This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

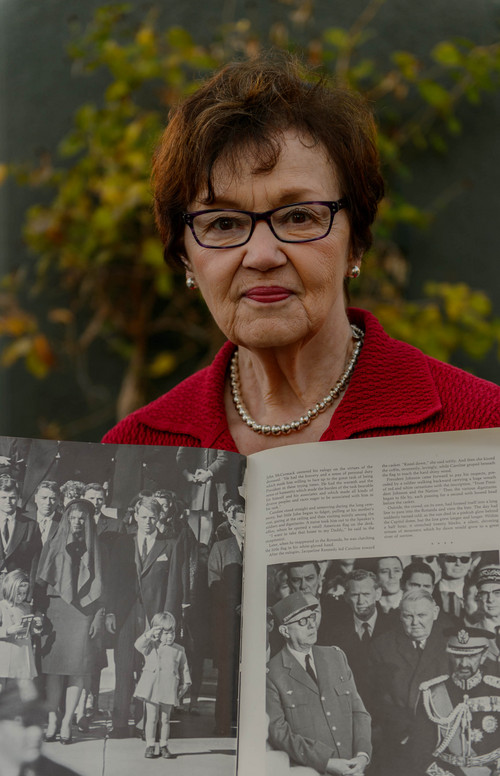

Fifty years later, Rosemary Baron still remembers where, when and how she learned the awful news about John F. Kennedy — the nation's first and only Catholic president.

"We were just changing classes and the president of our college came through the halls," said Baron, then a student at Mary Manse College, a Catholic institution, in Toledo, Ohio. "I said, 'You sure don't look like yourself.' She said, 'Our president has just been shot.' "

Kennedy's assassination remains a collective memory, one etched forever by shock and grief in the minds of Americans who heard the news Nov. 22, 1963, of the fatal attack on their young, vibrant leader.

Just 55 days earlier, Kennedy had visited Utah, where he was welcomed by more than 100,000 residents along a parade route in Salt Lake City. He gave a speech at the LDS Tabernacle that centered on the dangers of isolationism while invoking images of the Mormon pioneers as exemplars of America's best qualities: courage, patience, faith, self-reliance, perseverance and "above all, an unflagging determination to see the right prevail."

But that fall day Utahns, like the rest of the country and the world, were sent reeling.

Six Clearfield High students touring The Salt Lake Tribune's newsroom were standing next to the teletype machine as the first bulletin reporting the Texas shooting came across the wire.

Gerry Callahan, then in 12th grade, was attending an assembly at Judge Memorial Catholic High School in Salt Lake City. Like Baron's, Callahan's reaction to the news went beyond his faith connection to Kennedy.

"I remember the principal ... stepping out and interrupting the assembly and announcing John Kennedy had been shot," said Callahan, now 66 and a professor of pathology and English at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. "I remember, for the first time, feeling a lot more vulnerable than I had felt as a U.S. citizen before that. For the first time, I felt this was a very different world than I imagined it to be."

When Kennedy's death was confirmed, state offices closed. Salt Lake City schools let out early. People grouped around television sets and radios for the latest updates. An estimated 1,000 callers swamped The Tribune's telephone switchboard, asking in "obvious disbelief" whether the news was true.

And the bells at the Cathedral of the Madeleine tolled for 15 minutes.

Leap of faith • Kennedy's election three years earlier was seen as a game changer as the nation bridged a religious, psychological and cultural chasm, smoothing the way for future minority candidates and causes.

"It is hard for people to realize how much anti-Catholic sentiment there was in the United States, even as late as 1960," said Michael Lyons, associate professor political science at Utah State University. "There was a level of excitement and drama about this for Catholic Americans and, I think, also for the black community, who turned out heavily [for Kennedy]."

The Massachusetts senator solicited support of African-American voters, Lyons explained, by asserting that the election of the first Catholic commander in chief could help propel the political advancement of all minorities.

