This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

For two decades, Melanie Stringer has been in and out of jails and institutions.

Nothing has worked to keep her from making bad decisions and getting locked up over and over and over — not losing her freedom, not a host of voluntary and required life-skills classes or rehabilitation programs.

"I'd think I was OK," says Stringer, 51, "but I was still walking out with shame and guilt."

So here she is again, midway through her fifth stint in state custody.

But this time, Stringer says she has found the key to leaving prison behind her for good. It's called Getting Out by Going In (GOGI), a set of 12 positive decision-making tools that Stringer and thousands of inmates across the country say is — finally, forever — changing their lives.

"It is not just another life-skills class," says Stringer as she sits in a library/meeting room at the Wasatch County Jail. "It is my life. It saved my life.

"For the first time," she adds, "I'm not afraid to walk out these doors."

—

By inmates, for inmates • Mara Leigh Taylor, the founder of GOGI, says the inspiration for it came from male inmates she worked with as a volunteer at the Terminal Island federal prison in San Pedro, Calif., in 2002.

As Taylor, who lives in California, listened to inmates talk about their lives, their coping and survival skills, she discovered they had their own set of "magical tools" for modifying their behavior.

One inmate told her that if a person wanted to get out of prison, he had to go on an inward journey. Another inmate told her he had learned he could be the boss of his own brain — a phrase that would become the first GOGI tool.

For a decade, Taylor continued to work with men and women inmates to come up with a "complete life-changing package," the 12 tools of GOGI available in a book, workbook, training and certification guide distributed by her nonprofit organization.

Taylor is the first to acknowledge the concepts underlying GOGI aren't new; they parallel proven psychological and behavioral theories, and ideas used in many rehab programs. What sets GOGI apart is its by-prisoners, for-prisoners approach.

"Every tool, the name of my company, my title, came from prisoners," says Taylor, who has two master's degrees in psychology. "Every single word printed in the book is the voice of prisoners."

Today, Taylor says, GOGI students are in prisons and jails in every state. Some read the book, newly revised in January, on their own; others form groups that work together to implement the tools; and some are led by volunteer coaches. There also are GOGI groups in treatment centers, halfway homes and support groups organized by ex-cons.

Jim Bristow, who works with inmates at the Wasatch County Jail, came across GOGI about four years ago when he was looking for better material for a life-skills class. In 2009, the jail set up a 90-day GOGI therapeutic community for female inmates.

Word spread as other law officers heard about the program and as inmates moved from jail to prison.

"These 12 tools are getting people back in control of their lives," Bristow said. "During a class you can sometimes see the light bulb go on. It doesn't happen every week, but enough to keep me going."

—

'I can' • Once a week, about 30 male inmates at Salt Lake County's Oxbow Jail gather at 10 p.m. for what's called the "Graveyard GOGI" class.

The jail introduced GOGI in a life-skills class a few years ago; it caught on, and today inmates run the GOGI classes, including the late-evening sessions and a new Spanish-language group.

"There are some of these guys in here I've seen coming in for a decade or so, and I can see changes," says Sgt. David Wilbur, who supervises the Graveyard GOGI class. "A lot of the reason is because they feel that sense of ownership. It is not something they are coming in solely to learn from us, but with the understanding they are going to teach it to each other."

On a recent night, three inmates are running the GOGI class. They open by chanting the 12 GOGI tools in unison before Angel Balderrama, 36, asks if anyone has a poem he'd like to share.

John P. Stickney, 39, goes first and shares a verse he wrote called, "Teach Me How to GOGI."

The evening's class is focused on positive thoughts, words and actions, three other GOGI tools. As other inmates at the jail bed down for the night, these men, clad in navy blue jumpsuits and fluorescent orange shoes, watch a series of video clips of actor Will Smith talking about making positive choices in life.

Balderrama then asks the men to share examples of positive things they think about. From around the room, men call out answers: Family. Wife. Kids. Health. I can. I'm a good person.

Taaloga "Tony" Aiono, 34, and Tevita Niu, 33, take over, pushing for examples of positive words.

From around the room, men again call out answers: I can. I am. I will. Great. Success. Grateful.

