This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

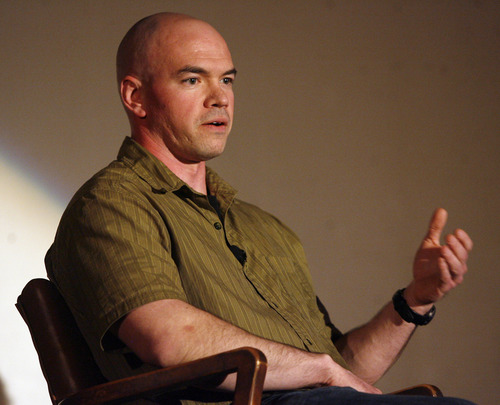

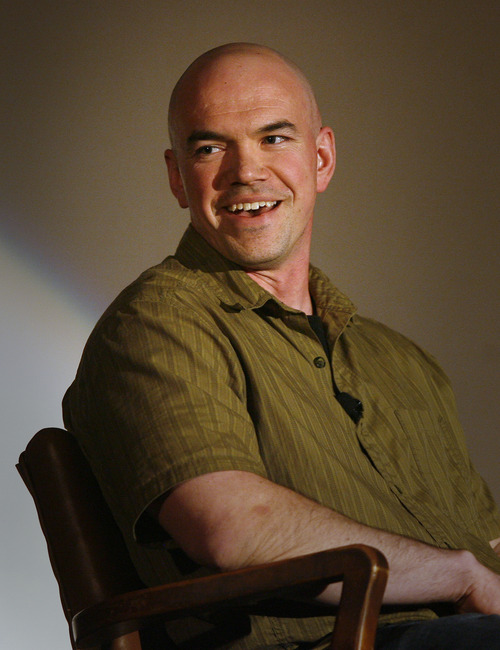

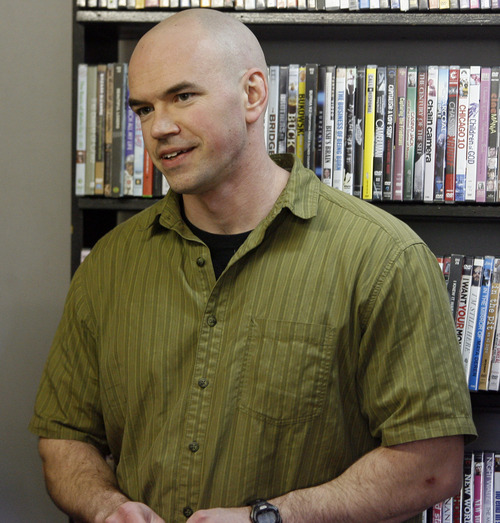

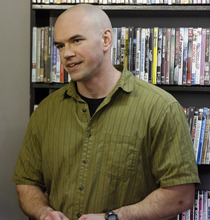

A hero's welcome greeted environmental activist Tim DeChristopher at an Earth Day gathering Monday night where he answered questions about his prison experience, the state of the environmental movement and his future, which is to take the University of Utah economics major to divinity school.

DeChristopher walked the streets of Salt Lake City a free man that day after spending the last 21 months paying his debt to society for derailing a federal oil and gas auction. His two-year sentence ended a few months early Sunday, and he remains on probation.

Yet he contends his punishment was the result of a rigged legal system so mired in technicalities and beholden to entrenched interests that it has lost sight of real justice.

