This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

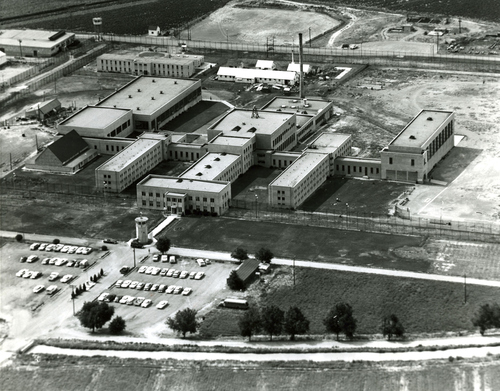

When Utah authorities moved 451 inmates from the old territorial prison in Sugar House to a new facility on farmland at the Point of the Mountain 62 years ago, it seemed they were transporting the convicts to the middle of nowhere.

Draper was little more than an unincorporated hamlet in 1951, far from Salt Lake County's urban center.

Today the Utah State Prison is as welcome as lint in what some now describe as the state's "belly button" — a thriving center of communities and high-tech businesses along the Interstate 15 corridor that state officials say is increasingly key to Utah's economic viability — and pressure is building once again to find it a new home.

"This is a special piece of property, maybe even in the sense of one of the few pieces in the United States of this size and in this kind of location that has ever been developed," Sen. Scott Jenkins, R-Plain City, recently told members of the Senate Judiciary committee. "It is that special."

The Prison Relocation and Development Authority (PRADA) that met last year concluded a confluence of factors — depressed construction costs, low loan rates, savings possible with a modern, efficient prison and high interest in developing the current prison site — made this an ideal time to undertake the estimated half-billion dollar project.

A bill to make that happen, sponsored by Jenkins, passed the Senate but has stalled in the House Rules Committee following criticism from pols and the public over composition of an authority to oversee the project, concern it is catering to special interests, and the project's costs and financing assumptions. Without any public discussion on the point, Jenkins introduced a second version of the bill on Feb. 25 that invited proposals from private operators interested in taking over the programming and operation of the new prison — language that did not stand out until Tuesday when Jenkins unveiled a fourth version that had been whittled from 30 to six pages.

A day later, House Speaker Becky Lockhart recommended putting the brakes on the bill as the Legislature enters its last week and instead taking it up during a special session.

"I personally have some concerns about how, in my estimation, this has gone rather rapidly," said Lockhart, R-Provo.

Jenkins has stated matter-of-factly that impetus for the project came from developers, which has only heightened concerns about potential conflicts and catering to special interests. One example: Senate President Wayne Niederhauser, R-Sandy, owns a real estate development business about four miles west of the prison; he once worked for former Senate President Al Mansell, a developer and partner in Point West Ventures, a consortium formed four years ago to advocate for the project. Jenkins himself owns a plumbing wholesale company, which he has acknowledged would "wipe me out" from serving on a committee that selects a bidder.

Nevertheless, Jenkins and some supporters insist there has been no fast-tracking, no lack of transparency and that the public and politicians will get the opportunity to weigh in before a final decision is made on whether to go forward with moving the prison.

But Steve Erickson, of the Citizens Education Project, says the process so far has been "bass-ackwards," without adequate public outreach or disclosure.

"The starting point should be, 'What do we want our twenty-first century Department of Corrections to look like?' " Erickson said. "If you begin with that, then you make intelligent decisions going forward, but if it is all about making a buck, you are going to stumble and fail to do the right thing. … What you want to look at is a range of options, and we haven't done that here."

Erickson believes step one should be updating the 2005 study by Wikstrom Economic & Planning Consultants, which concluded there was a $372 million gap between the cost of a new prison — which it said was $461 million — and value of the current site. (In an updated analysis of best relocation sites in 2009, Wikstrom said construction of a 6,000-bed prison would cost the state $984.6 million.)

The first Wikstrom study found that the quickest financial return would be to convert the current prison property into housing, which at build-out would generate $150,000 annually in property taxes for Draper. A longer-term return — and the option supported by Draper then and now — would be to convert the property to a "mixed-use employment center," which the study anticipated would generate $970,000 in revenue annually for the city.

"This site is an ideal location for a technology center," the study observed.

