This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

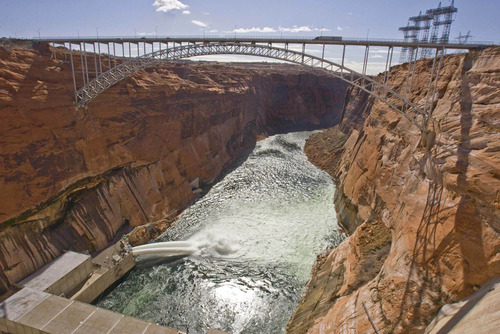

The Colorado River's meager flows and Lake Powell's plunging water line are expected to trigger significant cutbacks in releases from Glen Canyon Dam for the first time in its 47-year history, a prospect that is renewing calls on Utah and other upper basin states to shelve diversion projects and has Las Vegas talking about seeking federal disaster relief.

July's actual flow into the reservoir separating the Colorado River's upper and lower basin turned out be about 100,000 acre feet less than forecast, or 13 percent of July's normal inflows, according to Michelle Stokes, of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

"That was the huge shocker. The month before was 35 percent of normal," said Stokes, the hydrologist in charge of NOAA's Colorado Basin River Forecast Center. And the outlook for the next several months is not much better.

It is widely expected that this new data will prompt the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to reduce Glen Canyon releases next year by 750,000 acre feet, enough water to supply 1.5 million homes.

"We had very low years the past two years, almost record lows for the upper basin," Stokes said. "We are starting with relatively dry soils and low flows. Our forecast is for below normal, 80 percent. We are thinking 33 percent in August and 44 percent in September, 60 to 70 in October."

Stokes' Salt Lake City center gathers and processes precipitation and flow data Reclamation uses to guide monthly updates to its 24-month study that predicts water availability in the Colorado, an overtaxed source for 30 million Westerners. The latest installment is expected to be released Friday.

The scenario water watchers fear is one in which Lake Powell's level dips below 3,575 feet above sea level, which appears increasingly inevitable. Under a 2007 accord between the river's upper and lower basins, this is the threshold where annual releases would be trimmed from 8.23 million acre feet to 7.48 million. As of Wednesday, the level was 3,592 and dropping by two or three inches a day.

Also at stake is the safety of Glen Canyon Dam's power generators, whose conduits open at 3,485 feet. Should the lake level fall to 3,520 feet above sea level, vortex action could damage the turbine blades.

Cutting back releases would be a historic move, one that should spark a paradigm shift in how the West manages and thinks about the river, said Gary Wockner, campaign director for Save the Colorado.

"The future is here and we need to change the conversation now," Wockner said. "Conservation, efficiency, and regional recycling have to be catapulted to the front."

His and other groups are citing Powell and Lake Mead's plunging levels to promote the "Fill Mead First" proposal and urge Utah to abandon proposed diversions that would feed a nuclear plant and a pipeline to St. George. Both reservoirs are just under half their capacity and more than 100 feet below full pool.

"The bottom line, there is no water left in the system. If anybody takes more water out, someone else is going to have to cut back downstream," Wockner said. "We have a scientific and ethical responsibility to consider every option in this crisis."

Lake Powell is valued as a boating destination and source of hydropower, but was not built with a water storage role, Wockner said. The Glen Canyon Institute says maintaining Lake Powell costs up to 1 million acre feet annually through evaporation and ground seepage. That's nearly 7 percent of the river's flow in a normal year.

The downstream user with the most at stake is Las Vegas, which relies on Lake Mead for 90 percent of its water.

Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) chief Pat Mulroy has floated the idea of seeking federal disaster aid if Lake Mead continues to shrink, telling the Las Vegas Review-Journal last week she thinks damage to the region could compare with Hurricane Sandy's impact on the East Coast last year.

Filling Mead at the expense of Powell might have some short-term benefits, but it would not result in more water availability, according to John Entsminger, SNWA's senior deputy general manager. This is because the reservoir impounded by Hoover Dam sits more than 2,500 feet lower than Powell, where temperatures are hotter and evaporation losses would be greater.

However, the anticipated cutbacks in Glen Canyon releases would lower Mead's level an additional eight to 10 feet, hastening the day when the upper of Las Vegas' two intakes will begin sucking air, Entsminger said. This could happen as early as spring 2015, not long after the city's costly third straw drawing water from Mead is scheduled to be completed.

"This is uncharted territory. We aren't sure when we lose operational capacity [of the upper intake]," Entsminger said. "For the next 24 months we need to determine the immediate actions on the river to secure the water supply."

SNWA's leadership says the crisis on the Colorado is not just a problem for Vegas, but a regional issue with implications for the national economy since the river helps feed one-fourth of the gross domestic product. A lasting solution can only come about if the seven basin states work together, Enstminger said.