This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Kristell Thomas has been down this road before.

She spent several years in prison, went to the Orange Street Community Correctional Center in Salt Lake City, got out, got in trouble again and landed back in prison last summer. In January, Thomas returned to Orange Street, Utah's halfway house for women offenders and is now preparing to leave again.

For good, she says.

"I'm just finished," she said. "I'm done beating myself up. I'm done breaking my family's hearts. I want a good life."

Figuring out how to keep women like Thomas from coming back to prison is a priority for the Utah Department of Corrections, which has seen the female inmate population consistently exceed capacity — the point at which 96.5 percent of the 671 beds allocated for women are occupied — during the first half of 2013. In May and June, it even surpassed the 671, forcing the prison to dip into surplus funds to house women at county jails.

At the start of the new budget year in July, the department received more money to contract for county jail beds and used some of it for female inmates, easing the crunch — for now. As of Friday, there were 655 female inmates in state custody, down from 689 in June. There are 2,984 women on probation and 406 on parole.

Utah is not alone in experiencing an increase in the number of women incarcerated. The Sentencing Project, a national nonprofit organization, reported earlier this year that the female prison population nationwide rose 22 percent between 2000 and 2009, outpacing the increase in male inmates.

There are approximately 205,000 women in prison or jail across the country; another 815,000 women are on probation or parole. The Sentencing Project attributed the increase in female inmates to "get tough" sentencing laws and "war on drugs" policies.

While Utah also is seeing that effect, administrators have determined two factors are behind the recent crush at the prison: More women are "terminating" their sentences in prison without being paroled and more women are being sent to prison for repeated probation violations — such as failing drug tests and missing appointments.

The number of women sent to prison for violating probation increased 180 percent in the first quarter of 2013 compared to the same period in 2012.

"They are not coming back for committing new crimes," said Mike Haddon, a deputy director for the Utah Department of Corrections. "That is actually decreasing a bit."

The increase in women sent to prison after failing probation, as well as those who violate parole conditions, is partly why more than twice as many females now finish their sentences in prison compared to 2005. Jim Hatch, spokesman for the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole, said the numbers reflect a growing intolerance for probation and parole violations.

"If someone comes to prison for the first time and has a history of violating probation, and can't demonstrate that he or she could be successful on parole in the future, the board is simply having such offenders serve their sentencing guideline, or longer, up front," he said. "Likewise, with repeat parole violators, the board is now more quick to terminate their sentence from prison after fewer parole attempts ... rather than indulging a revolving door of people returning with technical parole violations."

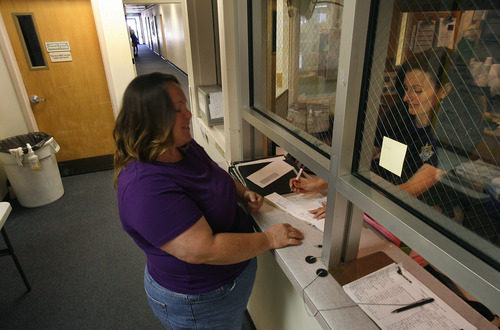

Orange Street Director Carrie Cochran said the 60-bed center, which takes offenders who need treatment, lack support or have no other place to go, has been at capacity for at least nine months. That has created a bottleneck at times between women ready to venture out on their own and those ready to transition from prison to the halfway house, something Cochran said the center has tried to better coordinate with the board. Some women stay at Orange Street for as briefly as a week; a few have been there as long as nine months. They receive a variety of services, in addition to room and board, for which they pay $6 a day.

"A lot of them are scared to get out," Cochran said. "They know what is expected here and it's safe."

Here's how Tasha Vincent, 31, put it on Thursday as she and two other women prepared dinner in the kitchen at Orange Street: "This place has been huge for us, to slowly reintroduce ourselves back into society and do it right."

Vincent will leave the center in early August.

Bonnie Leavitt, 47, said the thought of going straight back into the community after four years in prison was "almost overwhelming."

"A lot of things are pulling at you that you're not ready for," said Leavitt, who asked the board to send her to Orange Street, where she will remain until the end of the year.

Like Leavitt, Thomas asked the board to send her to Orange Street.

