This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Brian Scott endured six grueling months of chemotherapy in 2012 only to see his acute myeloid leukemia, a fast-growing cancer of the blood, return.

The St. George man was admitted this summer to Primary Children's Medical Center for a second, more intensive infusion of toxic chemicals in preparation for a stem cell transplant. This time, the treatments nearly killed him.

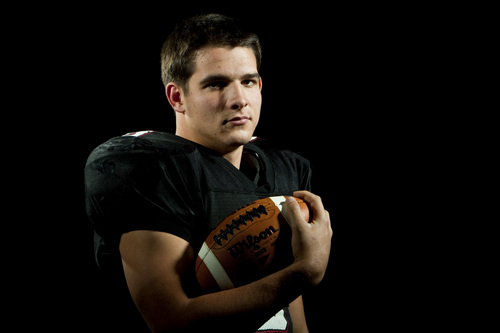

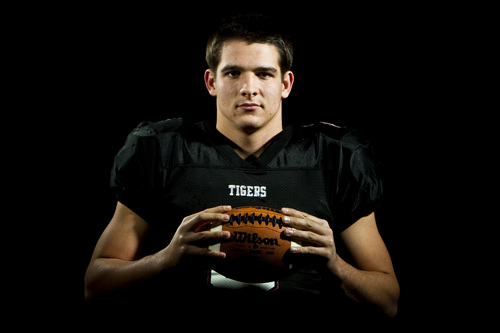

The 225-pound fullback, who carried the Hurricane Tigers to their first state championship, captured three state wrestling crowns and won a Southern Utah University football scholarship, called it quits on chemo. Brian, now 20, moved to Colorado this summer for an alternative treatment: medical marijuana.

"This is not just about kids. Adults need it, too, and not just for nausea and pain," said Brian's mom, Jane Scott, referring to the push by a group of Utah moms to import a cannabis extract for their children with epilepsy.

The extract comes from a plant, cultivated by the nonprofit Realm of Caring Foundation in Colorado Springs, that is high in cannabidiol (CBD) but low in tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive chemical component that creates a high in users. It's so low in THC that, Utah parents argue, it meets agricultural standards for hemp used in clothing and lotions.

They make their pitch Tuesday to the state's Controlled Substance Advisory Committee, a group of doctors, cops and prosecutors that advises lawmakers on the scheduling of drugs.

Because there's a growing waiting list for the low-THC extract, Realm of Caring reserves it for children. Brian uses another Realm product with a slightly lower CBD to THC ratio.

"Death is a possibility with or without the chemo," Jane said, "and we all decided if he lives, he will have a life and won't just be fighting a disease for years on end."

—

'Spitting blood' • Brian was diagnosed at 18, weeks before he was scheduled to leave on a mission for the LDS Church to Uruguay. He was optimistic during his first round of chemotherapy in 2012 and fully intended to take advantage of his SUU scholarship, his mother said.

The cancer returned three months into his remission, and he started a second round of chemo this summer.

"The chemo attacks all the rapidly growing cells in your body, including your hair and the cells lining your mouth and esophagus, which became raw and infected the second time around," Jane said. "He was spitting blood and couldn't eat or drink and had to be kept on IV fluids for several weeks."

The transplant doctor wanted Brian to resume chemotherapy when he was strong enough and said, "I can give you five times what you're getting now," recalled Jane.

Brian, then 19, said, "No."

Doctors had already downgraded his five-year survival odds from 80 to 50 percent. "He just felt like his body wouldn't live through it," Jane said.

Doing Internet research, she found studies on the cancer-arresting properties of compounds in marijuana known as cannabinoids. She watched a video by another Utah mom who had moved to Colorado Springs from Kanab to get cannabis oil for her son with leukemia.

On the July day the Scotts resolved they would make the same move, they received grave news from Luke Maese in the hematology and oncology department at Primary Children's, the doctor closest to Brian.

The cancer, untraceable after the last round of his interrupted chemo, was back.

"We had already told him we weren't going the transplant route," Jane wrote on a blog she kept of their experience, "to which he replied to Brian in all sincerity, 'You're going to die!' "

Within weeks, Brian was settled in Colorado and taking cannabis pills from the Realm of Caring.

—

Research needed • Mounting evidence of marijuana's therapeutic benefits has spurred powerful doctor lobbies — the American Medical Association and American College of Physicians — to press for its reclassification.