—

The numbers •That same claim is being made now to justify the project, which Jenkins describes as 80 percent about land development and 20 percent about moving the prison.

"Everybody gets fixated on moving the prison," said Jenkins, who has criticized the Wikstrom study as outdated and too narrow in its scope. "Moving the prison is a small part of this."

The financial windfall for the state now being touted is several orders of magnitude greater than it was in 2005 — despite the fact Utah, like the nation, is still recovering from the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

The Governor's Office for Economic Development has estimated that converting the current prison property to commercial use could bring up to 40,000 jobs and $20 billion in tax revenue over 25 years, justifying the expense of moving the prison. But redevelopment would not begin until a new prison is built and the old one torn down, which according to Wikstrom would take four to seven years.

Jenkins has told his colleagues that building a new prison would cost an estimated $550 million to $600 million. It would be the largest prison construction project in the country in recent years.

Iowa is nearing completion of a $130 million, 800-bed maximum security prison in Fort Madison that is slated to open in January. Pennsylvania authorities announced earlier this year plans to close two older facilities and relocate inmates to a $200 million, 2,300-bed prison completed last year. It also plans to spend $400 million on two additional facilities, each with a 2,000-bed capacity.

The current inmate population of the Draper facility is about 3,600.

Jenkins initially identified four funding "tools" to pay for construction of a new prison. Jenkins said the state could save $3 million per year in deferred maintenance on the current facility's aging buildings, the oldest of which were built in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Those structures include portions of the Wasatch cell block, kitchen, laundry, library, gymnasium and administrative buildings.

Construction at the prison has gone on almost continually since then, including approximately 14 buildings added in the past 13 years. That includes the addition in 2000 of the Lone Peak minimum security unit and two observation towers built in 2010.

Still, national experts say, a new, modern prison would undoubtedly be more efficient and more humanizing for inmates than the current, added-upon facility.

"The primary cost in all prisons is staffing, and new designs and technology can createprisons that hold the same number of people at lower costs," said Chase Riveland, a former corrections director for Colorado and Washington states and consultant.

Jenkins projects savings of $17 million to $20 million annually in labor and operational costs, achieved in part by cutting 315 employees.

The Department of Corrections was budgeted for about 1,100 people at the Utah State Prison in Draper in fiscal year 2012. Total payroll for the estimated 869 correctional officers and clerical staff, 162 clinical and 60 programming employees, was about $76 million.

Kelly Atkinson, executive director of Lodge 14 of the Fraternal Order of Police, which counts about 350 correctional officers as members, said he believes the staffing reduction could be accomplished largely through attrition given the high employee turnover at the prison. That said, Atkinson believes the projected savings is inflated.

"You don't know that [figure] until you know what kind of center you're going to build and if it provides the kind of protection Utahns have come to expect from their prisons," Atkinson said.

At the time of the Wikstrom study the prison employed about the same number of people, a number that has held steady despite an increasing prison population. The study said significant reductions in staff were unlikely because staffing at Draper is "extremely efficient."

There was one officer for every eight inmates in 2005; today, that ratio is one officer per 11 inmates, according to the department.

Funding for a new facility also would come from selling the 690 acres the prison now occupies, which PRADA estimates would generate $100 million to $140 million — a doubling of the minimum value placed on the property in 2005, years before the real estate market crashed.

In a best case scenario — lowest construction costs and highest property values — the state would have a $410 million gap to finance. It would take nearly 18 years for the projected savings in efficiencies and deferred maintenance to recoup that sum.

"We estimate there will be a small shortage," Jenkins said during floor debate Monday. "We don't know that for a fact because these estimates were given to us in a request for information, not a request for proposals. … No question there is a void there."

Jenkins' initial bill would have allowed the relocation authority board to divert up to 50 percent of tax revenue generated by any new development on the current prison site to help pay for a new facility. Lawmakers scrapped that provision, which they said circumvented the authority of local taxing entities.

"If it doesn't pencil without this tax increment funding, I really don't believe we should do it," said Sen. Mark Madsen, R-Eagle Mountain, who sponsored the amendment eliminating the tax increment funding.

—

Privatize? •The current version of SB72 requires bidders to identify how they would fund the project, including any financing they would make available, how much taxpayer money the state might need to kick in and bonding options.