"I'm glad I came here because it gave me a chance to get my bearings and priorities in line so I [won't] be dependent on anyone else," said Thomas, 44.

But the ultimate answer is figuring out how to reduce recidivism among women probationers — which now hovers at 54 percent — so they don't end up going to prison in the first place, said Wendy Horlacher, a regional administrator for Adult Probation and Parole.

"Because it has become as critical as it is, we are looking at it in a new way," she said.

That is, in a gender sensitive way.

In May, the department applied for a $750,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Justice to fund a new three-year pilot it has dubbed the "Female Offender Success Initiative" (FOSI). The department, which will contribute $6.4 million in staff and other resources to the project, expects to learn any day whether it has received the grant. It anticipates more than 3,000 women will be served in the program.

Until now, the department's gender-specific moves have focused on female inmates and parolees. Six years ago, it adopted female uniforms and ended the practice of giving incarcerated women hand-me down male uniforms — many of which were stamped with the male offender's name and prison number. It also stopped giving female inmates men's shoes, available only in sizes 8 and larger.

Women now are fed a diet tailored to their needs rather than the 2,600-calorie-a-day diet designed for men they once received, which frequently led to weight gain that caused self-esteem issues that often triggered relapses. The prison also now offers substance-abuse programs and parole services designed specifically for women.

The proposed initiative is aimed at developing similar gender-responsive strategies to help women on probation stay out of prison, said Holli Simmonds, a staff supervisor at Orange Street who wrote the FOSI grant. Among its elements:

• Implementing a new Women's Risk Need Assessment tool developed at the University of Cincinnati that has been credited with helping reduce recidivism 20 percent in three states that used it to identify high-risk offenders who need more intervention. Currently, the department uses a gender-neutral assessment program.

• Collaborating with courts to adopt sentencing, probation conditions, penalties, rewards and sanctions geared specifically for women.

• Providing ongoing, statewide training about trauma, a factor underlying most women's criminal behavior, to corrections staff and others who work with female offenders.

• Improving collaboration with community partners and service agencies — from the Division of Child and Family Services to the Utah Housing Authority — that work with female probationers.

The challenges for women on probation and parole are immense, from finding affordable housing to staying employed. They are required to work 32 hours a week, but most end up in low-wage jobs that make paying for housing, child care and other expenses difficult. Since 2008, when increased demand from homeless clients caused the Fourth Street Clinic to cut off male and female probationers and parolees, helping women get health care also has been hard.

"The most difficult population are those who need social or state support," Horlacher said. Some have medical and mental health issues that make them unemployable. And they can't qualify for public assistance while living at Orange Street, she said.

"We've lost so many options out in the community, it makes it really difficult for women in transition," Cochran added.

Women who have completed their sentences or probation no longer qualify for the department's aid accessing services, which also makes them vulnerable to relapsing.

"We're trying really, really hard to expand services so they can continue even if they are not being supervised by us," Simmonds said.

Twitter: @Brooke4Trib —

Male inmate bed crunch

The Utah Department of Corrections will ask lawmakers next session to approve construction of a $37 million, 192-bed new unit at the Central Utah Correctional Facility in Gunnison.

Mike Haddon, deputy director, said legislators will need to address the request in 2014 in order to have the new facility ready for business by March 2017, when it will run out of room at the state's two prisons and county jails for a growing population of male inmates. The male population is increasing at a rate of nine new inmates per month; the female population is increasing at the rate of two per month.

According to department projections, it will have 6,837 male inmates by 2017.

It takes about 36 months, once funding is approved, to build and open a new unit, Haddon told the Legislature's Executive Appropriations Committee Tuesday. Haddon said the department expects to have $10 million in its nonlapsing fund budget to offset the cost of the new facility, which has been pitched to lawmakers several times in recent years.

In the meantime, the department will increase its contract beds at county jails to alleviate pressure at the prisons in Draper and Gunnison. It will need an additional 120 contract jail beds by next July and similar number by the summer of 2015. This year, it has a budget of nearly $29 million to pay for 1,696 beds at county jails to house state inmates, Haddon said.

Brooke Adams Of note: In Utah, more than one-third of female inmates are serving sentences for property crimes. Another 17 percent committed crimes against persons, while 16 percent are serving time for alcohol and drug offenses, according to the Utah Department of Corrections.