This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

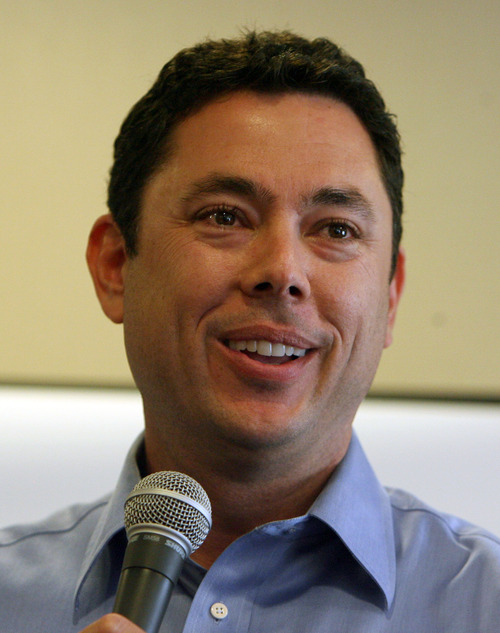

Hoping to shrink the glut of low-risk federal inmates consuming tax dollars in prison, Rep. Jason Chaffetz is about to unveil a post-sentencing reform bill that would allow drug offenders and others to earn early release into halfway houses, home confinement and ankle-bracelet monitoring.

Quietly, the Utah Republican has worked Washington's back channels for 18 months to forge bipartisan support. He insists the program — vetted by the Heritage Foundation and the ACLU — would reduce recidivism, lower crime rates and rein in spending on the federal prison system.

"There's some really good work being done by states that we ought to learn from," Chaffetz told The Salt Lake Tribune editorial board this week. "It's a financial imperative, it's a moral imperative — it just makes a lot of sense."

The challenge, Chaffetz concedes, is assuring the political right the measure isn't soft on crime, while convincing the left it goes far enough — short of unwinding mandatory minimum sentences.

"The risk, if there is with this, is the over-simplification," the congressman said, bemoaning bumper-sticker politics. "It does take some explanation. It does take an adult conversation to say, 'folks, we can do this.' "

The proposal marks a pivot for Chaffetz, whose more partisan turns with conservative media include talk of impeaching President Barack Obama regarding recent investigations, including the embassy attack in Benghazi, Libya.

—

Low risk? • The program would work by dividing federal prisoners into high, moderate or low risks of recidivism. They would be judged by level of engagement in existing programs, holding prison jobs and participation in faith-based services and educational courses.

Low-risk inmates would earn 30 days credit per month, moderate would notch 15 days, while high-risk convicts could get eight days worth of credit. Only low-risk prisoners would be eligible for pre-release custody into a halfway house, home confinement or ankle-bracelet program.

Prisoners convicted of violent felonies, terrorism, rape or a sex offense against a minor would not be considered. Neither would undocumented immigrants, an "albatross" and too touchy a topic, Chaffetz says.

The measure neither reduces minimum sentence time nor impacts Truth in Sentencing requirements. That's because 85 percent of each federal sentence still would be completed as mandated — though some of it could be outside the prison walls.

Paul Cassell, a former federal judge who teaches law at the University of Utah, says the program could be novel.

"It's very meaningful," he said. "Even if it tweaks the numbers by a few percentage points, that could add up to big bucks."

Cassell says the key is finding a method that targets the right people so it doesn't become a get-out-of-jail-free card. It is a "myth" that federal prisons are filled with nonviolent offenders who don't belong there, Cassell adds, while he says it's certainly true many sentences don't match the crime.

"It's going to be the Goldilocks problem here: Can we get it not too hot and not too cold?" he said. "Can we find the people with a low risk of recidivism and release them?"

—

Minimum mandatory? • Brett Tolman, a former U.S. attorney, remembers how inflexible the federal system seemed when a young man "who had a bad weekend" with drugs was slapped with a 35-year minimum sentence.

Then there is Utah music producer Weldon Angelos, who had no prior criminal record and now is considered a casualty of the war on drugs. Convicted in 2003 while he was in his early 20s of selling small amounts of marijuana — a witness claimed he had a gun on his side — Angelos was sentenced to 55 years under federal minimums. Cassell, the judge in the case hamstrung by the law, urged President George W. Bush to commute the sentence, calling it "unjust, cruel and irrational."

Dozens of former federal judges and prosecutors, including former Attorney General Janet Reno, signed a friend of the court brief saying the sentence is unconstitutional. Angelos, who won't be released until 2051 when he's 72, lost his appeal in 2011 and the Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

"We've got to fix the front end," said Mary Price, vice president of the nonprofit Families Against Mandatory Minimums, which is still reviewing the Chaffetz bill. "We're still pouring thousands of people into prison every year for sentences that are frankly too long."

Karen McCreary, executive director of ACLU of Utah, says she too would like to see reform to mandatory minimums but is intrigued by Chaffetz' bill. "The drug wars have made our system so full, so this is a positive," McCreary said. "It seems like a good step in the right direction."

—

'Attitude adjustment' • Because of mandatory sentencing laws, the population of federal prisons has increased almost tenfold since 1980, according to a report by the Urban Institute. This degree of crowding "threatens the safety of both inmates and correctional officers, and it undermines the ability to provide effective programming."

The report notes half the drug offenders sentenced in 2010 were in the "lowest criminal history category."

The Chaffetz proposal is modeled partly on Texas, which became the first state to complete a so-called "justice reinvestment" process, saving the state $1.5 billion in construction costs and $340 million in averted operating costs.

Tolman told the editorial board it's time the feds learned effective prison models from states like Texas. "We've always been arrogant and felt that we can do things better," Tolman said. "Either we're so large and cumbersome that we can't, or we're so ignorant and stubborn that we won't."

Expected to cost $100 million to $300 million, the program would be phased in over five years starting with 20 percent of prisoners the first year. Pre-release would not be automatic, rather subject to approval by the prison warden, chief probation officer and original sentencing judge.

Chaffetz says the savings would go toward prison programs and jobs as well as FBI agents and deficit reduction.

"Ninety-nine percent of [drug convicts] are coming back out," he said. "So we need an attitude adjustment about them."

Twitter: @derekpjensen