This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

EskDale • Gov. Gary Herbert traveled West Desert backroads Wednesday listening to the opinions of Utah's Snake Valley residents on a proposed agreement with Nevada to evenly split this arid basin's ground water.

Flanked by key aides, Herbert sat in the front row of EskDale High School's auditorium as locals argued both ways, always with an eye on the larger concern of how to keep Las Vegas from sucking dry the valley straddling the state line.

"It's kind of an evil project," said Cecilia Phillips, speaking of the proposed $15.5 billion pipeline to siphon groundwater south to feed the big casino town's growth.

"It will ruin the area, and possibly turn the place into a dust bowl. The longer we can hold them off the better," said the teacher at nearby Garrison's elementary school.

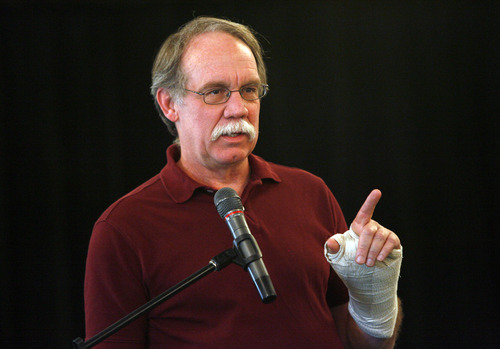

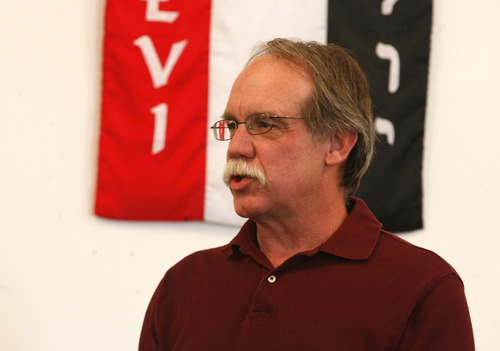

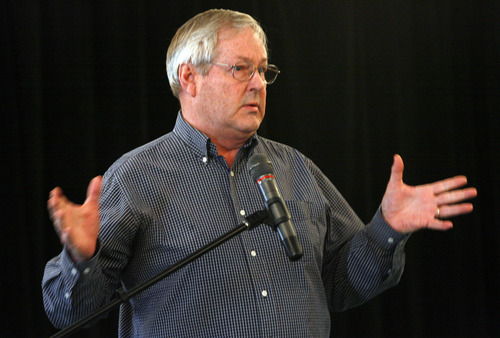

But the bi-state agreement, which the governor has sat on for nearly four years, contains substantial protection measures that would be lost if he refuses to sign, explained Mike Styler, director of Utah's Department of Natural Resources.

"Water is a significant and emotional issue," said Herbert, who indicated he will decide whether to sign by April 1. "It's our lifeblood. Our founding forefathers made this a great place to live because they learned how to capture the water."

The governor later convened a similar forum in Trout Creek at the north end of the Snake Valley.

EskDale is an agricultural hamlet of 65 on the Nevada border just north of U.S. Highway 6. It sits near the middle of the 120-mile-long valley that about 500 call home. To welcome the governor, the EskDale school's entire 24-student body sang two songs, including one titled "Wade in the Water."

Styler opened his presentation with strong praise for the young singers.

"It makes me want to cry," he said, before laying out what would happen if Utah rejects the deal with Nevada (on a red sheet) and what would happen if the state signs it (on green paper).

The green sheet set forth measures designed to protect Utah's interests and the ecological health of the valley, including provision to safeguard sensitive aquatic species.

"We cannot let the spotted frog and the least chub die out. They will get on the protected species list and we cannot let that happen," Styler said.

Under the agreement, pumping would be curtailed if the groundwater is being mined, that is withdrawn faster than it is recharged. If groundwater depletion harms the land, Las Vegas could risk losing the water rights.

"It does not give Utah consent to the pipeline or give up any Utah water," Herbert said. But without the agreement, Nevada is free to apply for the water rights now and develop them without considering Utah's concerns.

Earlier in the day, Herbert met with Millard County commissioners, who are unanimously opposed to the agreement.

"Once they start pumping that water, it's pretty hard to stop," said commissioner Jim Withers in an interview.

The EskDale audience showed solid consensus that the pipeline project should be impeded, but there was sharp disagreement over whether Herbert's signature on the interstate pact was the best way to safeguard the valley.

One tribal member said the native community was not adequately consulted when the agreement was crafted.

"This [pipeline] will destroy the lives the Goshute people and their nonnative neighbors," said Delaine Spilsbury, a Shoshone tribal member speaking for the closely related Goshutes. "Water is sacred to the natives. A lot of people when they see a running spring will stop and say a blessing."

Some felt the agreement legitimizes Nevada's claim to 35,000 additional acre feet of water annually from the valley, while others said the monitoring provisions could eventually prevent Vegas from ever touching the water.

Should Utah execute the accord, Nevada would agree to not even apply for the rights to Snake Valley for another 10 years, Styler said.

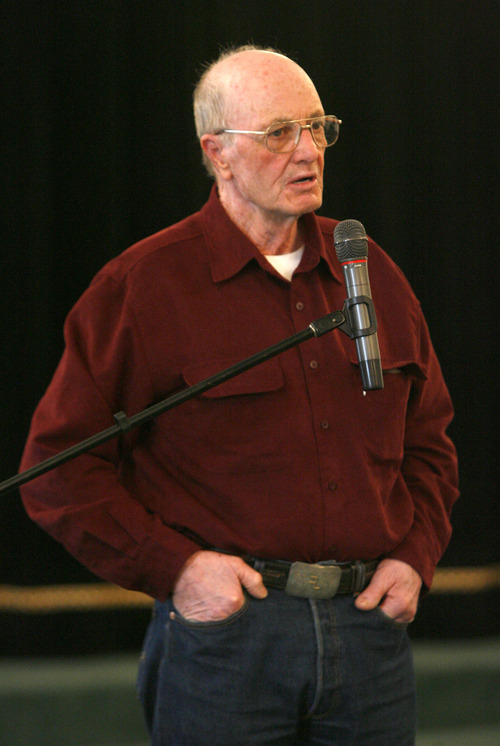

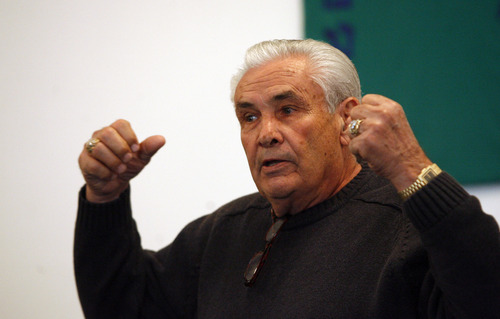

Members of the Baker family, longtime ranchers who work the valley on both sides of the state line, at first opposed agreement. But patriarch Dean Baker said it offers the best chance to kill the pipeline, or at least minimize its impacts on existing water rights and the landscape.

"It's a gamble no matter what we do," said Baker, whose three sons also ranch the valley. "The protection in this agreement is worth signing."

But many of the Bakers' neighbors disagree, and Baker acknowledged he was getting "hammered" for changing his mind.