This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In October 1918, Pfc. Walter Herbert Anderson marched with the U.S. Army 91st Division during World War I into what was known as the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

The German army unleashed mustard gas, which blinded Anderson, a native Utahn, for weeks and left him with burning eyes, bronchial problems and nervousness. He died in 1955 of a rare form of melanoma that began in his right eye and metastasized into his brain.

On Friday, his grandson, Bradley Anderson accepted a Purple Heart on his grandfather's behalf, ending a two-year crusade to find enough military records to persuade the U.S. Army to bestow the medal on the man he calls Granddad.

"In my imagination, I never thought this would happen," Anderson said during ceremonies in the Gold Room at the Utah Capitol. "Today, the veil between heaven and earth parted."

Walter Anderson grew up in southern Utah and joined the Army soon after the United States entered the war. He left behind his wife, whom he'd married five months earlier, and became a part of the "Wild West Division."

Like other soldiers who were gassed, Anderson was treated by American medical crews in French homes because they carried "gas residuals" that were active for days. He was not counted among American wounded because his injuries were not considered to be wounds.

Anderson was released from the Army in 1919, returning to his wife and farm. Eventually, however, the family moved to Salt Lake City to find better work, and Anderson would serve as a Salt Lake County commissioner, a clerk in the Utah Legislature and a top leader of the Utah Veterans of Foreign Wars.

When Bradley Anderson launched his quest for his grandfather's records, it seemed unlikely if not impossible. He wondered if the records still existed, given that so many military records had been lost, discarded or accidentally burned over the decades.

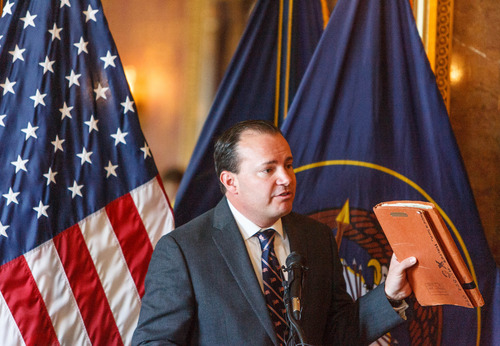

Then he contacted U.S. Sen. Mike Lee, whose staffer, Wendy Johnson, took on the case with a fury. At one point, Anderson was ready to give up, but Johnson wasn't, he said. Finally, she tracked his grandfather's records to Bangor, Maine.

A man there told her, "I'm holding [the folder] right here in my hands." It proved to be a complete collection of his military records, which backed up Walter Anderson's claims about the enduring effects of mustard gas and his efforts to get medical help.

In June, the Anderson family received a letter from the Department of the Army clearing the way for Walter Anderson's Purple Heart.

Just last Monday, Bradley put the medal in his father's hands. He died that day, which was Bradley's birthday.

Bradley Anderson believes that if his grandfather were alive today, he would not accept it "unless he could receive it for all the gas casualties of World War I."

Bradley closed his remarks Friday with a quote from the poet Robert Browning: "Ah, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp, or what's a heaven for?"