This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Strawberry Reservoir • Three young men were lost to Strawberry Reservoir during a 1995 fishing expedition. Todd Bonner dragged lines through the water for two months without any luck.

"There's nothing worse in my mind than closing out a search and you're not able to find that person, especially in the water when you know your family member's in there," said Bonner, now the Wasatch County sheriff. "I've had to do it numerous times."

Then during the cold November of 2006, the state dive team went out to find a drowned married couple, Steven and Catheryn Roundy. After only a week on the water, the team found the couple, two of the three young men and a long-lost swimmer.

The world had changed, thanks to a paradigm-shifting sonar.

—

Better technology >> Searchers once had to tow hooks through the water and rely on radar meant to find fish. When divers did go down, they had to slowly and meticulously feel their way through a dark, disorienting void with no good way to know for certain which patch of lake bottom-turned-graveyard they had searched and which they hadn't.

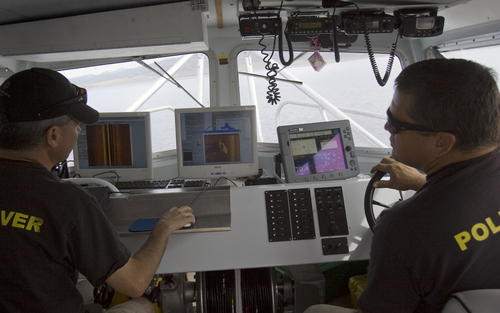

As the state team's boat cuts through the placid waters of the lake during a practice run earlier this month, an orange representation of the world beneath fills the monitor in front of Mike Tueller.

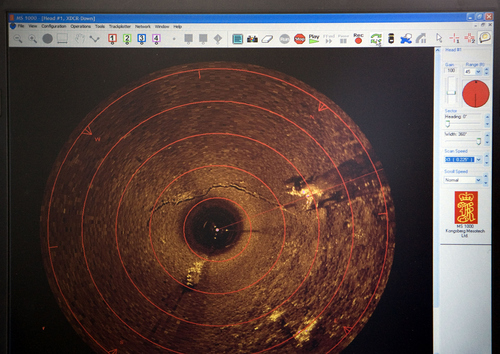

Ancient rocks, grooves and shrubbery scroll down the screen as the boat moves, pulling a sonar several dozen feet beneath the surface of Strawberry Reservoir. Before long, a bright yellow object creeps into the image on the starboard side that Tueller, a Utah Highway Patrol sergeant and long-time member of the state dive team, knows how to interpret: It's the fishing boat that took the three boys with it.

The Utah Department of Public Safety dive team's side-scanning sonar looks like a missile, with a dolphin sticker on one of its fins. Hanging from the front of the boat by a long cord, it turns the dark world below into an easily read map, highlighting details as small as submerged barbed wire lines. The sonar can reach as far as 600 feet on either side of the boat, but the image loses accuracy with distance. Ninety-eight feet is their standard protocol.

Once the team finds the target, they mark it with GPS coordinates and drop a sector scanner — a tripod that scans the water in 360-degree sweeps — to the bottom, allowing those on the boat to direct the divers through the dark water.

The team has a saying that there is as much breathable air underwater as there is on the moon. It's a risk every time a diver goes down. But now they have a mantra: "one dive," Tueller said. Thanks to sonar, that's all it has to take.

—

The team >> The dive team — 10 state officers and a state forensic scientist — formed in 2001, thanks entirely to federal grant money. They drop their regular duties about six to seven times a year to help a county sheriff's office or the National Park Service find evidence ditched in a river or lake or, more commonly, look for a body.

"Cancún is fun diving. This is not fun diving," said Sgt. Wayne Gifford. The dive team is the toughest assignment Gifford has ever had in his 22-year career. But it's also the most rewarding. "It's mind-blowing how good it feels. [The missing] are coming home, and you were a part of that."

After the Roundy couple were recovered, the agencies who helped find them were invited to the funeral. Wendell Nope, a founding member of the dive team who trains new recruits, recalled how a relative had thanked the searchers, then, tearing up in the middle of his speech, simply and silently pointed at the dive team for about 10 seconds. Nope felt like a hero.

"I'm a state police officer. We chose a warrior life, if you will," Nope said. Searching "nasty, dangerous" waters for an adult is unsettling, and a drowned child horrific, but he said that "when there's a child at the bottom of the lake, there's something inside me that says go find that child."

The team does not scour water for the dead for any prestige. There is little glamour for divers to swim through Utah Lake at 1 a.m., the water so dark and murky that they have to hold their compass directly against their mask to read it, blindly reaching for the body of a teenage girl.

"It's a true public service," said team leader Capt. Doug McCleve. "The mission is critical and the service is immeasurable."

When McCleve picks new members, he looks for people who can handle the pressures they face and those who can get along well with the team. The careful selection process has led to a band of close-knit brothers.

He stresses that every recovery is the accomplishment of several agencies working together, including the dive team, who have their limitations. The sonar, for all its advantages, can have trouble with the complicated topography of Lake Powell, which McCleve refers to as "the big leagues." Only other agencies' submarine-like robots can see inside the deep trenches.

His team was out at the lake earlier this summer, when two young women drowned in a boating accident. It took days to find them, but the side-scanning sonar eventually picked up images of their bodies, close together and more than 400 feet down.

—

Inspiration • It still haunts McCleve that the third young man's body is somewhere on the bottom of Strawberry Reservoir. But he is immensely proud of his team.

Everyone has a lake they do not like, be it Flaming Gorge or Bear Lake for their freezing temperatures, Utah Lake for its impenetrability, Lake Powell for its vastness and messy floor. Searching watery graves is a grim job, but as far as the team is concerned, it's their honor to do it.

And the world has taken notice of their quiet efforts.

After the Strawberry Reservoir recoveries, Wasatch County Sheriff Bonner said the phone calls started pouring in from people around the country and Canada who wanted to enlist the state dive team. The team has been to Wyoming and Arizona since then. The International Association of Dive Rescue Specialists honored the team for its Strawberry search with an award given to only one dive team in the world each year.

That search gave several families closure and helped Bonner close a case that he had worked personally. He hopes with the sonar and state team's help, they will close many more: Bonner recently acquired a side-scanning sonar for his department.

Twitter: @mikeypanda