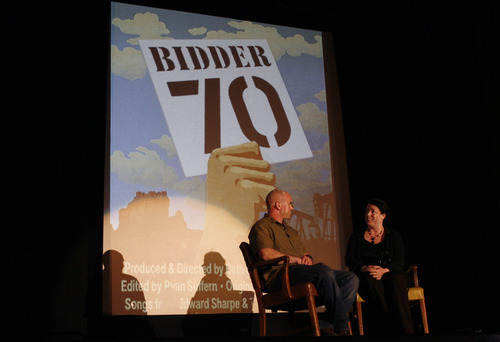

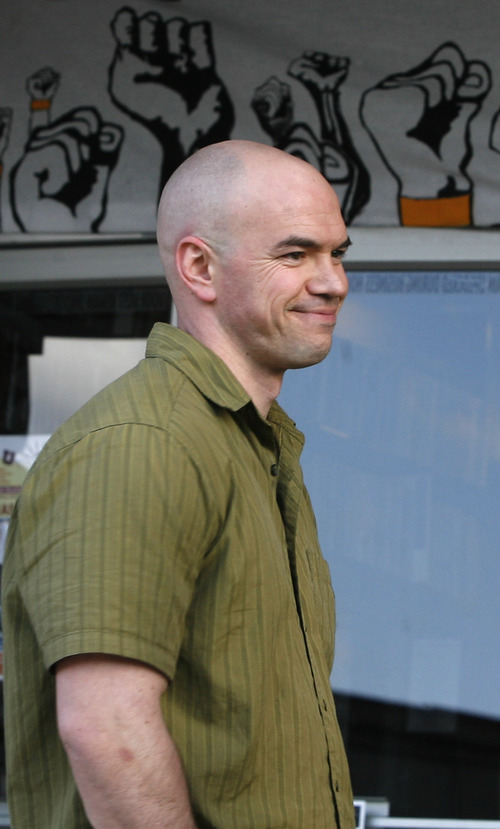

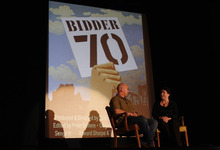

"Reform of the justice system is part of my activism moving forward. The right to a jury is an important element that has been lost," DeChristopher told well-wishers in a packed Tower Theater after they watched "Bidder 70," a documentary about his activism and prosecution. The audience regularly interrupted the show with cheers and whistles and many raised their fists in solidarity with the jailed activist as he strode to the stage after the lights came on.

"We are very interested in protecting the public lands," said attendee Joan Muschamp, a marketing consultant who moved to Salt Lake City from the D.C. area after DeChristopher went to prison. "We feel they should be maintained in public control so the people can enjoy them. A reason we moved here was the beauty."

The event marked DeChristopher's first public appearance since U.S. District Judge Dee Benson ordered him straight to prison. Filmmakers George and Beth Gage captured a shot of him being led from the courthouse in shackles and his pockets turned out.

The sentence triggered a demonstration and 26 arrests on Salt Lake City's Main Street. A jury had convicted DeChristopher of two felonies associated with the December 2008 auction, where he won 14 leases covering 22,000 acres for $1.8 million that he had no intention of paying. He was motivated to make the bids as a stand against human contributions to climate change.

Kathryn Casull of Salt Lake City believes DeChristopher never belonged in prison, particularly when the auction was later invalidated because the Bureau of Land Management had not properly reviewed the impacts of the proposed leases. Some covered breathtaking redrock country near Arches and Canyonlands national parks.

"He was standing up for our land," Casull said.

DeChristopher's remarks were live-streamed to 50 other sites where the film was screened for Earth Day and viewers posed questions in person and by Twitter. While many of the questions dwelled on how to invigorate environmentalism, the most popular Twitter query wanted to know what became of DeChristopher's dog Bernie, who appeared in the film.

"He lives pretty happily in Pocatello, Idaho, with my ex-girlfriend," he said. His immediate plans include a raft trip through Cataract Canyon and a canoe voyage on Minnesota's Boundary Waters.

"I'm going to have a good summer and after summer I'll move to Boston and go to Harvard Divinity School," DeChristopher said.

Since October he has been confined to a halfway house. His daytime hours have been spent working at Ken Sanders Rare Books, where he will make another appearance Friday to tell prison stories.

The thrust of his talk Monday was geared toward helping environmentalism get its mojo back, bend the political system to the will of people and explored ways to keep the economy churning without destroying our land and humanity.

Crucial to these goals are cultivating common ground with the many who believe the path to prosperity requires unfettered fossil fuel extraction, he said. That might mean investing in "genuine economic development" in rural communities dependent on drilling. But Americans have to curb their appetite for material goods, regardless of the energy sources used to produce them, if they expect their children to enjoy the future, he stressed.

"We must meet human needs with human interactions. It's a pretty simple concept. Most people across the political spectrum will talk about their human relationships, their communities," DeChristopher said. "We don't need to change these values. We need to reconnect with those values and get people to live closer to what their values really are."