half his life. Under Utah law, an individual may not serve more than an "aggregate maximum" 30 years unless sentenced to prison for up to life, life without parole or death, though Swapp's sentence is not set to expire until 2020.

In 2006, Swapp completed a 20-year federal sentence, with time for good behavior included, for the bombing, armed resistance and attempted murder. He then began serving up to 15 years on a state manslaughter charge for House's death.

Because his crime involved the death of a law enforcement officer, Swapp is serving his state sentence outside of Utah; he is currently housed at the Phoenix Federal Correctional Institute.

The Utah parole board last reviewed Swapp's case in 2007. At that time, Ann House, Fred House's widow and mother of their three children, said she was not convinced that Swapp had taken full accountability for his actions or changed his ways.

But at the September 2012 hearing, Gallegos reported that House had sent the board a letter saying she now feels Swapp has served enough time — a perspective he said had the most impact on his decision to recommend that Swapp be released.

"She now accepts your apology," Gallegos told Swapp, "and feels that enough time has been spent behind solid walls."

During that Sept. 27 hearing, Swapp broke down at times as he expressed remorse for his actions.

Swapp said that in 1988 he had an "Old Testament" mind-set that focused on the "letter of the law, it wasn't about the spirit of the law." He also viewed authorities as "my enemies."

"What I've come to learn is that how I acted was completely wrong," Swapp said. "I should not have done what I did. If I could go back and redo it, I certainly would. ... My recourse now, if I was back there, would be to simply find another place to live."

Swapp said that during the standoff he shot out floodlights and loudspeakers set up by law enforcement to disturb the family's sleep at night, but never shot at or directed anyone else to shoot at officers.

"I was wrong in all my actions, but I can say with an open heart, I never did shoot at any officers," Swapp said. But he said he was taking full responsibility because "the whole thing was set in motion because of my actions, therefore I'm responsible.

"I have great remorse for causing those circumstances," he said.

Swapp said the years spent in prison had changed his "core beliefs" and allowed him to focus on the pain he had caused others.

"I don't think there could have been any other way to reach my heart," Swapp said, "[except] through this experience. The very center of my belief is in the person Jesus Christ and through his word the New Testament. That's the pebble dropped into the pond. I try to have my actions governed by that.

"I am fully determined to live a life of peace, to be a blessing to my fellow man, [so] when I finally am buried and people reflect upon my life, I want it to be not what happened in the year 1988 ... but the man that I've become since I got out of prison," Swapp said, weeping. "So I can be a blessing to my fellow man and that when people talk about me, it will be with love in their hearts, not as some radical, not as some fanatic, but as someone who truly represented the teachings of Christ. That's what I want with all my heart."

When Gallegos asked how long someone found guilty of taking a life should spend in prison, Swapp answered: "If his heart's been broken, if his spirit's been crushed, if he has humbled himself and he feels with all his heart and soul that what he's done is wrong, that is a great factor that has to be considered. If that person hasn't changed, I don't have an answer."

Swapp said, when he is released, he plans to join his wife, Charlotte, in Fairview, where his parents, a brother and other relatives also live. In prison, Swapp has worked as a computer quality-assurance clerk and said he hopes to parlay that into a job.

Swapp read a long prepared statement at the end of the hearing, breaking down in tears often as he apologized to all those affected by his actions. At the top of the list was the House family.

"I'm so very sorry for having caused your family such deep grief and pain for all these many years," he said. "I was so wrong in what I did by blowing up the church and by resisting arrest. I know now that you [Fred House] only wanted a peaceful end to the standoff. I'm sorry that I caused you to miss out in life with your family and their love and society, especially in the lives of your children and in the love and companionship of your wife."

To Ann House, who did not attend the hearing, Swapp asked forgiveness for the deep heartache and solitary burden of single parenthood brought on by her husband's death.

"I'm so ashamed for what I've done to you," he said. "I don't deserve it, but I pray that one day you and your family might find it in your heart to forgive me."

He asked Fred House's children, parents and siblings to also forgive him and then sought the same solace from his parents, siblings, wife and children.

"Mom and Dad, I'm sorry for all the heartache I've caused you for what I did and for the many years I've been in prison," Swapp said. "I've watched you grow old, traveling year after year, to all the different prisons I've been in all over the country, faithfully coming to see me, bringing my little kids with you. I've caused you to suffer so much. I'm so very sorry."

Swapp acknowledged the heartache and embarrassment his children and siblings had to weather because of his deeds. He thanked his wife for standing by him.

"I wish I could have given you a whole other life," Swapp said to Charlotte Swapp, who was in the audience. Swapp's first wife and mother of five of his children left him years ago.

He apologized to the LDS Church and to his neighbors and residents of Kamas for the "fear that I engendered by my wrong actions by breaking the law."

Swapp said he has "fully set my heart" on exercising the love and peaceful example set by Jesus in all his actions that "I might never again cause such hurt to another human being."

"I wish I held these beliefs back then," Swapp said. "I am so sorry for all the people that I have hurt, especially to Fred's family. I do hope that one day they might forgive me for what I have done."

Gallegos cautioned Swapp that his future adjustment back into society would likely be difficult. He also warned Swapp to be wary of the kind of erroneous thought patterns that got him into trouble in the first place.

"Whatever happens in your life," Gallegos said, "you do not want to start up with those type of very deep-held and radical thoughts because, Addam, I'm here to tell you, if you start that up again, you will be remembered as the person from 1988."

Twitter: @Brooke4Trib —

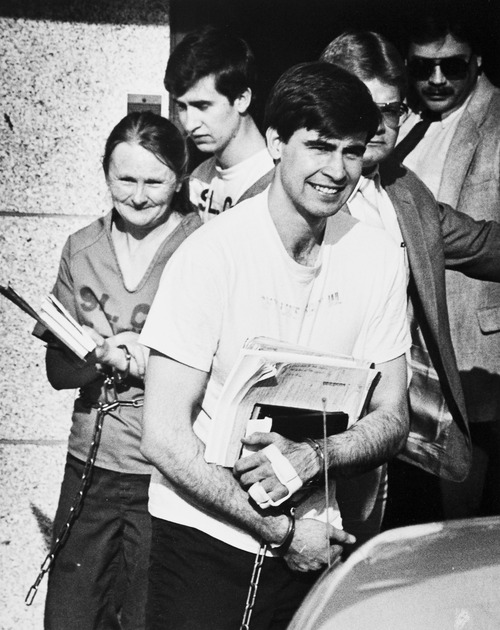

The standoff defendants

• Addam Swapp • Served 18½ years on federal charges for bombing of a Kamas LDS meetinghouse and Marion, Utah, and the subsequent killing of Corrections Officer Fred House during a 13-day standoff. Sentenced to up to 15 years on a state manslaughter charge.

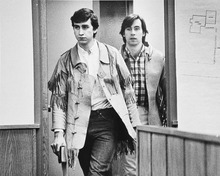

• Jonathan Swapp • Served eight years on federal charges related to the bombing and seven months on state charges of negligent homicide before being released in 1997.

• Vickie Singer • Served 3½years for aiding in the church bombing. She was released from prison in 1991.

• John Timothy Singer • A paraplegic, he fired the shots that struck and killed House. He served 18 years on federal and state charges and was released from prison Oct. 10, 2006.