This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

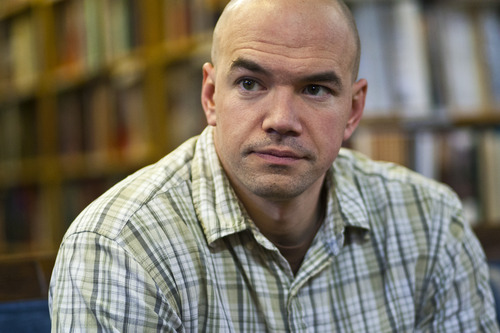

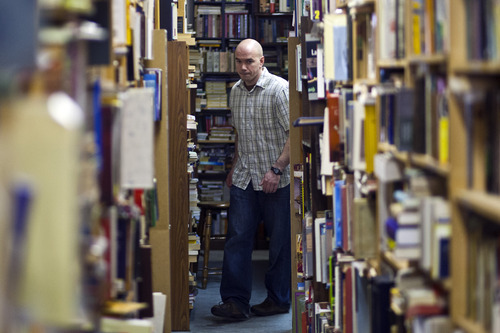

Now that he's free to speak his mind after serving nearly two years, eco-activist Tim DeChristopher wants to debate the role of juries with the judge who ordered him to prison for disrupting a government auction of oil and gas drilling leases in Utah.

At trial, U.S. District Judge Dee Benson instructed jurors to check their moral agency at the door, the jailed climate activist said Tuesday in an interview with The Salt Lake Tribune two days after his release.

This helped render his felony conviction a foregone conclusion, said the 31-year-old University of Utah graduate who is to attend Harvard Divinity School this fall while on probation. But DeChristopher was more dismayed at the sight of jurors agreeing to abandon their conscience and a judge confining his 2011 trial to a narrow set of facts that excluded the context and motivation.

DeChristopher's crime was posing as a bidder at a 2008 auction in which he won 14 oil and gas leases covering 22,000 acres, much of it near national parks. Not divulged to the jury was the fact that Interior Secretary Ken Salazar later invalidated the proposed leases because the prior administration failed to perform an adequate analysis of their impacts.

"The role of the jury is to protect our fellow citizens from the government. The jury is there to hold the government accountable," DeChristopher said. Instead juries have become a tool of government, he added.

He has no regrets for passing up a plea offer that would have imposed a month in jail. His lawyer Pat Shea had hoped to keep DeChristopher out of prison, arguing that he could do more to advance change as a free person.

"Politics is the art of moving people to the possible," Shea said Tuesday. "An activist always faces this challenge of where the line is drawn and, once drawn, are they going to cross over it. The result of crossing it would be to silence his voice. His voice was and is so strong."

But DeChristopher said he didn't want to cave in to what he viewed as a corrupt legal process that seemed more interested in deterring other environmental activists from engaging in civil disobedience than achieving real justice.

Besides, he believed he had a good defense if allowed to share his story with a jury of his peers.

"Plea bargains are a big part of the problem," DeChristopher said. "It cuts citizens out of the process and concentrates power in the hands of judges and prosecutors."

Benson wound up blocking his lawyers from raising a "choice of evils" defense, and then imposed a two-year sentence.

Many of DeChristopher's supporters, gathered Monday at Salt Lake City's Tower Theatre for his first public appearance since being ordered to prison, thanked him for what they regarded as a courageous sacrifice.

Even before he went to prison, DeChristopher was moving away from his street activism in favor of a spiritual path, citing his pastor, the Rev. Tom Goldsmith of Salt Lake City's Unitarian Church, as a crucial influence.

"I see divinity school and ultimately the ministry as an extension of my previous activism, not a new direction," he said. "I'm continuing on the path I've been on, just stepping my game up."

Although he hardly wanted to lose his freedom, DeChristopher said prison was not horrible. Frustrating and boring, maybe, but he did a lot of thinking at the federal prison in Herlong, Calif., and later at Englewood, Colo. He recalled eating fried green tomatoes soon after the first frost struck the inmate-run garden at Herlong.

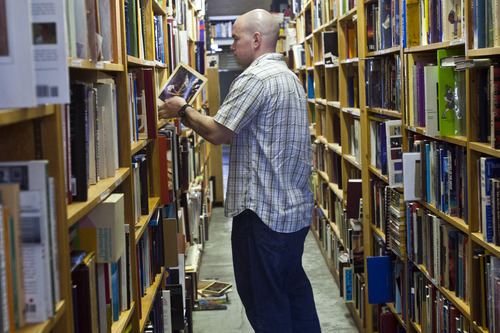

"I don't feel like I lost 21 months of my life. I lived 21 months of my life in prison, in a different environment. There is not much you have control over so there is not much to worry about," DeChristopher said. "A lot of my day consisted of walking the track and exercising and reading."

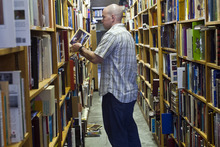

Among the books he read were Long Walk to Freedom, Nelson Mandela's 1995 autobiography; One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn; Winner-Take-All Politics by Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson; and The Value of Nothing by Raj Patel.

And he learned a lot about the justice system from fellow inmates, particularly one with a young daughter serving a minimum-mandatory sentence of 15 years for growing marijuana in his basement. Complicating his case was the presence of firearms in the house, although the weapons were legal and secured.

DeChristopher's Herlong cellmate described to him how we he was told to expect 30 years if he took his case to trial.

"His attorney said, 'You will lose,' " DeChristopher said. "It is taken for granted by everyone in the legal system that a defendant will be punished severely for exercising your right to a jury trial. You can still get a jury trial, but you'll get an extra 10, 15 years. If you are punished for exercising a right, then that's not a right."

He was puzzled that no one associated with his own prosecution, other than the probation officer who prepared his presentence report, made any attempt to understand him or his motives.

Before sentencing, where Benson pronounced DeChristopher "an enigma," the judge never looked the defendant in the eye, according to DeChristopher.

"We have been in the same room for dozens of hours and you have never asked me a question," DeChristopher said. "He said, 'I don't understand you,' and yet here's your sentence."

Trib Talk video online

To watch a video of Tim DeChristopher answering questions from viewers of Tuesday's Trib Talk, go online to http://bit.ly/ZHh7ad.