The biggest case for being able to close that funding gap may come from private prison operators. At least three entities that either operate or partner with governmental entities to operate prison facilities have already expressed interest in bidding on the Utah project.

That option gained favor nationally through heavy lobbying at a time when inmate populations were rising rapidly, said corrections consultant Riveland.

"The experience over the past couple of years has leaned the other direction," he said. "They haven't shown they were doing it cheaper than the state, at least by much. … The trend is going the other way now for political reasons and financial reasons."

Problems at facilities operated by some private companies — inmate escapes, riots and service gaps, attributed largely to the quality of lower-paid staff — also have made the option a harder sell in most places.

Utah has already dabbled with privatizing some prison operations.

In June 1999, the state selected Cornell Corrections Inc. of California to build a 500-bed privately operated prison at Timpie Point in Grantsville, but put the unsigned contract on hold months later after a downturn in the prison population. The state eventually abandoned the plan, and in 2001 paid a $1.5 million settlement to the company.

Then, as now, there was no evaluation of the prison's short-term needs or of alternatives to building a new facility, Erickson said.

"It's a cautionary tale," Erickson said.

Management & Training Corp., a Centerville-based private company, ran the minimum-security Promontory Unit at the Utah State Prison between 1994 and 2001, when the facility was closed because of budget cuts.

Atkinson said his policeorganization strongly opposes any new move to privatize the prison, which typically entails a reduced staff and lower wages.

"At the end of the day, incarceration isn't about making a profit," he said. "It's about protecting the general public. … There are certain things that government does really well and there are certain things the private sector does really well, and this isn't one of them."

Utah's prison population is projected to continue growing at the rate of 132 inmates per year, bucking the national trend of falling rates of incarceration spurred largely by shrinking state budgets, changes in sentencing policies and the latest research findings on rehabilitation.

"Research shows there are better ways to provide safer communities than just incarceration," said Patricia L. Caruso, a consultant and former director of the Michigan Department of Corrections, which has reduced its inmate population by nearly 10,000 between 2007 and 2011. "We figured out that we needed to save expensive prison beds for people we are afraid of, not those we are mad at."

Twitter: @Brooke4Trib The prison relocation project

The Prison Relocation and Development Authority (PRADA) was created by the Legislature in 2011 and charged with determining whether moving the Utah State Prison is economically feasible. It gave the project a green light after reviewing the prison's current operations and preliminary presentations from six interested parties who responded to requests for information. Those meetings were closed to the public and none of the information they provided has been disclosed.

The entities that met with the committee and provided information indicating that relocation is feasible are:

Deseret Corrections Center of Bountiful • Represented by Thomas Mabey, of Sahara Construction, one of Utah's largest construction companies. Sahara offers design, build and management services and has built a wide variety of projects in Utah and other states, including EnergySolutions Arena, Miller Motorsports Park and the San Juan Detention Center in Aztec, N.M.

Carter Goble Lee (CGL) of Alpharetta, Ga., a Hunt Company • Represented by Buddy Johns. Carter Goble Lee, acquired by the Hunt Company last summer, specializes in planning, design, program management and maintenance of justice facilities.

Dewberry Architects Inc. of Virginia • Represented by Gerald P. Guerrero of its Sacramento office. It plans, designs, engineers, manages and consults on a wide variety of public/private sector projects, such as the Oklahoma Forensic Center.

The Molasky Group of Companies of Las Vegas • Represented by Richard S. Worthington. A real estate development and management company, it specializes in design, build, finance and lease-to-own public/private projects. It has built several correctional facilities in Nevada.

Corrections Corporation of America of Nashville • Represented by Lucibeth Mayberry. Founder of the private corrections management industry, it designs, constructs and manages prisons, jails and detention centers. It is the fifth-largest private corrections system in the U.S., with more than 60 facilities that house 80,000-plus inmates.

Point West Ventures of Alpine • Represented by Mike Sibbett, a former chairman of the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole. Other principals include Robin Riggs, who served as general counsel to former Gov. Mike Leavitt and as associate counsel to the Utah Legislature, and real estate agent Al Mansell, a former state senator. Point West is a leadership group that formed four years ago to bring together entities to evaluate and oversee the economic development of the prison property and the relocation.