"These are good words, guys," Aiono says.

Aiono and Niu then offer examples of positive actions undertaken by their fellow inmates — one man's word-a-day dictionary study habit, a focus on working out, reading scriptures, being polite and making eye contact with people.

"How many of you guys are leaving the negative in the dust?" Niu asks.

All hands go up.

—

The GOGI way • Taylor stops short of calling GOGI a "program," instead describing it as a "culture" and a "new way of doing prison time that allows a person to improve on their own and allows them to do it without tax dollars or having to be on wait lists for programs."

She self-publishes GOGI materials, which inmates may buy or have donated to them, to keep costs down and preserve the foundation's ability to give them away for free.

The interest from inmates in Utah is "insatiable," Taylor says, but getting GOGI books into their hands has been a challenge.

At the Gunnison prison, there are 250 men who want to participate but can't afford to buy the book; instead, those inmates made copies of a couple of books paid for by a California donor and shared them, Taylor says.

"It's the least-expensive way to empower them to make positive decisions," Taylor says. "There's not any other way that has the effectiveness at the low cost that GOGI is providing."

Steve Gehrke, spokesman for the Utah Department of Corrections, says there is a "minimal level of support" for GOGI at the prison.

"It's fair to say it gives [inmates] some intangible coping mechanisms and ways to calm themselves," Gehrke says, "but from our perspective we haven't seen any evidence-based support that it helps reduce recidivism."

In Utah, the recidivism rate is about 54 percent; 67 percent of all prison admissions annually are people who violated parole conditions.

Taylor says a study by the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department found that GOGI dropped recidivism from 85 percent to 35 percent among female inmates who participated in its all-volunteer, donor-funded therapeutic community program. Taylor acknowledges more studies are needed to validate GOGI's impact and is inviting academics to study the program.

"The [Utah] system is designed to require evidence-based and statistical evidence that anything works," Taylor said. "So they rely on programs designed with well-meaning people to serve this population. The problem is that has never worked with this population. The only thing that is going to work is giving them tools they never had to make positive decisions and allowing them to make changes themselves."

All we have to prove the effectiveness of GOGI, Taylor adds, are "thousands of people writing to say these tools work."

—

Need ongoing support • There are 31 women crammed into the meeting room at the Timpanogos Women's Facility at the Utah State Prison in Draper as part of a 12-week GOGI class. Volunteer Lynn Whipple is leading them through a belly-breathing exercise. It's tool No. 2 in the GOGI kit, designed for use in moments when one needs to slow down, not act impulsively or out of anger, and think clearly. Eyes are closed; some women have a hand over their hearts.

"This moment, this here, this now is really all you have control of," Whipple says. "This is what your now and your future can be like."

These women, like the inmates at Oxbow, are discussing the relationship among positive thoughts, words and actions.

"It's still just book learning until you practice what you preach," says volunteer Roark Stratton, who team-teaches the class with Whipple.

It's a concept that resonates with Darryll Peterson, 43, who has been locked up for the 10th time.

"I know they don't trust me," she says of her family. "I made a lot of promises that were empty."

Tangie Anderson, 31, faces the same challenge.

"This time around, my son has told me, 'I don't want to hear you're going to get out and change,' " she says. "I've got to show him."

One hurdle is believing in themselves, they agree. Another is letting go of the past.

"If the past is still with you and you can't let it go, it's not the past," Whipple says. "It's still the present."

A week later, Peterson gets a chance to put the GOGI tools into practice when she appears before the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole.

"I do have these tools, and I just need to continue to implement them," Peterson tells the hearing officer. "I need to be aware of abusive relationships and allowing myself to be sucked into self-defeating and self-damaging thoughts and behaviors. And I think I am learning more of that really with the GOGI. The tools they have in that are really effective, and I use them every single day in my daily life."

Taylor says GOGI works on two levels: It increases compliance and likelihood of success in prison, as well as once an offender is back in the community.

GOGI works because "it is something [inmates] feel is real because it was created by people in their situation and who got out of their situation," says Eileen Beales, Corrections deputy over the Wasatch County Jail's GOGI tier. "They are rewriting who they are and getting rid of old labels, which is important because [those labels] have been negative for years. Negative labels are stripped away and positive tools are given to them, which possibly they never had before."