While neither group endorses state-based cannabis programs, they are calling for more research, which some say is stymied by federal restrictions.

Doing clinical research with marijuana requires approval from the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), said Igor Grant, director of the Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research at the University of California, San Diego.

"It's burdensome and time-consuming. ... Not everyone has the financial resources for that," he said.

Grant's center has completed more than a dozen studies documenting the therapeutic benefits of marijuana for controlling nausea, treating some kinds of pain and muscle spasms, and stimulating appetite.

Lab studies on its anti-tumor effects beg further exploration, he said. "But I'm not yet persuaded it's a viable cancer treatment. ... It's one thing to observe something in cell preparations and quite another to say it does the same thing in organisms or people."

—

Compassionate use • Glen Hanson, a pharmacology and toxicology professor at the University of Utah and a senior adviser to NIDA, sits on the advisory group hearing the cannabis plea on Tuesday. He is not open to a wholesale legalization of medical marijuana or re-scheduling it.

But he's not opposed to making it available to a limited number of patients, under a doctor's orders in a compassionate use program.

"If you have HIV/AIDS and cancer and it helps alleviate your pain and nausea so you can eat, sure, let's give it to them and provide some relief," he said.

Cannabinoids have long been shown to have anti-seizure properties, and patients, even children, for whom there are no alternative therapies might be good candidates for the drug, he said.

But broadly legalizing marijuana puts hordes of others at risk, including young people who might be more inclined to try it and who can suffer irreparable damage to their still-developing frontal lobes, he said.

"It would be like saying, 'Let's smoke cigarettes because it prevents Parkinson's disease,' " he said, referring to studies showing smokers are less likely to have the disease. "Smoking kills 400,000 people a year and is very addicting."

Even if Utah were to create a compassionate-use program, it may be difficult to find doctors willing to prescribe it.

"Until recently all you ever heard is it's a dangerous drug. Also there are no clinical trials and very little published evidence, which puts docs in a tight spot," said Margaret Gedde, a Stanford-educated Colorado Springs pathologist.

She notes that in Colorado, health insurers and malpractice underwriters have threatened to pull coverage from doctors who recommend it. "It's just so far out of normal practice."

—

Holding onto hope • In August, Brian was exercising again, eager to mountain bike and resume football training, his mother said.

"When we left Utah tests showed there were was 3 percent blasts, or immature cancer cells, in his blood. Subsequent [blood counts] have not shown any blasts," Jane said on Aug. 27. "Now the hope is his body starts reproducing the healthy cells."

She urged Brian to "hang in there" and stay in Colorado for at least six months. "Because of Utah's marijuana laws we can't legally go home because we could get hit with a $1,000 fine and three months in prison," she said.

Shortly after Brian's 20th birthday in September, though, cancer cells reappeared. He began low doses of chemotherapy while continuing to take cannabidiol pills.

Brian remains steadfast in his refusal of a stem cell transplant.

"He knows what that hospital routine is like. He feels like if he's going to go out of this world, he is going to go out fighting and not so doped up on morphine he can't tell one side of the veil from the other," Jane said.

She tries to stay positive but says state and federal laws need to change to grant families access and allow for more research.

"If it wasn't illegal and we could properly study this, we could have so many advantages. But it's been suppressed for so many years that there haven't been adequate clinical trials," she said. "I'm frustrated scientists didn't explore this earlier." —

Join us for a Trib Talk

Today at 12:15 p.m., reporter Kirsten Stewart, marijuana grower Josh Stanley and others join Jennifer Napier-Pearce to discuss Colorado's experience with medical refugees.

You can join the discussion by sending questions and comments using the hashtag #TribTalk on Twitter and Google+. —

Marijuana history

Cannabis is a 38-million-year-old plant, one of humankind's oldest cultivated crops that has been used medicinally since at least 2800 BCE, writes Julie Holland, an MD, in "The Pot Book: a Complete Guide to Cannabis."

"In America cannabis was a patent medicine, an ingredient in numerous tinctures and extracts throughout the 1800s and early 1900s," Holland writes.

But concerns about its recreational use gave rise to a series of legal restrictions, starting with the Marihuana Tax Stamp Act in the 1937 and culminating with the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, which classified marijuana as a Schedule I drug alongside heroin and LSD, deeming it to have no medicinal value and a high potential for abuse.