"It was a tremendously important landmark, in my view," Lyons said, "and because the fears of anti-Catholic voters were not realized and because Kennedy was such a charismatic president, it is easy to forget how horribly controversial the idea of a Catholic president was and how it divided the country."

Kennedy confronted the issue head-on in a historic speech Sept. 12, 1960, to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association, a group comprised of Protestant ministers.

Protestants in particular had questioned whether Kennedy would be able to act independently of his church — the same question posed more recently, if less vociferously, to Mitt Romney, a member of the Utah-based Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, during his two failed presidential bids.

Kennedy first listed the core issues at the heart of the 1960 election: communism's spread, war, hunger, despair, poverty, aging, access to health care and the country's failure to keep up in the space race. Those issues, he conceded, had been overshadowed by questions about his faith and now forced him to "state once again not what kind of church I believe in — for that should be important only to me — but what kind of America I believe in."

"I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute, where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote," Kennedy said. "Where no church or church school is granted any public funds or political preference; and where no man is denied public office merely because his religion differs from the president who might appoint him or the people who might elect him."

He believed, Kennedy said, in an America where there was no religious intolerance.

"I am not the Catholic candidate for president," he said. "I am the Democratic Party's candidate for president, who happens also to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my church on public matters, and the church does not speak for me."

Mitt's moment • Romney echoed those words in 2007, when he delivered a speech on faith at the George Bush Presidential Library in College Station, Texas. Romney directly invoked Kennedy, "another candidate from Massachusetts."

"Like him, I am an American running for president," Romney said. "I do not define my candidacy by my religion. A person should not be elected because of his faith nor should he be rejected because of his faith."

Five years later, the former governor of Massachusetts became the first Mormon to head a major party ticket. When he picked U.S. Rep. Paul Ryan, a Catholic, to be his running mate, reported USA Today, the two formed the first Republican ticket without a Protestant in more than 150 years.

Protestant numbers are slipping across the nation, according to Pew Research Center polling, but, at 48 percent, they still represent by far the largest chunk of the nation's Christians. Catholics account for about 22 percent.

In the 1960 race against then-Vice President Richard Nixon, Kennedy locked up 78 percent of the Catholic vote — a significant upswing in support for a Democratic candidate. In 1956, the party's presidential nominee, Adlai Stevenson, netted 51 percent of the Catholic vote.

The election of a president who shared their faith "was a momentous achievement for a group that had a much higher level of minority self-consciousness than Catholic voters have today," Lyons said, a "very important threshold point."

Callahan was in ninth grade and remembers how on Election Day "the nuns were all atwitter that a Catholic had been elected when people said that was impossible. It's sort of like it's one of your own, one of my team who got the top prize, that kind of thing."

Kennedy's presidency sharpened Callahan's idealism. But his death set in motion doubts about America that only deepened with the political assassinations and war that followed.

Dee Rowland, then a young mother living in Cheyenne, Wyo., viewed Kennedy's election no so much as a religious triumph but as a hopeful signal that the nation was now sophisticated enough "that someone that diverse could be president, that we had gotten beyond some prejudices."

Then came Dallas.

Policies over piety • Rowland, sitting down to feed her baby, had a radio tuned to a classical station when the news flash interrupted the program. She and a neighbor spent the rest of the afternoon listening to updates.

"It seemed like something that happened in past history and couldn't happen in that day and age," said Rowland, former government liaison for the Catholic Diocese of Salt Lake City. "It was so stunning."

Three days after the shooting, as the 35th president was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery, Mormon apostle Harold B. Lee, captured the mood of the country and the spirit of the slain leader with this remark:

"A nation in mourning is something to evidence," Lee said. "There is but one heart, and it is indeed heavy and sad. There are no party lines in the country today. There is no creed. There is no color. There are no poor and no wealthy. All weep unashamedly together. We mourn as a national family."