But there is a need for ongoing support, which is why Taylor is trying to seed interest in GOGI among groups that work with offenders once they are released. In a visit earlier this year to southern Utah, Taylor presented the GOGI approach to probation officers and staff at a homeless shelter, a re-entry thrift shop and a Deseret Industries store.

It is already happening in Salt Lake County. Niu and Stickney, who were released from the Oxbow Jail in the past month, are helping Salt Lake City's Adult Probation & Parole office set up a GOGI class for female parolees and probationers.

—

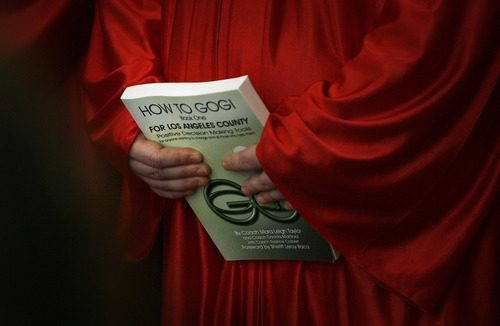

What if? • There is loud and long applause as nine women in red graduation gowns and matching mortarboards file into the library/meeting room at the Wasatch County Jail.

There's Gaige Devlin, 22, who has been on what she calls a "hard road" since she was 13. And Laveryl "Sugar" Mortensen, 43, who vows to share the GOGI book — the first book she's ever read — in her small Utah hometown when she's released in a few weeks. And, yes, Melanie Stringer is graduating from the program, too.

Jared Rigby, chief deputy for the Wasatch County Sheriff's Office, tells the women that everyone gets a shot at a life-changing experience at one point or another.

"It can turn out for the good or for the bad," he says. "It is up to us how it turns out. Today, for you, there is a decision: Am I going to make this more than temporary? Am I going to make this permanent? Will I be able to look back and say, 'This is where it all began?' "

This is where the "what if" tool that GOGI preaches comes in.

What if these women became the mothers their children deserved? What if they did a little belly breathing next time a bad habit resurfaced and just turned away? What if they dared to become the powerful women the world needs?

Hopes are high.

"I've been doing time for 15 years and never felt like I could conquer my addictions," Angela Delgado, 35, tells law officers and volunteers in the audience. "GOGI taught me to dream again."

brooke@sltrib.comTwitter: Brooke4Trib The GOGI Way

Getting Out by Going In is a positive decision-making guide based on 12 tools drawn from experiences of thousands of inmates. To volunteer as a coach call 801-940-7440.

1. Boss of My Brain • Control your brain or let others do it. You can be a good boss or a bad boss.

2. Belly Breathing • Use deep breathing to calm body and mind and counteract impulsive, angry reactions.

3. Five-Second Light Switch • Replace old, automatic thoughts with new, positive actions.

4. Positive Thoughts • Replace negative thoughts with positive ones.

5. Positive Words • Your positive words tell the world who you are. Use positive words to improve all areas of life.

6. Positive Actions • Choose actions that enhance your life and lead to positive change.

7. Let Go • If you let go of the little stuff, the big stuff often disappears, too.

8. For Give • It's less about the spiritual concept and more about getting distance from harm or harmful people "for" you to "give" back.

9. Claim Responsibility • In the GOGI way, this is a tool for making good decisions that create a good future.

10. What If • It's a way to see how one positive choice leads to another and imagine a new, different life.

11. Reality Check • Acceptance of imperfection and acknowledgment that change is a process. Backsliding may occur, but you are still moving forward.

12. Ultimate Freedom • You are able to be of service and do good — the only true freedom without any expectation of recognition and regardless of others' actions.

Source: Drawn from "How to GOGI" Teach me how to GOGIThat's what people saySo listen upAnd I just mayFirst things to remember I'm boss of my brain My choices are all mine, And that's always the same.

— Excerpt from "Teach Me How to GOGI," a poem by John P. Stickney, a former inmate at the Oxbow Jail in Salt Lake County