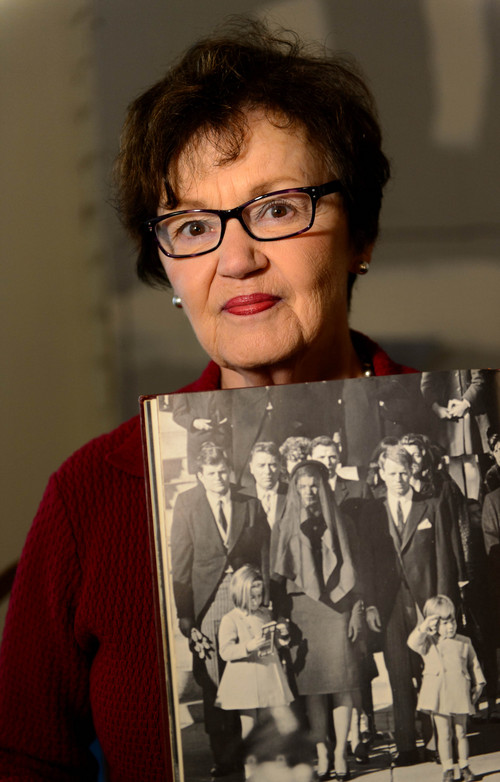

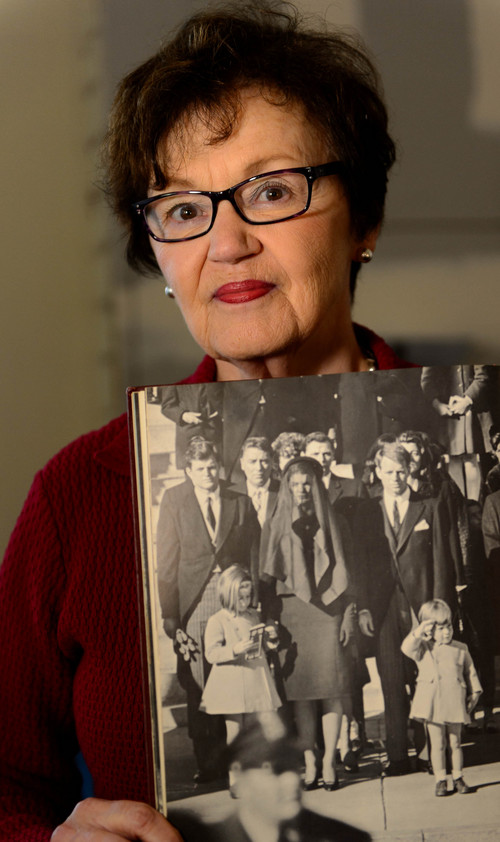

Callahan remembers Judge Memorial canceling classes and students gathering at the school instead to watch the funeral on television. Among the indelible moments: the horse-drawn caisson carrying Kennedy's flag-draped casket to the cemetery; Jacqueline Kennedy, the president's wife, gracefully grasping the hands of their children, Caroline and John Jr.; Kennedy's tiny son saluting his father's coffin.

Kennedy paved the way, in Lyons' view, for a Romney candidacy focused on policy, not piety. It was not the landmark that Barack Obama achieved in 2008, he added, but "it's of almost equal significance."

Back then, though, some who shared Kennedy's religious roots identified with him more because of his progressive views.

"I was young, I was optimistic, I was hopeful," said Baron, 70, who moved to Utah 34 years ago and is a retired school principal. "I loved him. I admired him not just because he was Catholic and I was also, but because he brought hope and optimism to our nation."

What drew her to the president was his "youthful presence and invigorating way of inspiring people," Baron said, especially with his vision for a future when equal rights and civil rights were givens.

"Civil rights were at the forefront of what he had done and the work he was doing," she said. And, yes, Kennedy left an imprint on her own career.

During her 43 years as an educator, Baron was "always cognizant of the civil rights of people. My work, particularly in the Salt Lake area, was recognizing students from low-income and refugee families, always looking for ways we could better address their needs in public education."

As Kennedy strived to show, those are issues important enough to unite a country with a tapestry of creeds — Catholic, Protestant, Buddhist, Baptist, Muslim, Mormon, believer and nonbeliever.

Twitter: @Brooke4Trib